In recent years dentistry has advanced from more than just oral health to overall health. One of the outcomes of this is dental sleep medicine – the management of snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), both of which are classed as a sleep-related breathing disorder (SRBD). Approximately one in 30 people in the UK complain about headaches each year and it is estimated that around 1.5 million adults have OSA, although only around 330,000 are currently diagnosed and treated. These numbers are increasing as obesity levels rise in adults and children. In a UK cross-sectional study, 12 per cent of children were found to be habitual snorers and 0.7 per cent were found to have obstructive sleep apnoea 1.

Understanding sleep apnoea and snoring

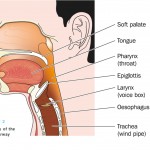

OSA is a sleep-related respiratory condition, leading to intermittent cessations of breathing due to a narrowing or closure of the upper airway during sleep. Symptoms of OSA often include excessive daytime sleepiness, snoring, and witnessed apnoeas or hypopnoeas (collapse of the airway leading to breathing cessations). Although OSA is thought to be a disorder affecting the overweight or obese, it can affect anyone and is estimated to affect 1.5 million adults in the UK, men, women and children.

Craniofacial pain and TMD

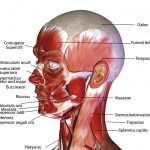

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD) refers to a group of disorders affecting the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), masticatory muscles and the associated structures (Fig 1). Common symptoms of TMD include pain, limited mouth opening and joint noises (also known as clicking of the jaw).

TMD symptoms affect up to 25 per cent of the population with only 5 per cent seeking medical help for their symptoms – they simply put up with the pain or can’t find a treatment 2. TMD can occur at any age but is more common among women and those between the ages of 20 and 50.

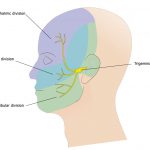

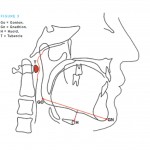

The main sensory nerve system running through the head is the trigeminal nerve system (Fig 2) and accounts for 90 per cent of all the sensory input into the entire nervous system. Because of this we can explain why TMD can sometimes lead to debilitating symptoms for those who suffer from this condition. Many patients will seek treatment for craniofacial pain due to recurring migraines, but 90 per cent of headaches are really caused by disorders in the facial muscles and nerves.

- Figure 1 – Muscles of the face including the masticatory muscles

- Figure 2 – Trigeminal nerve – the three different innervation areas of the head

- Figure 3 – Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine in use

A connection between sleep apnoea and pain

As research continues to advance we see a clear connection between sleep-disordered breathing, craniofacial pain and TMD, which requires proper evaluation and diagnosis by dental and medical teams. Essentially, it is the dental clinician who will often evaluate, refer and possibly manage these issues which impact such a large percentage of the population.

There is ample evidence to suggest that sleep apnoea and pain are related, but many questions still remain. One main trend emerging pertains to the directionality and mechanisms of the association of sleep apnoea and chronic pain. It appears that sleep disturbance may impair key processes that contribute to the development and maintenance of chronic pain, including joint pain (TMD). In a recent study, sleep disturbance and pain were connected. It determined that pain not only has direct effects on the person’s health, but also an association with sleep disturbances

Many studies have suggested that experimental sleep disruption results in enhanced pain perception and interactions between sleep and pain. It is suggested that experimental sleep disruption results in enhanced pain perception, that poor sleep is correlated with elevated pain severity in chronic pain patients and that in the general population, individual differences in sleep impact on subsequent pain. A study published in the European Journal of Pain stated that sleep fragmentation among healthy adults resulted in subsequent decrements in endogenous pain inhibition 3.

With an evident relationship, we look to understand that clenching or grinding of one’s teeth is a way for the brain to protect itself from suffocation during sleep 4,5,6,7,8. The screening process is important in helping us identify bruxism as either a cause of TMJ/craniofacial pain or a protective mechanism in sleep disordered breathing 9,10,11,12. By identifying this link between the three conditions we can properly manage each disorder.

Dental solutions for proper treatment

Patients who suffer from severe sleep apnoea might opt for surgery for treatment. However, sleep apnoea surgeries have a history of causing the patient excruciating pain. The gold standard for severe OSA patients is use of the continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine (Fig 3), with success ranging in various studies from 90 to 95 per cent. However, the problem with CPAP treatment is patient non-compliance and intolerance. When people return home, there is a good chance they just won’t use their machine 13.

