The patient presenting with non-dental orofacial pain can be one of the most challenging aspects of primary dental care and appears to be more prevalent than previously thought. Although a small part of everyday dentistry, dentists are often the first point of call for patients with orofacial pain, usually before the GP, and pain consultations can be among the most difficult to manage.

Time constraints and lack of experience in managing non-dental pain disorders are just some of the challenges faced, but a good history, along with a few simple investigations, can improve the consultation outcome, therapeutic options and, where needed, the quality of pain referrals. This article aims to help clarify some of the most common orofacial pain disorders and, where appropriate, give guidance on investigations and treatment that may be carried on in a primary care setting.

Before considering the following diagnoses, other dental and pathological sources of pain must be excluded through appropriate clinical examination and imaging. The more common non-dental orofacial pain conditions that may present to the dentist include:

- TMD

- Burning Mouth Syndrome

- Sinusitis

- Trigeminal neuralgia.

The acronym SOCRATES (Site, Onset, Character, Radiation, Associated Factors, Timing, Exacerbating/Relieving Factors and Severity) is a standardised tool for pain history and assessment endorsed by many medical and dental schools across the UK and provides a thorough and logical approach to history taking. This is as applicable to the dental practice setting as to the specialist pain clinic. Each of these features should be asked about and the response noted. Remember that the ‘absence’ of a finding can be as important as a ‘positive’ response where pain and its associated

features are concerned – both must be recorded in the notes.

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD)

Background

This is the most frequently seen non-dental pain condition presenting to the dentist. It is also one of the most varied orofacial pain disorders as it can appear in many different ways. Always consider TMD in the differential diagnosis of orofacial pain, even if the symptoms do not seem exactly to fit. This is particularly the case where the pain reported is bilateral. It is easy for the practitioner to treat in primary care and will respond promptly to the correct treatments.

Remember that for TMD:

- Clicking of the jaw in the absence of pain and locking does not require referral or treatment

- Bite splints DO work and should be tried where TMD cannot be excluded. These are now available on the NHS without prior approval. They are not effective alone for every patient, but are used together with other medical and physical therapies to good effect.

Where locking of the TMJ is the main problem, the issue is usually related to the joint itself and these patients should be referred to the local maxillofacial surgery service for assessment.

Aetiology

Parafunctional habits, such as clenching and grinding, are frequently seen in patients with TMD, although many patients also have similar habits without problems. Where pain is present, habits such as chewing gum seem to be an important trigger of pain. Unilateral chewing especially appears to be a risk factor.

Evidence of clenching can be seen from the oral soft tissues with crenulation of the tongue edge and a buccal mucosa occlusal line being common findings. Stress and emotional burden are very often cited, but will not always feature in the history unless specifically asked about by the dentist.

Figure 1

| SOCRATES in TMD | |

|---|---|

| SITE | TMJ, ears, cheeks, temple, teeth, sublingual region Unilateral or Bilateral |

| ONSET | Acute: This is less common. May be following trauma to joint/face, joint dislocation, or muscle spasm.. Chronic: Gradual onset- weeks/ months |

| CHARACTER | Dull ache Throbbing Sharp (with wide opening/ muscle spasm). Less common N.B. Pain is not pulsatile |

| RADIATION | Neck, head (headache), face, upper and lower jaws |

| ASSOCIATED FACTORS | Trismus Clicking or crepitus in TMJ (more common in older age group) Mandibular fatigue and stiffness of the jaw Extra-oral swelling caused by muscle hypertrophy Soft tissue features: linea alba and tongue scalloping |

| TIMING | Morning, during night, during stressful activities e.g. driving |

| EXACERBATING/ RELIEVING FACTORS | Chewing Yawning Playing a wind musical instrument |

| SEVERITY | Range: mild to severe |

Occlusal factors themselves seem to play a very small role in chronic TMD, although

acute changes may be found after placement of a restoration that disrupts the normal intercuspal position. However, looking at the occlusion for triggers in chronic TMD is rarely helpful and often results in destruction of dental hard tissue unnecessarily. TMD itself may in fact cause occlusal changes, as pain-induced muscle dysfunction around the joint results in altered closing patterns of the mandible and a secondary occlusal change.

There is certainly no link with orthodontics in either the origin or resolution of TMJ dysfunctions. Hypermobility of the joints, however, does show an increased probability of developing problems. This is demonstrated in studies on patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, where all patients in the study experienced TMD and multiple joint dislocations.

Who is affected?

As a condition which affects 5-12 per cent of the population, these patients frequently present in dental practice. More women than men are affected by the disorder (quoted up to 4:15) and unlike other types of orofacial pain, its prevalence is higher in a younger age group, with up to 7 per cent of 12-18 year olds diagnosed with mandibular pain dysfunction. However, children and older adults are also affected, commonly with stressful life events being key precipitators.

Interestingly, women taking oral contraceptives or on supplemental oestrogen are also more likely to both suffer from TMD and to seek treatment for the condition. This is thought to be due to the presence of oestrogen receptors in the TM joints, which modify metabolic activity, affecting ligament laxity and also due to the effects of oestrogen on pain experience. There appears to be no genetic predisposition and no influence from the family environment, although many patients citing ‘stress’ as a trigger have home issues!

Examination

Palpate the muscles of mastication for evidence of pain or hypertrophy. Use forced movements of the mandible against pressure to look for pain in the medial and lateral pterygoid muscles. Palpate the TMJs in static and dynamic movements – this may elicit pain, clicking and crepitus, all of which should be noted. Measure mouth opening inter-incisally – as a single measure, this does not contribute much, but can be measured serially to look for improvements as treatment progresses.

Soft tissue features, including evidence of parafunctional clenching and tooth wear, should also be noted. If neck or shoulder pain is also present, palpate the trapezius and sterno-mastoid muscles, looking for areas of focal tenderness which might indicate referred pain from the neck to the face.

Treatment

Conservative management remains the most successful treatment for TMD and should always be tried in primary care before considering a referral. Patients must be aware of the self-limiting nature of the condition and they must understand that their role in the treatment is paramount. The success of treatment will depend upon the patient following a standardised regime:

- Medications: NSAIDs (TDS for first two weeks and as needed thereafter)

- Soft diet (liquid for first two weeks and avoidance of hard/chewy foods after)

- Localised heat (apply to affected side for five minutes TDS in evening with five minute breaks intermittent between for two weeks and as needed thereafter)

- Yawning support/avoid wide opening

- Avoidance of chewing gum/habits (e.g. nail/pen biting) and playing wind instruments.

If these simple measures fail to produce an improvement within a month, a Bite Raising Appliance (BRA) should be made and fitted. There is evidence to support the use of both soft and hard BRAs, but neither is clearly better. A soft appliance may be useful in the first instance, as is more comfortable to wear and easier to construct and fit. Some patients will find these encourage clenching; however, this does not seem to affect the success. The patient should be advised to expect this at the beginning of treatment and even some initial increase in discomfort.

Most patients will have seen a good improvement in two months of night use of a splint. In acute cases, a small dose of diazepam (2-5mg up to TDS) can be useful in conjunction with the treatments suggested above remembering to assess the impact this may have on the patient’s life and warning the patient about drowsiness and sedation from the treatment.

If there is no good improvement in this time, a referral for specialist assessment should be arranged.

Specialist referral

Onward referral to oral medicine should be made if symptoms are not improving or the symptoms are increasing despite conservative management AND provision of a BRA.

Investigations and treatment that can be carried out in specialist centre, include ultrasounds and MRI scanning to give evidence of disc displacement and Cone Beam CT to demonstrate joint degeneration. Medication, commonly a tricyclic antidepressant such as Nortriptyline, can be used at night to help with sleep, relaxation and improve pain in conjunction with conservative measures. SSRIs often exacerbate TMD pain and where patients present taking these, discussion with the GP with a view to changing the SSRI to an alternative antidepressant therapy can help treatment.

Burning Mouth Syndrome (BMS)

Background

This name encompasses a number of disorders, which include burning/pain (often of the tongue, lips and buccal mucosa) in the absence of soft tissue abnormalities, as well as a bad taste (dysgeusia), perceived dry mouth (xerostomia) with plenty of saliva present, or a feeling of paraesthesia. For this reason, the term oral dysaesthesia is often preferred. Glossodynia is another term for the same condition.

BMS is a diagnosis of exclusion and true BMS has no identifiable cause. It is a neuropathic pain in which there is either a disturbance in the way in which information is passed from the oropharynx to the brain, or the understanding of that information by the brain.

Aetiology

This is unknown. In some cases it behaves like a neuropathic pain and in others as an abnormal perception. In some patients, testing of vitamin B12, folate or iron reveals deficiencies; others have diabetes as an undiagnosed cause of dryness or neuropathy and in a few candida has been shown to be responsible for the burning. The most common finding in patients with BMS or other forms of dysaesthesia is a generalised tendency to anxiety.

Who is affected?

It is a condition which affects between 1-15 per cent of the population at some point and occurs more commonly in females particularly of peri-menopausal (as high as 40 per cent of this group), but these figures seem higher than seen in clinical practice in Scotland. Although any age can be affected, it occurs rarely in women below 30 years and men below 40 years.

Investigations

It is important to exclude lichen planus, haematinic deficiencies, diabetes and invasive candidiasis before concluding that there is an oral dysaesthesia. Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD) has been suggested as a trigger where taste is involved and a trial of a proton pump inhibitor is often given. Referral to the GP for exclusion of nutritional deficiencies and diabetes is sensible and, where oral dryness is the main complaint, a review of the patient’s medication to see if any medicines with antimuscarinic side effects can be eliminated.

Treatment

A lower soft acrylic bite splint can be helpful to avoid irritation from teeth if a parafuctional habit is present. This is particularly the case where the symptoms are predominantly present around the edge of the tongue. Chewing gum is a useful distraction from symptoms and Gelclair or similar products can be helpful to soothe and distract from the sensation. Alphalipoic acid has shown to be helpful to some patients- this can be purchased at health food shops.

Relaxation/stress reduction exercises and hypnotherapy can be useful where patients are not keen for medication but the use of a tricyclic antidepressant such as Nortriptyline for up to six months can give a good reduction in symptoms. Sometimes patients seek reassurance of the absence of pathology and have comfort in knowing their diagnosis and require no further treatment. Many have suspected that they have cancer and the dentist should always make clear to the patient that this is not the case.

Specialist referral

In many circumstances the patient can be managed in primary care by the dentist and the doctor, but where there is doubt as to the diagnosis or the patient’s symptoms fail to respond to the treatments outlined above, referral to an oral medicine specialist is needed.

Figure 2

| SOCRATES in BMS | |

|---|---|

| SITE | Anterior 2/3 tongue, anterior hard palate and lower lip most common sites |

| ONSET | Often spontaneous onset – patients often attribute to recent dental treatment, illness or medication persisting for months or years In many cases, symptoms will eventually resolve – patients are reassured by this |

| CHARACTER | Burning, scalding, tingling, metallic or foul taste Present each day, but can become intermittent as it resolves |

| ASSOCIATED FACTORS | Anxiety a very common finding Poorly fitting dentures ACE inhibitors may be linked to cause and cessation may resolve In men, adultery is an associated factor that has been seen due to guilt and associated stress |

| TIMING | Not present on waking Symptoms often become more severe as day progresses – most severe in evening Does not affect sleep |

| EXACERBATING/ RELIEVING FACTORS | Talking, eating spicy food, stressful events all make worse Relieved by eating, chewing gum and ‘being busy’ |

| SEVERITY | Varies: mild to severe |

Maxillary sinusitis

Background

Acute maxillary sinusitis produces unilateral midface pain which can be very similar in character to pulpal or periapical pain in the upper molar teeth. It should be suspected where a dental cause does not seem likely after clinical and radiographic examination of the teeth and sensibility testing. It can also be confused with TMD pain.

Who is affected?

Sinusitis rarely affects children below the age of nine years as the maxillary sinuses do not develop properly until puberty. Elderly people are at higher risk due to both a more compromised immune system and also a combination of anatomical and physiological factors such as dry nasal mucosa, weaker cartilage causing airflow changes and a diminished cough/weakened gag reflex.

Atopic individuals show a particular high risk for developing chronic sinusitis.

Aetiology

Most are viral infections. Chronic sinusitis is not painful, only acute exacerbations. There may be local nasal and sinus abnormalities contributing to the aetiology, such as polyps in the nose or sinus, septal deviation or obstruction to the meatus of the sinus in the nose. There may have been a precipitating event such as an upper molar extraction where the roots have been close to the sinus floor.

Character

Constant throbbing pain which may vary in intensity.

Associated features

There will often be a history of sinusitis and frequently an awareness of a bad taste or halitosis. This is often worse in the morning and due to pus running into the oropharynx from the nasal floor (post nasal drip). Many patients get tenderness to pressure of the cheek over the affected sinus and discomfort on pressure on the alveolar ridge between the roots of the first and second premolar teeth. The patient may report the pain as being more severe on bending forward or

lying down.

Management

If maxillary sinusitis is suspected, the patient should be referred to their GP for appropriate treatment. If the dentist wishes to give temporary supportive therapy, this can be with spray or drop nasal decongestants and not antibiotics, which are ineffective in viral infections.

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN)

Background

TN is usually a straightforward diagnosis due to the character of the pain experienced. The sudden intense and short duration of the pain means that the dental pains which can be confused with TN are acute dentine sensitivity and cracked cusp syndrome. Both of these can give similar histories in some patients where the trigger for trigeminal neuralgia is intraoral. The dentist should look carefully for evidence of these, trying agents to reduce sensitivity, testing the cusps of the premolar and molar teeth in the area of the pain.

Aetiology

The cause of TN is often unknown. Demyelination of the trigeminal nerve is a common factor, however, and this may be due to pressure from an adjacent blood vessel, or, less commonly, a tumour or other intracranial mass (2 per cent of patients) or multiple sclerosis. Diagnosis is by clinical assessment and exclusion of other causes of pain.

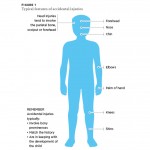

Who is affected?

Trigeminal neuralgia is a rare condition traditionally affecting an older age group, typically individuals over 50. However, many more patients now are seen in a younger age group and the diagnosis should be considered in any patient

with the characteristic pain history. More women are affected than men and the overall prevalence varies in the literature, but has been quoted at between 0.16 per cent and 0.3 per cent.

Character

The key feature of trigeminal neuralgia is the short intense pain experienced on one branch of the trigeminal nerve. This may be triggered by touch, washing, eating or a change in ambient temperature. The patient often describes the pain as being “like an electric shock” and stops them in their tracks.

However, between these, the patient is pain free, although some describe a burning feeling in the trigger area. Trigeminal neuralgia often first presents in the autumn and is frequently worse over the winter months.

Associated features

Rarely, patients will report swelling and redness in the area of their trigger.

Management

Trigeminal neuralgia requires specialist assessment and management at the beginning. Once the treatment is stabilised, the care can be continued in primary care. Primarily, this should be through the GP. A dentist suspecting TN should liaise with the patient’s GP for a referral to oral medicine or neurology and to start the patient on an appropriate medicine, usually carbamazepine whist the referral process progresses.

Although this drug is in the dental formulary, it should only be started by a dentist on the instruction of a specialist, particularly because the patient needs to have blood tests before and during treatment with this drug.

Conclusions

Although many of the pain conditions covered in this article would traditionally be referred to a specialist unit, a good history, careful examination and appropriate investigation can help establish an accurate diagnosis, which can facilitate initial management in a practice setting. This can be much more convenient for the patient and allow a much quicker start to treatment and relief of symptoms.