There are challenges posed by sleep apnoea and craniofacial pain which span the research spectrum – from causes to diagnosis through treatment and prevention. It is important for us all to work together to gain a better understanding of sleep apnoea, the TMJ and muscle disease process and craniofacial pain, as well as improving quality of life for people affected by these disorders.

Dentists see their patients more often than family doctors, as it is recommended that patients visit a dentist at least twice a year. Since we are typically seeing our patients more often, it is important to understand sleep apnoea, TMD and craniofacial pain, as well as gaining an understanding of the right questions to ask.

As only one out of 20 UK patients suffering from pain actually seek treatment and that 85 per cent of patients with sleep apnoea either don’t or do not know where to seek help, it is vital that we ask the right questions in order to gain a proper diagnosis. If they are suffering from pain they might not realise the solution can be found at the dental practice:

- Palliative care – medications to better improve a patient’s pain

- Changing a patient’s diet – this would include soft foods or foods that don’t overextend the jaw or cause pressure on the head. For sleep apnoea it would include foods to help in weight control or loss

- Oral appliance therapy and orthodontics – offer a way to realign the jaw and teeth to relieve pressure on the face and jaw while preventing the tongue from falling over the airway.

Dentists hold the key to successful management of sleep apnoea and pain among patients who might think a solution is not possible. It is our responsibility to continue to advance our knowledge of various areas of dentistry we might not be exposed to in our undergraduate training – there is more out there than we were taught.

Advanced education

As dentists we must look to better understand sleep apnoea, snoring and craniofacial pain in order to provide our patients with the care they need to live a good quality of healthy and happy lives. Further education through lectures and seminars becomes essential with a wide range of continuing education courses available. Only through education can we continue to offer the help that patients with this debilitating condition need.

Since this is not a subject that is covered in the undergraduate curriculum, postgraduation certification in dental sleep medicine and craniofacial pain allows the whole team to engage with various medical and dental specialities to offer the optimum management options to these patients.

The British Society of Dental Sleep Medicine (BSDSM) has for many years run one-day dental sleep medicine courses which have proved very popular. As well as providing an overview of sleep disordered breathing, advising how to identify and safely assess patients at risk and explaining treatment and management options, the courses now include a module on temporomandibular joint dysfunction and craniofacial pain.

The BSDSM also provides a wealth of information on snoring and OSA, advice on treatment options for the public, patients and healthcare professionals and promotes discussion on dental sleep medicine. For more information, visit www.bsdsm.org.uk

About the author

Dr Mayoor Patel DDS, MS, D.ABDSM, DABOP, DABCP, DABCDSM, DAPPM, RPSGT, FAAOP, FICCMO, FAACP, FAGD is owner of the Craniofacial Pain Center of Georgia in the US, co-owner of MAP Laboratory LLC and Director of Clinical Education at Nierman Practice Management. He is a board member of the American Board of Craniofacial Pain, the American the Academy of Craniofacial Pain, the American Board of Craniofacial Dental Sleep Medicine and a director of the Georgia Association of Sleep Professionals.

Dr Aditi Desai BDS, MSc is president of the British Society of Dental Sleep Medicine (BSDSM). She has accreditation from the European Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine and serves on the Council of the Odontological and Sleep Section at the Royal Society of Medicine (RSM). Dr Desai limits her practice predominantly to the management of sleep disorders. Based in Harley Street and London Bridge Hospital, she works with other eminent physicians and ENT consultants as part of a multidisciplinary team of like-minded professionals with special interest in sleep medicine. She is an invited speaker at the RSM, the Royal College of Surgeons of England, the British Sleep Society, the British Dental Association and many other organisations. She has published several articles in dental journals on dental sleep medicine and lectures on the subject in the UK and internationally.

References

1. Ali NJ, Pitson DJ, Stradling JR. Snoring, sleep disturbance, and behaviour in 4-5 year olds. Arch Dis Child 1993; 68(3): 360-6.

2. Murphy, M.K., et al., Temporomandibular Joint Disorders: A Review of Etiology, Clinical Management, and Tissue Engineering Strategies. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants, 2013. 28(6): p. e393.

3. Edwards, R., et al., Sleep continuity and architecture: Associations with pain-inhibitory processes in patients with temporomandibular joint disorder. European Journal of Pain, 2009. 13(10): p. 1043-1047.

4. Ng, D.K., et al., Prevalence of sleep problems in Hong Kong primary school children: A community-based telephone survey. Chest, 2005. 128(3): p. 1315-1323.