The simple strategies outlined above are frequently effective, making for a happy

patient and dentist. They are often the first things tried by a specialist and having this initiated in primary care means that patients subsequently passed to a specialist get quickly on to the more complex treatments where needed. Patients often have to travel significant distances for specialist care, especially in oral medicine and are often grateful for management locally. Additionally, limiting the pressures on tertiary care centres allows the patients needing this level of care to be seen more promptly.

Always try to have the same methodical process for pain history taking using SOCRATES – this will help form a logical thought process for forming a diagnosis. Employ all means of investigation prior to referral. Radiographs in particular are critical to eliminating dental sources of pain. Liaison between dentists and general medical practitioners is underutilised and is of immense benefit for complete patient care, from simple investigations to appropriate prescribing or onward referral to specialist medical services.

About the authors

Emma Finnegan graduated in Dentistry from the University of Glasgow and has a special interest in oral medicine. She currently working as a core trainee in Glasgow Dental Hospital and School.

Dr Alexander Crighton is a consultant in oral medicine and honorary senior lecturer in medicine in relation to dentistry at Glasgow Dental Hospital and School.

In children, the goal is to restore the tooth once for the lifetime of that tooth, yet full coverage restorations for primary teeth are underutilised in general practice.

The function of a crown is to protect existing tooth structure and to retain the tooth in function. Numerous clinical situations require full coverage restorations in primary molars in order to provide the most durable restoration (Table 1). Primary teeth with extensive caries can be restored most successfully with crowns. Enamel hypoplasia of the primary molars may require replacement of cusp anatomy which is also best achieved by full

coverage restoration.

Crowns also provide an optimal coronal seal for pulpally treated primary molars; research shows that indirect pulp therapy, pulpotomy and pulpectomy procedures have better outcomes as clinical success depends on protecting the tooth from the oral environment. Protection of the dentinal-pulpal complex from contamination of the oral environment also promotes healing and protects the vitality of reversibly inflamed pulp, eliminating the need for pulp therapy.

Crowns are also indicated for developmental defects of the tooth structure; teeth with extensive tooth surface loss due to attrition, abrasion, or erosion; fractured primary molars; and infra-occluded primary molars to maintain mesio-distal space (Seale and Randall 2015).

Classification of prefabricated crowns for primary molars

All prefabricated crowns for primary molars are available in varying sizes for each primary tooth type. The manufacturers seeks to replicate the height, mesio-distal width, contour and anatomy of the natural primary teeth, specifically to accommodate the convexity of the cervical margins and the exaggerated mesio-buccal bulge on primary first molars.

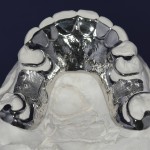

Stainless steel crowns (SSCs) or preformed metal crowns (PMCs) are widely recognised for their strength and longevity; however, due to the metallic colour, they lack aesthetics (Fig 1) (Seale and Randall 2015). Chair-side techniques for direct veneering and open-facing have been used to mask the metal colour. Over the years, alternative tooth coloured full coverage restorations have been tested using different types of dental materials and techniques with varied levels of success. Commercially fabricated preveneered SSCs combine durability and aesthetics (Leith and O’Connell, 2011; Kratunova and O’Connell, 2014; O’Connell et al. 2013). Prefabricated crowns made from composite resin, high density polymers, polycarbonate and zirconia offer a tooth coloured alternatives (Fig 2).

| INDICATIONS FOR FULL COVERAGE RESTORATIONS |

|---|

| Extensive tooth destruction – caries, erosion, developmental defects |

| Caries with > two surface involvement |

| Post pulp therapy |

| Fractured molars |

| Infra-occluding molars: to maintain mesio-distal space |

| Patients with high caries susceptibility/OH impairment /special needs |

| Caries lesions restored under general anaesthesia |

Conventional stainless steel crowns

Stainless steel crowns (SSCs) are prefabricated extra-coronal restorations which can be adapted to individual teeth and cemented in place to provide a definitive restoration (Kindelan et. al. 2008). The SSC is a durable, cost effective, minimally technique sensitive restorative option that offers the advantage of full coverage and accommodates the majority of treatment indications for primary posterior teeth (Seale and Randall 2015).

SSCs were popularised as a restorative method for primary molars in the 1950s (Humphrey 1950; Engel 1950). Over time, SSCs have been modified to improve the anatomical form and the alloy composition (9-12 per cent nickel; chromium 12-30 percent) (Randall 2002). The conventional SSCs are pre-trimmed, pre-contoured and crimped and usually need no or minimal adjustment by the operator. The conventional tooth preparation requires local anaesthesia and the tooth is prepared with 1-1.5mm occlusal reduction and minimal proximal reduction of the primary molar to allow for the crown thickness (0.2mm). The armamentarium required for placement of a SSC is outlined in Table 2.

| TABLE 2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Armamentarium required for placement of conventional stainless steel |

||

| BURS | Occlusal reduction - Football Proximal reduction - Flame |  |

| SSC INSTRUMENTS | Crimping Pliers Gordon Contouring Pliers Johnsons contouring Pliers Howe Pliers Bee Bee Curved Crown scissors Band seater |  |

| SSC KITS | Available from the major manufacturers either retrimmed, crimped and contoured, or pretrimmed with paralled walls |  |

The finish line should be a smooth feather edge at or below the gingival margin with no step or shoulder. A snap fit is achieved when the flexible metal margin passes over the buccal bulbous area and fits into the cervical constriction of the molar. SSC margins can be well adapted into the undercut areas with the help of contouring and crimping pliers (Randall 2002). SSCs cannot be used in children with nickel sensitivity. Any self-curing luting cement can be used to secure these crowns, with glass ionomer being the most popular material.

Stainless steel crowns using Hall technique

There is growing evidence that a biological approach to management of caries is effective (Kidd 2004; Ricketts et al. 2006; Thompson et al. 2008) and the technique is now gaining popularity worldwide. Isolating the caries in the tooth using a crown (sealing in caries) isolates the microflora from their nutrients reducing/eliminating their ability to cause demineralisation. The dentinal-pulpal complex is also protected from the oral environment arresting the caries process, and maintaining of the vitality of reversibly inflamed pulp.

Placement of a SSC on carious primary molars without any prior tooth preparation, decay removal, or local anaesthesia is known as the ‘Hall Technique’, named after Dr Norna Hall who had used this novel method in her clinical practice since the 1980s. The indications for Hall crowns are the same as those of conventional SSCs but cannot be used where there is a diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis or dental sepsis (Innes et al. 2009, 2011).

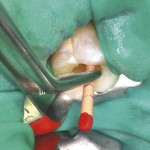

Success of the Hall technique relies on correct pulpal diagnosis. There is no need for local anaesthesia as there is no reduction of tooth structure and no caries is removed. The crown is filled with a glass ionomer cement and pushed onto the tooth thereby sealing the caries lesion from the oral environment. Sometimes, it is necessary to use orthodontic separators and a band seater to allow easier seating (Fig 3). Evidence of the clinical success of this technique after five years is very promising (Innes et al. 2011).

The crown is cemented onto an unprepared tooth causing a premature contact on that tooth. This increase in the vertical dimension of occlusion seems to be of little consequence in children, as occlusal equilibrium is re-established within two to four weeks, without any symptoms (Gallagher et al. 2014).

Preveneered stainless steel crowns

The increasing demand for a more natural appearance of primary tooth restorations led to the introduction of the commercially produced aesthetic preveneered stainless steel crowns (VSSCs) for paediatric dental patients. Recent developments in dental materials result in thermoplastic, composite or epoxy resin veneers to be bonded successfully to base metal using mechanical retention and/or chemical bonding (Hosoya et al. 2002).

The VSSCs were developed to combine the strength and durability of the conventional SSCs with the aesthetically pleasing appearance of the white veneer facing (Figure 4a, 4b). The exact specifications of the attachment, thickness and pattern of the veneer remains proprietary to the individual manufacturer. However, the makers of the current leading brands VSSCs (Nusmile, www.nusmilecrowns.com – and Kinderkrowns – www.kinderkrowns.com) have disclosed that the veneer is a composite resin material which is attached either through an intermediate bonding agent to the pre-prepared (e.g. alumina blasted) metal surface or is bonded and additionally mechanically retained to a fenestrated stainless steel core in different patterns (Fig 5).

The composite facing material requires adequate thickness for mechanical strength and ability to withstand occlusal masticatory forces. Therefore, the tooth preparation for a VSSC has to be modified to allow for this increased bulk in the occlusal and buccal surface. Greater buccal reduction is required. Local anaesthesia is required for tooth preparation with 1.5mm occlusal reduction.

Circumferential reduction is required to remove any cervical undercuts as the crown must fit passively onto the tooth. The finish line is 1mm below the gingival margin. This reduction of tooth structure is much greater than conventional SSC crown preparation but does not result in exposure of the pulp. Pulp therapy will be dictated by the extent of caries. VSSCs cannot be crimped in the areas of the facing so that limited crimping is advised only on the metal margins.

Manufacturers also warn that the metal substructure flexes from pressure during crimping, fitting or seating and this could introduce micro-fractures to the facing which subsequently can progress to veneer loss. Veneer wear or fracture may occur but the restoration will not need to be replaced as the tooth remains protected by the metal substructure (O’Connell and Kratunova 2014). Heat sterilisation may cause discolouration of the facing material and the manufacturers advise chemical sterilisation for colour stability.

- FIGURE 1 Restored primary molars showing the poor aesthetics of the stainless steel crowns in the smile.

- FIGURE 2 Prefabricated full coverage restorations currently available for primary molars in order: stainless steel crown, crown former for composite posterior strip crown, Nusmile veneered SSC, KinderKrown VSSC and a zirconia crown.

- FIGURE 3 Provision of a full coverage restoration using the Hall technique. No local anaesthesia or tooth preparation. A. placement of orthodontic separators B. space provided after 1 week C. Cementation of SSC

- FIGURE 3

- FIGURE 3

- FIGURE 4 Life-like aesthetics of pre-veneered SSC (VSSC) placed on the lower first primary molars A. the smile line and B. intraorally

- FIGURE 4

- FIGURE 5 A. The internal surface and B. external surface demonstrating differences between the various commercial brands of VSSC

- FIGURE 5

- FIGURE 6 Primary molar zirconia crowns A. Excellent aesthetics in the smile B. Intra-oral view of same child

- FIGURE 6

- FIGURE 7 Variations in the size, contour and anatomy of the various manufacturers of prefabricated zirconia crowns currently available requiring modifications in tooth preparation.

Prefabricated paediatric zirconia crowns

Zirconia has become increasingly popular as a restorative material due to its exceptional properties combining high aesthetic value and excellent mechanical characteristics (Zarone et al. 2010). Prefabricated paediatric zirconia crowns were first manufactured for clinical use in 2007. The solid zirconia construction offers high strength and durability along with superior aesthetics due to realistic anatomy and shade of the crowns (Fig 6a, 6b). It has been demonstrated that zirconia does not enhance bacterial adhesion and growth (Scarano et al. 2004) so that the surface biocompatibility and thin gingival margins of the crowns do not compromise gingival health. The colour of zirconia crowns is stable and fracture of the ceramic is unlikely given the high flexural strength and fracture toughness of the material. These crowns can be used in nickel-sensitive patients.

Zirconia is rigid and must fit passively on the tooth, therefore clinical skill is required to allow for appropriate (but not excessive) tooth preparation. The tooth preparation is critical as no crimping is possible in the zirconia crowns and adjustment of zirconia is not advised. In addition, each manufacturer of zirconia crowns emphasises different anatomical features that will necessitate alteration of the tooth preparation for maximum success (Fig 7).

Local anaesthesia is required for the tooth preparation with occlusal reduction of 1.5 – 2mm. Circumferentially, the primary tooth is reduced uniformly 1.5mm with a subgingival margin extension of 1-2mm. The zirconia crown should have a passive fit without any friction on tooth structure and no bulging of the gingival tissue. Paediatric zirconia crown kits are now commercially available in the EU and are very attractive for patients/parents and clinicians.

There are no published prospective clinical trials published so far reporting on the performance of zirconia posterior crowns, but data on anterior primary teeth shows that they perform well over time.

The general dental practitioner should use full coverage restorations routinely, especially for children with cavitated proximal lesions and in children assessed as high risk for caries. There have been significant advances in restorative paediatric dentistry and the newer options exist to provide aesthetic restorations for children.

The use of Class 2 restorations using composite, compomer, or glass ionomer should be restricted to small proximal lesions in children at low caries risk, or as a temporary solution. Selection of the most appropriate restoration must be based on the individual case and additional training will be required for clinicians to become competent in these techniques.

All these options however are valuable as part of the clinicians’ armamentarium providing restorative choice in the contemporary paediatric dental practice.

About the authors

Anne C. O’Connell, BA, BDentSc, MS, FIDT

Evelina Kratunova, BDentSc, MFD(RCSI), DCh Dent, FFD(RCSI)

References

Engel RJ. Chrome steel as used in children’s dentistry. Chron Omaha Dist Dent Soc. 1950; 13:255-258. Epidemiol. 1998; 26(1 Suppl): 8-27.

Gallagher S, O’Connell BC, O’Connell AC. Assessment of occlusion after placement of stainless steel crowns in children – a pilot study. J Oral Rehabil. 2014 Oct;41(10):730-6. 10.

Guess PC, Att W, Strub JR. Zirconia in Fixed Implant Prosthodontics. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2010 Dec 22.

Hickel R, Kaaden C, Paschos E, Buerkle V, García-Godoy F, Manhart J. Longevity of occlusally-stressed restorations in posterior primary teeth. Am J Dent. 2005 Jun; 18(3): 198-211.

Hosoya Y, Omachi K, Staninec M. Colorimetric values of esthetic stainless steel crowns. Quintessence Int. 2002 Jul-Aug; 33(7): 537-41.

Humphrey WP. Use of chrome steel in children’s dentistry. Dental Survey. 1950; 26: 945-949.

Innes N, Evans D, Hall N. The Hall Technique for managing carious primary molars. Dent Update. 2009 Oct; 36(8): 472-4, 477-8.

Innes NP, Evans DJ, Stirrups DR. Sealing caries in primary molars: randomized control trial, 5-year results. J Dent Res. 2011 Dec;90(12):1405-10.

Kidd EA. How ‘clean’ must a cavity be before restoration? Caries Res. 2004 May-Jun; 38(3): 305-13.

Kindelan SA, Day P, Nichol R, Willmott N, Fayle SA; British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry stainless steel preformed crowns for primary molars. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008 Nov; 18 Suppl 1: 20-8.

Kratunova E, O’Connell AC. A randomized clinical trial investigating the performance of two commercially available posterior pediatric preveneered stainless steel crowns: a continuation study. Pediatr Dent. 2014; 36(7):494-8.

Leith R, O’Connell AC. A clinical study evaluating success of 2 commercially available preveneered primary molar stainless steel crowns. Pediatr Dent 2011; 33:300-6.

O’Connell AC, Kratunova E, Leith R.Posterior preveneered stainless steel crowns: clinical performance after three years. Pediatr Dent. 2014 May-Jun;36(3):254-8

Ricketts DN, Kidd EA, Innes N, Clarkson J. Complete or ultraconservative removal of decayed tissue in unfilled teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Jul 19; (3): CD003808.

Scarano A, Piattelli M, Caputi S, Favero GA, Piattelli A. Bacterial adhesion on commercially pure titanium and anatase-coatedtitanium healing screws: an invivo human study. J Periodontol. 2010 Oct; 81(10): 1466-71.