5. Phillips, B., et al., Effect of sleep position on sleep apnea and parafunctional activity. Chest, 1986. 90(3): p. 424-429.

6. Bailey, D.R., Sleep disorders. Overview and relationship to orofacial pain. Dental clinics of North America, 1997. 41(2): p. 189-209.

7. Hosoya, H., et al., Relationship between sleep bruxism and sleep respiratory events in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Breath, 2014. 18(4): p. 837-44.

8. Saito, M., et al., Temporal association between sleep apnea-hypopnea and sleep bruxism events. J Sleep Res, 2013.

9. Blanco Aguilera, A., et al., Relationship between self-reported sleep bruxism and pain in patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil, 2014. 41(8): p. 564-72.

10. Manfredini, D. and F. Lobbezoo, Relationship between bruxism and temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of literature from 1998 to 2008. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology, 2010. 109(6): p. e26-e50.

11. Unell, L., et al., Changes in reported orofacial symptoms over a 10-year period as reflected in two cohorts of 50-year-old subjects. Acta Odontol Scand, 2006. 64(4): p. 202-8.

12. Ahlberg, K., et al., Perceived orofacial pain and its associations with reported bruxism and insomnia symptoms in media personnel with or without irregular shift work. Acta Odontol Scand, 2005. 63(4): p. 213-7.

13. Richard, W., et al., Acceptance and long-term compliance of nCPAP in obstructive sleep apnea. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 2007. 264(9): p. 1081-1086.

Make no mistake, we’re no longer mimicking the US culture of litigation – we’re now leading the world. So, whether you’re a dentist, a doctor, or in the business of offering legal representation to either, it’s well worth understanding just who’s driving this financially and emotionally expensive cultural revolution. Is there a particular species of litigious patient, and if so, what do they look like?

The answer is obviously ‘no’, but there are certainly patterns of behaviour and traits of character that have become apparent to me during more than 30 years as a restorative dentist, and as an expert witness with experience of both sides of the judicial fence. Of course, it’s preferable to avoid any patient-practitioner relationship developing into full-blown litigation in the first place. Complaints invariably originate from poor communication, and can be provoked by what is said, is not said, or both.

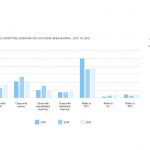

My own audit of more than 20 years of documentation revealed the following triggers that led to the patients issuing civil proceedings, in descending order of frequency:

1. A sense of abandonment and failure to respond when problems became apparent.

2. Miscommunication with an English-speaking patient due to the clinician’s mother tongue not being English.

3. Failure to identify that the clinician is out of his/her depth and a referral to a colleague clearly indicated.

4. The absence of the usual clinician due to illness or holiday, causing the patient to attend another practitioner who makes a negative comment about their dental state, eg untreated periodontal disease or tooth decay.

5. Failure to adhere to well-established clinical protocols, with specific reference to alternative therapies with no scientific or clinical data to support their use.

6. Early failure of the treatment with unsuccessful efforts to resolve the problems.

7. A report that the clinician was too brusque and/or rude and appeared in a hurry.

8. Patients reporting that the clinician lost his cool/patience and/or shouted at them.

It often transpires that the ‘offending’ practitioner has chivvied a patient into making a choice using demanding or dictatorial language, whether real or perceived. A recent review of complaints carried out by one of the leading dental defence indemnity insurers concluded that more than 70 per cent of complaints were attributed to poor communication, highlighting not only indelicate vocabulary but the manner of delivery and body language, suggesting a lack of ‘feeling’ or compassion.

In contrast – and in a great many of the cases I’ve encountered – clinicians attempt to abandon the patient by not responding to letters of complaint and not returning phone calls. An apology, accompanied by some shared expression of concern and regret, plus an assurance that the problem will be rectified, is often all that’s needed to prevent the matter escalating and the patient taking their grievance to a third party.

Unfortunately, with the best will in the world, clear communication sometimes isn’t enough and the motive of revenge or financial gain can mean a practitioner’s reasonable defence falls on deaf ears. When financial compensation is an unlikely outcome, I’ve observed that writing to governing authorities can become the means by which some patients aim to ‘get back’ at the clinician, ‘teaching them a lesson’ and ‘protecting others from harm’.