Seale NS, Randall R The use of stainless steel crowns: a systematic literature review. Pediatr Dent. 2015 Mar-Apr;37(2):145-60

Thompson V, Craig RG, Curro FA, Green WS, Ship JA. Treatment of deep carious lesions by complete excavation or partial removal: a critical review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008 Jun; 139(6): 705-12.

Like most topics, decontamination has gone through phases of being high profile and then seemingly disappears off the radar. Recently, when decontamination does re-emerge, it is often when errors or omissions have been identified. It is still undoubtedly an extremely emotive issue, particularly when things go wrong. It is also a critical element as far as patient safety is concerned.

Dental practices and their teams have come a long way in the last five years as far as decontamination is concerned. We have been in a period of consolidation as far as guidance and requirements are concerned but, in my experience, we occasionally slip back into old habits. Reviewing and refreshing our knowledge and skills is essential to ensure we are following the requirements and able to show we are doing the right things to the best of our ability.

Figure 1

The decontamination cycle (Fig 1)

Decontamination is the process by which reusable items are rendered safe for further use on patients and safe for staff to handle. The process is complex and involves several stages, with potential for error throughout.

The decontamination cycle begins in the surgery with segregation of reusable items and disposal of single-use items and other materials in appropriate waste containers. Items to be processed for reuse must be transported safely to the Local

Decontamination Unit (LDU) as soon as possible. The transport boxes should be rigid, lidded, and easy to clean. These transport boxes must be easily identifiable as containing either ‘dirty’ or ‘clean’ items to avoid any potential confusion. Colour coded boxes are often the simplest way to ensure this. Using marker pens or labelling only the lids still leaves potential for error.

The next stages of the cycle are cleaning, inspection, sterilisation packing and storage.

Local Decontamination Units (LDU)

Dental practices today – space, the first frontier

Today, those considering setting up new dental practices need to make sure they have enough space to meet current requirements and ensure they are future proofing their setting. Recently, the number of dental professionals looking to set up new practices has been increasing. The settings of choice tend to be small commercial units in shopping areas where there is potential for patient footfall. I do have some concerns that, in the drive for financial viability, they are starting out with a limited area and will find they run out of space in a short time.

Despite advances in new technology, implying that practices should become more streamlined, the reality is we have many more items to house. In my experience, our need for storage capacity has not decreased despite the drive towards paperless systems and digital advances. Lack of space can result in cluttered, chaotic and disorganised settings with less potential to create a good impression and more potential for error, particularly in relation to good infection control and decontamination.

LDU compliance

Current guidance states an LDU compliant with SHPN13 is essential for primary care dental practices (Compliant Dental Local Decontamination Units in Scotland (Primary Care) (2013)).

Key points

General requirements for LDUs:

- Away from the clinical area and no activity other than decontamination undertaken

- Dirty and clean areas clearly demarcated

- Instrument flow from dirty to clean

- Smooth cleanable surfaces

- Well lit with ventilation

- Enough space for equipment and set-down areas.

Essential components

- Hand wash sink and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

- Set-down areas

- Washing sink and rinsing sink

- Washer disinfector

- Inspection areas

- Sterilisers

- Packing area.

Every dental practice in Scotland now has a room dedicated to the decontamination of dental instruments. Having an LDU is the accepted norm and is an essential requirement for the Combined Practice Inspection. These LDUs can undoubtedly vary in shape and size, but the general lay out should be in line with the single room model as stipulated in Scottish Health Planning Note 13 (SHPN13). There are sometimes some minor variations in the configuration and they may not all follow the exact requirements of SHPN13.

The design differences often relate to limited space available or build decisions determined by a contractor. Limitations such as plumbing, or other seemingly insurmountable building difficulties, have often been identified as the cause. In some cases, health boards may have agreed to minor deviations from the guidance to ensure continuance of a service when there appeared to be no other option available.

Some LDUs are undoubtedly smaller than the preferred option and space constraints are not ideal. In these circumstances, it is essential that the correct process is applied to the letter every time to avoid errors. These errors are often due to insufficient set-down space. All staff must be trained accordingly to ensure everyone knows and follows the exact procedures in place for that setting.

Other difficulties relate to using the dedicated LDU for other purposes. Again, this usually comes about due to overall space limitations in the practice. These other activities have ranged from housing X-ray developers to tea and even food preparation, neither of which is acceptable either for staff or patients. Hopefully, that message has been heard loud and clear and common sense now dictates that this is not acceptable.

LDUs are now in use across Scotland. Staff have accommodated remarkably well. I don’t believe many would wish to go back to carrying out decontamination in the clinical area. The constant background activity of washing up, while an ultrasonic rattled incessantly and autoclaves generated sauna-like conditions, was not exactly conducive to the provision of good quality patient care.

- FIGURE 2A SHPN 13 part 2 Dedicated separate Room/rooms

- FIGURE 2B Washer disinfector in LDU

- FIGURE 3 single-use symbol

- FIGURE 4 clip trays

- Tray of instruments loaded correctly for optimal processing in a non-vacuum steriliser

- Print-out showing the parameters reached during the sterilisation cycle

Single-use items

The guidance stipulates that the use of single-use items should be the option of choice where possible as long they are viable and work effectively for the purpose required. All items carrying the single-use symbol (Fig 3) should not be re-used or reprocessed. If this symbol appears on an item this is part of the manufacturer’s instructions. Compliance with manufacturer’s instructions is accepted as the legal requirement for all equipment.

Specific single-use items that have presented difficulties include:

- Three-in-one tips. Reusable metal tips are unacceptable as they are extremely difficult to clean and there are good disposable alternatives. The requirement for single use three-in-one tips is part of the practice inspection.

- Endodontic files. This has been a requirement in Scotland since 2004 and has not changed. (The situation in England is different in that they allow for re-use on the same patient. The issue with this is the exacting requirement for reprocessing and the potential for error as far as identification and storage are concerned.)

- Plastic impression trays are single-use despite the fact labs return them to practices for disposal. The effort required to clean and re-use most certainly outstrips any benefit gained considering the time and energy expended on trying to clean and prepare these for re-use.

- Matrix bands. There is evidence to show that these items, which are often heavily

contaminated with blood, cannot be cleaned effectively and present a risk to staff and patients. These must be dismantled with care and disposed of in appropriate waste containers for sharps. The holder must then be cleaned and sterilised. There are single-use alternatives.

The decontamination process

The decontamination process is about the application of knowledge and skills and is dependent on what individuals do in their own settings. The decontamination process in the LDU includes cleaning, inspection, sterilisation and packing for storage.

The general principles of the process are:

- All items should be processed according to manufacturer’s instructions. The problem with this can be that the instruction provided may not be clear or explicit. In that case, you are entitled to request information from the manufacturer or via the supplier.

- The flow of the instruments in the decontamination process is always from the dirty to clean area and never goes back in the process. The only exception would be if visible soil is picked up through inspection and the item is returned to the start of the cycle to repeat the full process.

- Using an automated cleaning process is required and washer disinfectors are essential for cleaning dental instruments.

- All re-usable items must be at least sterilised if not sterile at the point of use.

- Policies and procedures must be in place for all aspects of decontamination. All staff must have read these and can access them for easy reference.

Cleaning

Washer disinfectors – the final hurdle for compliance?

“Use of a washer disinfector (WD) is a requirement for compliant reprocessing of dental instruments” (Compliant Dental Local Decontamination Units in Scotland (Primary Care) (2013)). Using a washer disinfector is the preferred method for cleaning dental instruments because it offers the best option for the control and reproducibility of cleaning. This means the cleaning process can be validated. WDs are used to carry out the processes of cleaning and disinfection consecutively.

A typical WD cycle for instruments includes the following five stages:

- Flush – Removes gross contamination. Latest standards indicate that a water temperature of <45°C is used to prevent protein coagulation and fixing of soil

to the instrument - Wash – Removes any remaining soil. Detergents used in this process must be specified by the manufacturer as suitable for use in a WD

- Rinse – Removes detergent used during the cleaning process.

- Thermal disinfection – The temperature of the load is raised and held at the pre-set disinfection temperature for the required disinfection holding time: for example, 80˚C for 10 minutes, or 90˚C for one minute

- Drying – heated air removes residual moisture. Some manufacturers have worked on this in an effort to reduce cycle times as this was a significant barrier to their use. They have endeavoured to reduce the cycle times to improve efficiency for use in practice and while still demonstrating effective cleaning efficacy as per testing requirements.

What have the problems been?

It is safe to say that the dental profession in Scotland has been slow to adopt this piece of equipment as a ‘must have’ as they strive towards best practice in decontamination.

The reasons for this are varied and complex. The reputation of these items have been somewhat tarnished often through anecdote and bad press. Admittedly, this was not helped by some genuine technical problems related to specific machines resulting in some practitioners experiencing difficulties despite their best efforts. Negotiations with suppliers and manufacturers have been ongoing in an effort to resolve specific cases. From the outset, some practitioners heard about these problems and simply decided not to try for themselves.

Another difficulty with washer disinfectors was that they didn’t fit naturally and seamlessly into our existing processes. We had to change aspects of what we did to make them work efficiently and effectively for us. Change is difficult and it takes time. The early abandoners ran out of patience and gave up quite quickly. Some of the more tenacious teams persevered and have become converts. Recently, I have had some surprisingly positive feedback from some of the more strident early objectors.

The fact is, these machines are an essential requirement in Scotland to ensure our reusable instruments are clean and able to be sterilised effectively.

To utilise a washer disinfector efficiently and effectively, in my opinion, we need several things. First of all, you need have done a capacity calculation to work out which washer disinfector suits the needs of your practice. The overarching aim is ultimately to run the washer disinfector a minimum number of times a day and only put it on when it’s at or close to its full capacity. To work that out, you need to look at:

- How many items are used in the practice in an average session?

- What does the WD hold?

- Could the internal set-up be improved to hold more?

- How long will it usually take to get the WD to capacity?

- How long does the full decontamination cycle take?

- Do you have enough stock of instruments to avoid shortages at busy times?

In my opinion, using clip trays (Fig 4) for cons kits are essential to allow the WD to work efficiently for you. The initial capital outlay will save running cost in the longer term. It also reduces risks for staff having to spend time dismantling open trays, which need to cleaned separately and then reassembled before storage.

Members of the dental team who work in the LDU are best placed to work this out and establish a routine that suits the way the practice works and use the WD efficiently and effectively.

Ultrasonic cleaners

Compliant ultrasonic cleaners are also an automated cleaning method. They are useful as a back-up cleaning method. They are no longer an essential requirement as far as the practice inspection is concerned as washer disinfectors are the first line cleaning method and an essential requirement.

Ultrasonic cleaners can be utilised to pre-clean particularly heavily soiled instruments before processing in the washer disinfector. This is useful if there is a delay before the washer disinfector is at capacity and heavily contaminated surgical kits would become difficult to clean if left to dry out. Pre-cleaning is advisable in that situation.

Using an ultrasonic cleaner if the washer disinfector is down for short periods is acceptable. The ultrasonic cleaner will have to be validated and tested as per manufacturers’ instructions to ensure it is functioning effectively if it has to be brought back into use. In a busy practice, an ultrasonic alone may not provide the capacity required to ensure throughput and it may be necessary to revert to full manual cleaning as well.

Reverting to full manual cleaning utilises significant volumes of hot water,

detergent and staff time. It also puts your staff at risk of injury. Using manual cleaning should only be adopted as a last resort for cleaning dental instruments. When service and maintenance contracts for washer disinfectors are being arranged some assurance from the supplier as to their response time and contingency plans, if the washer disinfector fails, should be sought. Details of full manual cleaning process can be found in The SCDCEP guidance document – Cleaning Dental Instruments, can be accessed at www.sdcep.org.uk/published-guidance/decontamination/

Handpieces and washer disinfectors

Cleaning handpieces effectively due to the extremely narrow lumens is a difficulty. As far as I am aware, there has been little progress on effective handpiece cleaning in washer disinfectors. Some practices are processing handpieces in their washer disinfectors without detriment to their equipment. Most practices are understandably tentative about putting these delicate, expensive items in their washer disinfector. There is no specific guidance that stipulates this is a requirement. If you plan to process handpieces in a washer disinfector, make sure you have written instructions and an assurance of compatibility from both the handpiece and the washer disinfector manufacturer.

Decontamination process – sterilisation

All reusable items must be sterilised. From time to time we come across situations where there is some confusion as to what type of autoclave is in use or which cycle is being used. It is imperative that the whole dental team understands the difference between vacuum and non-vacuum cycles in benchtop sterilisers to ensure these are used safely and effectively.

- A non-vacuum cycle can only be used for unwrapped items. When the cycle is complete, the items will have been sterilised.

- It is essential that any steam steriliser is not overloaded.

- If a vacuum cycle is used, items can be wrapped or bagged before sterilisation. When this cycle is complete, the items will be sterile as long as the packaging is intact.

Please note, if items are wrapped before being placed in a non-vacuum cycle. they will not have been sterilised. If these items were subsequently used. this presents a significant risk to patient safety. This is a serious event and must be reported.

Maintenance, testing and validation of all decontamination equipment

There tends to be some confusion as to what is required as far as testing and validation of equipment is concerned and what your engineer, supplier or manufacturer provides as part of contractual arrangements.

Maintenance contracts for your decontamination equipment are required to make sure the equipment is in good mechanical working order. You may have options as far as the cover you choose. Make sure you are certain which cover you are paying for and exactly what it includes. Testing and validation are not the same as general maintenance. Your engineer may do this at the same visit as part of the contract. Always make sure you know exactly what they have carried out and retain all paperwork as evidence.

Validation is a documented procedure used to show that the decontamination process will repeatedly and consistently take place to a satisfactory standard when defined operating conditions are used. Validation checks and tests are carried out at least annually, which is referred to as revalidation. Some manufacturers may refer to this as annual testing rather than revalidation.

Periodic testing is required to ensure that WDs perform consistently as specified at validation.

Tests and testing intervals will be stipulated in manufacturer’s instructions. Some of these tests will be carried out by practice personnel and provide regular checks to evidence that equipment is operating as per the parameters determined at validation.

A test person (engineer) will carry out periodic testing/revalidation as specified in the manufacturer’s instructions. This will be required at least annually. Always check with your engineer and make sure you know what is being carried out at each visit.

Testing carried out by practice teams include:

- Automatic control tests. These are required for washer disinfectors, ultrasonic baths and autoclaves. Details on how to perform automatic control tests can be found in the SDCEP decontamination guidance: www.sdcep.org.uk/published-guidance/decontamination/

- Cleaning efficacy tests are used to demonstrate the ability of washer disinfectors and ultrasonic baths to remove soil and contamination. Consult your manufacturer to see which tests are recommended and how often these should be done.

Storage

As far as storage of dental instruments after sterilisation is concerned, the general principle for all reusable items is to ensure that the potential for re-contamination through direct contact or aerosol production is eliminated.

Aerosol production during clinical procedures presents a risk of contamination of surfaces and items within the area. Aerosols contain blood, saliva and significant levels of associated micro-organisms. This can constitute a risk of transmission of infection as many of these micro-organisms can survive on surfaces for variable periods of time. Thorough environmental cleaning and closed storage must be applied to avoid potential risk of transmission of infection.

The practice of bulk storage of items for intraoral use should be discontinued. Using drawer inserts to store loose mirrors and probes is not acceptable as far as avoiding possible contamination is concerned. Storage options include the bagging of examination and other kits. Bagging of forceps and other items for oral surgery has been accepted as the norm for some time. Conservation kits in clip trays should be stored covered with a lid or bagged and can be placed in cupboards in racks or drawers either in the clinical area or in a central storage area.

All items for clinical procedures should be set out for use on each patient immediately before the treatment episode. During clinical procedure, when extra items stored in drawers or cupboards are required, good local systems for retrieval to avoid potential contamination of other items must be in place. This may involve glove removal and use of clean tweezers to ensure efficient safe practice.

Practices may have adopted different ways of fulfilling the requirements for storage related to their specific storage spaces and practice layout. Avoiding the potential for recontamination is essential and should be considered fully to ensure there are safeguards to ensure the risk of this is eliminated as far as possible.

In general:

- No unnecessary items intended for clinical use should be set out on work surfaces during clinical procedures. Reduced clutter means easier cleaning.

- Items set out for a specific patient treatment and not used must be fully reprocessed or disposed of if single use.

- Sterilised items even in closed storage such as cupboards or drawers should be covered.

There is no specific guidance in Scotland as far as the timescale for safe storage of non-sterile or sterile items. HTM 0105, the guidance applied in other areas of the UK apart from Scotland, stipulates more exacting requirements for storage (click here to see PDF)

Training

The need for suitable training enabling the application of good infection control and decontamination, in line with Scottish guidance, is essential for the whole dental team. Another essential requirement is quality assurance. Audit is the accepted method of choice. This is essential, not only for infection control purposes, but also to fulfil NHS terms of service.

NHS Education for Scotland can provide both and help to avoid the pitfalls.

Our national infection control support team is made up of dental nurses with extensive experience both in practice and as trainers. They have been trained specifically to Scottish infection control and decontamination guidance requirements. They have a wealth of knowledge and are fully aware of the differences in guidance in others parts of the UK. Our team can tailor sessions to meet any needs the practice feel they have. For example. if you are struggling to integrate your washer disinfector into your usual process. our team can help.

The training does provide knowledge, but the real focus is on practical application. In a busy practice, knowing what to do doesn’t mean we all do it every time. Our sessions are designed to identify what makes the application of that knowledge challenging and what might help to make that change. Providing the practice with an action plan is an essential element to enable these changes. This plan will be supported and followed up. We also have two short e-learning programmes that are useful for updates or induction for new staff. These can be accessed though the NHS Education Portal (https://portal.scot.nhs.uk/)

On request, in conjunction with booking a training session, dentists can access four pre-populated audits via the NES Portal covering four areas of infection control and decontamination. Our team can review data collection and provide feedback on audit reports. After submission of a satisfactory report, dentists will have evidence of quality assurance in their practice and be eligible for audit hours and allowance.

NHS Education for Scotland has worked hard over the last years to ensure a consistent message based on Scottish guidance requirements has been delivered to the whole dental team in every practice in Scotland. NES has delivered 2,313 in practice training sessions to 6,511 dentists and 1,335 DCPs.

The message is out there. If you feel your team could benefit from our training, please contact Natalya.Zhernakova@nes.scot.nhs.uk or call 0141 352 2642.

About the author

Irene Black graduated from Glasgow University in 1980, gained her Membership of the Faculty of General Dental Practitioners in 1999 and the Certificate in Effective Dental Management in 2005.

Along with her husband, she owned an NHS dental practice in Eaglesham for 27 years where she continues to work on a part-time basis.

Irene has been a dental practice adviser in Greater Glasgow and Clyde health board for 14 years and her interest in education developed during nine years spent as a vocational trainer.

She has worked as an assistant director for NHS Education with the remit for infection control and decontamination for the last eight years. This has included developing both in-practice and other training packages for the dental team. As part of this role, she has worked with Scottish Government and other NHS organisations in an effort to determine how the difficulties related to decontamination in dental services might be resolved.

Irene also works with the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme in guidance development and research.

References

Scottish Health Planning Note 13 Part 2, Local Decontamination Units (www.hfs.scot.nhs.uk/online-services/publications/decontamination/)

Local Decontamination Units: Guidance on the Requirements for Equipment, Facilities and Management (www.documents.hps.scot.nhs.uk/hai/decontamination/publications/ldu-001-02-v1-2.pdf)

Compliant Dental Local Decontamination Units in Scotland (Primary Care) (2013) (http://www.hfs.scot.nhs.uk/publications-1/decontamination/)

Modern dentistry has undergone a revolution in the area of cosmetic or aesthetic dentistry. Patients more frequently put an emphasis on improving the appearance of their teeth and often have high expectations. This article aims to demonstrate some factors that need to be considered and techniques used in order to achieve this goal. Clinical cases will be used to illustrate this process.

Patient history

Patients who wish to improve the appearance of the front teeth generally do so as there is a particular feature of their smile with which they are unhappy. Discolourations, previous dentistry, missing teeth, misshapen teeth, excessive gingival display, gingival recession, tooth crowding, spacing or movement are some examples of the dental factors affecting the smile (Figs ı and 2).

Depending on the individual patient’s presentation, different treatment options may be indicated to achieve their goals. The most important factor for success is accurately distilling from the patient what particularly concerns them about their teeth. Once this has been established, the clinician can then begin to visualise how the case will look upon completion. It goes without saying that it is particularly important to undertake a thorough extra-oral examination (Table ı). The clinician should be looking for any indications of factors that are detrimental to the appearance of the teeth.

During the intraoral examination, attention should be given to the occlusion, both static and dynamic, as this may influence the treatment plan, restoration type, number of teeth to be restored and even the materials to be used. Of importance also is the presence of tooth wear. Its location, distribution and characteristics will point to the underlying aetiologyı and correct management. A diagnosis of bruxism or parafunction may impact on the treatment plan.

Dento-gingival complex and importance of pink aesthetics

An understanding of the normal size, shape, position and arrangement of the natural dentition is essential. Much has been written about certain values or proportions that are key to a “perfect smile” but in reality, there is no single formula for all.

In practical terms, average anterior tooth size2, height:width ratios2 and relative proportion of anterior teeth3 are of use. This information can be taken together with a desired incisal edge position of the final restorations to arrive at a tentative starting point. When restoring anterior teeth, the most important starting point is the proposed final incisal edge position as this then determines tooth size and length. This may have important consequences on the gingival margin positions in order to maintain ‘ideal’ tooth proportions for an aesthetic outcome (Figs 3 and 4).

An example of this would be where tooth wear has occurred and the worn teeth may have experienced compensatory over-eruption maintaining the position of their incisal edges. In this instance, further addition to the incisal aspect of the teeth would not result in an aesthetic outcome and consideration must be given to either orthodontic repositioning of the teeth prior to restoration, or possibly crown lengthening to reposition their gingival margin levels.

The relationship of the periodontal tissues – in particular, the gingival margin positions, symmetry, interdental papilla and amount of gingival display – are all important (Fig 5). Much has been written on the need for aesthetically correct gingivae to frame the teeth or restorations to provide highly aesthetic outcomes. Periodontal plastic procedures can aid the outcome of restorative dentistry, so co-ordination with periodontal colleagues is vitally important. An understanding of the limitations of grafting procedures is also important and the use of alternatives, in particular the use of pink porcelain, should be considered (Fig 6). Careful communication with your laboratory is needed in order to develop natural-looking prosthetic gingivae.

- Patient A intra-oral. Discoloured, leaking restorations. Teeth are too broad and have poor axial alignment

- Patient A smiling. Poor smile aesthetics, occlusal plane disruption and poor tooth form

- Patient A – provisional restorations with corrected incisal edge position

- Patient A – in order to develop correct tooth size (Height:Width ratios) minor crown lengthening was undertaken

- Patient B – combined vertical and horizontal ridge defect with loss of gingival architecture

- Patient B – use of pink porcelain to create an artificial interdental papilla and achieve more ideal pink-aesthetics

Excessive gingival display (gummy smile)

Most often as restorative dentists we are challenged by a deficiency in periodontal tissues either as a consequence of periodontal disease or tooth loss. However, an excess of gingival tissue display can also be unsightly and can lead to a patient being unhappy with their gummy smile (Table 2).

In certain instances, subtractive periodontal procedures alone can be sufficient in the management of such cases. Where roots of teeth may become exposed by surgical crown lengthening procedures, root coverage may become necessary and should be planned for.

Depending on the aetiology and the contributing factors, dentistry alone may not provide the solution. Orthodontic treatment in isolation or together with maxillofacial or plastic surgery may be necessary to achieve the ideal aesthetic outcome, therefore a careful assessment should be made for such patients prior to treatment.

- Patient A – smooth tooth preparations and well-fitting provisional restorations allow for maintenance of periodontal health and ease of impressions

- Patient A – final restorations with improved proportions, alignment and characterised porcelain

- Patient A – overall improvement in smile from restoring six anterior teeth

- Patient C – bright natural teeth with minor surface loss

- Patient C – conservative preparations and restoration with feldspathic veneers to improve appearance

- Dark crown preps with discoloured cores

- Opaque zirconia based restorations to mask underlying discolouration

Treatment planning: diagnostic wax-up or virtual smile design

Before making any reversible alterations to the existing teeth, it may be necessary to undertake a diagnostic wax-up. This is of particular importance if changes are planned in relation to tooth size, shape or position. This can aid in patient acceptance, but more importantly gives a clear indication of the proposed final appearance of the teeth.

More recently, digital manipulation of clinical photographs using dedicated software has become available and this can be very useful to contrast pre-op images and planned results. Ideally, some form of temporary mock-up should be provided to see the effects of proposed changes in the patient’s mouth. This is not always feasible, as in some instances subtractive changes are being planned and this is where virtual smile design has an advantage.

Provisionalisation and tissue management

Once a treatment plan has been accepted and teeth have been prepared, careful provisionalisation following the blueprint of a diagnostic wax-up may be required. A period of time spent in provisional crowns can be useful for a number of reasons. This gives the clinician an opportunity to review questionable teeth, assess planned occlusal changes and finally review with the patient any alterations and their effects on the final aesthetic arrangement of the teeth. Should further changes be requested, provisional crowns can easily be adjusted and once acceptable can then be copied to create a go-by cast to be followed in final restorations.

In order to achieve acceptable aesthetic results with anterior crowns, subgingival crown margin placement is generally required. The maintenance of periodontal health is essential in order to allow for accurate impressions of the prepared teeth. Highly accurate impressions of stable gingival tissues allow for crowns to be made precisely resulting in better marginal fit and ongoing periodontal health. This is essential for predictable long-term aesthetic success (Fig 7).

Tooth colour: selection of appropriate materials

Patients generally do not complain that their teeth are too light and trends towards brighter teeth are seen in everyday practice. When restoring anterior teeth, the colouration of the prepared teeth should be carefully considered.

How light will interact with the final restorations is important here. Currently available indirect restoratives can be grouped according to their degree of translucency or opacity. Indeed, some currently available systems offer a range of translucency depending on the prevailing clinical conditions (Table 3).

In achieving the most aesthetic outcome, a balance must be struck between the nature of the prepared teeth, selection of the appropriate restorative materials and the degree of tooth preparation undertaken. The ideal situation would consist of a naturally coloured tooth allowing for a translucent restoration with minimal tooth preparation (Figs ı0 and ıı).

The other end of the spectrum, however, is also frequently encountered. Teeth that are highly discoloured will require more opaque restorations to mask their underlying darkness and the ceramist will need additional thickness of porcelain to create lifelike restorations. Unfortunately, there is no perfect system for all eventualities.

In the author’s opinion, there is still a place today for porcelain fused to metal crowns on anterior teeth in aesthetic dentistry in selected cases. Excellent results can be achieved when the ceramist is given enough room in terms of tooth preparation for creating natural-looking porcelain.

In order for our technicians to achieve the results we desire, as much information as possible should be made available to them. The final desired shade often is not enough and the shade of the prepared tooth stump should also be indicated. Photographs of prepared teeth are beneficial in this respect (Figs 12 and 13).

Customising the smile

When considering “ideal” aesthetics using “normal” measurements and relationships there can be a tendency towards arriving at an artificial or a “too-perfect” result. Many discerning patients want their teeth to be improved upon, but also request that the end result appears natural.

Nature inevitably demonstrates some asymmetries

and this usually adds character to an individual’s smile. Minor tooth rotations and attention to detail in terms of surface texture and shading can go a long way to achieving this goal.

Incorporating characteristics from the patient’s own natural teeth into the final restorations can also be a useful tool. Photographs of unprepared healthy adjacent or opposing teeth offers the ceramist an idea of shade transitions, enamel surface texture, tooth form and translucency and adds to the overall micro-aesthetics of the case (Figs 8 and 9).

Tables

| Table 1: Extra-oral examination | |

|---|---|

| FACIAL VIEW: | |

| Occlusal plane orientation | Tooth display (incisal edge position) |

| OVD assessment | Gingival display |

| facial symmetry/centre lines/alignment of teeth | |

| SAGITTAL PROFILE: | |

| Skeletal pattern. | OVD assessment |

| Labial-lingual position of incisor teeth | |

| SMILING VIEW: | |

| Smile line-normal, flat, reversed | Tooth display |

| Gingival display | buccal corridor |

| Tooth colour | Any other obvious deviations from ideal |

| Table 2: Factors associated with excess gingival display | |

|---|---|

| Tooth position | Large maxilla (vertical maxillary excess) |

| Delayed passive eruption | Gingival overgrowth |

| Short upper lip | Hyper-mobile upper lip |

| Table 3: Translucency of commonly used indirect restorative materials |

||

|---|---|---|

| TRANSLUCENT MATERIALS | VARIABLE TRANSLUCENCY | OPAQUE MATERIALS |

| Feldspathic Porcelain | E-Max | Zirconia based |

| Empress Esthetic | Procera Alumina | Metal-ceramic |

About the author

Dr Tom Canning, DentSc MFD (RCSI) DChDent (Prosthodontics), is a specialist prosthodontist and maintains a specialist prosthodontic practice at Clontarf Aesthetic Dentistry, 9 Clontarf Road, Dublin 3. Contact the practice at 00353 (0) 1 525 0490 or by visiting www.clontarfaestheticdentistry.com

References:

- Verrett RG (2001): Analysing the aetiology of an extremely worn dentition. J. Prostho; 10:224-233.

- Width/length ratios of normal clinical crowns of the maxillary anterior dentition in man. Sterrett JD, Oliver T, Robinson F, Fortson W, Knaak B, Russell CM. J Clin Periodontol. 1999 Mar;26(3):153-7

- Dentists’ preferences of anterior tooth proportion-a web-based study. Rosenstiel SF, Ward DH, Rashid RG. J Prosthodont. 2000 Sep;9(3):123-36

The following case reports on a patient initially referred for dental implant rehabilitation of posterior segments who, following comprehensive planning, elected for an entirely different treatment option.

The case

The patient was a 60-year-old female with a heavily restored upper and lower dentition. She was referred

for possible implant replacement of upper and lower posterior dentition.

Previous dental history

She was a regular attender with significant restorative care over her lifetime, most recently restorations and tooth loss required as teeth have failed due to loss of tooth structure.

Last treatment was fabrication of a new upper p/- chrome and RCT of lower 6s following crown loss.

Medical history

Slightly elevated blood pressure, controlled, otherwise clear.

Patient requirements/goals

- Aesthetics was the highest priority. She disliked the spaces in the upper and lower posterior segments as well as visible clasps of upper chrome (Fig 1).

- Longevity and planning for future problems was important.

- She would also like to improve function.

Patient assessment

Extra-oral

Soft tissue assessment – no abnormalities detected.

Smile line – medium/high, showing gingival margins during a wide smile.

Intra-oral

Soft tissue assessment – no abnormalities detected.

Teeth present:

7__4321 – 12345_7

76__321 – 123__67

(Figs 2-4)

Restorative status and prognosis of remaining teeth:

Maxillae