I’m confident that patients particularly prone to this course of action have an identifiable character profile. Patientes Litigiosum is almost inevitably female and over 50 years of age. Before I’m accused of sexism, my own audit revealed that 90 per cent of our own claimants – those bringing formal suits against my own clinic – were female. This can be explained by the higher percentage of female patients with long-standing prosthodontic issues referred to the clinic. But a review of all our medico-legal referrals to me as an expert witness and involving litigation suits against general dental practitioners over the last three years revealed a 60 per cent female bias.

Figure 1

Issues considered by the GDC’s PCC/PPC in 2015

| ISSUE | NUMBER OF OCCURRENCES** | % OF TOTAL OCCURRENCES |

|---|---|---|

| Poor treatment | 179 | 23% |

| Poor record keeping | 111 | 14% |

| Failure to take appropriate radiographs or to interpret | 80 | 10% |

| Fraud/dishonesty | 53 | 7% |

| Failure to obtain consent/ explain treatment | 42 | 5% |

| Failure to cooperate with the GDC or failure to disclose convictions/cautions | 38 | 5% |

| Personal behaviour | 33 | 4% |

| Prescribing issues | 31 | 4% |

| Working outside scope of practice | 25 | 3% |

| No professional indemnity insurance of failing to produce evidence | 24 | 3% |

| Undiagnosed/untreated caries | 21 | 3% |

| Cross-infection control | 16 | 2% |

| Failings in recording medical and/or dental history | 15 | 2% |

| Conviction or caution – other | 14 | 2% |

| Misleading advertising | 11 | 2% |

| Conviction or caution – assault | 10 | 2% |

| Indecent assault or inappropriate sexual behaviour | 10 | 1% |

| Misled about treatment available on the NHS | 9 | 1% |

| Conviction or caution – alcohol or drugs | 9 | 1% |

| Conviction or caution – theft/robbery | 8 | 1% |

| Failure to refer | 7 | <1% |

| Period of unregistered practice | 5 | <1% |

| Clinically incorrect extractions | 4 | <1% |

| Failure to anaesthetise | 4 | <1% |

| Failure to spot or monitor lesions | 3 | <1% |

| Failure to inform patient of adverse incident | 3 | <1% |

| Employing dentist or nurse not registered with GDC | 3 | <1% |

| Inaccurate statements to CQC | 3 | <1% |

| Tooth whitening | 2 | <1% |

| Making racially offensive comments | 1 | <1% |

| Not supervising Vocational Dental Practitioners adequately | 1 | <1% |

| Total | 775 | |

** Cases often involve more than one issue. These figures provide a profile reflecting the main issues involved, and not every single charge

Our litigant is invariably living alone or estranged from partner or family. If married, their relationships have become unloving and burnt out. It is highly likely they are possessed of a long mental health history of chronic anxiety and depressant illness previously treated with medication and/or cognitive behavioural therapy. Expect a high display of feelings when questioned during a consultation appointment. One will also observe multiple functional disorders, including gynaecological complaints, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and other ailments that long-suffering GPs have failed to ‘put their finger on’. Multiple visits to the GP for exhaustion and irregular sleep patterns are common. The problem for the busy clinician who, understandably, tends to focus on his/ her anatomical area of interest, can easily miss these traits. After all, the dentist is concentrating on the teeth, whereas the orthopaedic surgeon is in ‘bone mode’.

The traditional Western medical approach is collectively disease-focused, whereas the old Greek physician’s philosophy of focusing on “don’t tell me about the disease in the man, but about the man with the disease” could not be closer to the truth. An interview technique that subtly explores the personal, social and professional history is essential in gathering information necessary to the spotting of this high-risk group. Once identified, it then becomes a matter of explaining the interaction of stress and depression upon the immunological competences of a patient, and their ability to cope and heal following stressful surgical assaults. It allows you to share with the patient the responsibility of healing and get them ‘on board’. I have learnt that if a patient can readily connect the dots between their mental and physical health then all is well. However, if the patient vigorously denies any connection between the two, despite it being already abundantly clear, then I consider they’re assuming no responsibility and now refer the patient elsewhere. However, I always pass on this vital piece of information to the referred clinician. Fair’s fair.

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

The logic behind this approach is that I’ve now readily accepted that I cannot possibly connect with all patients all of the time. Where I might fail, another clinician may succeed. By way of an example, a Welsh patient required treatment that she was finding intolerant, and returned repeatedly with bizarre functional symptomology including atypical facial pains and additional locomotor skill loss. A referral to a Welsh consultant did the trick. He carried out a series of placebo adjustments and she reported an extraordinary resolution.

In my opinion, an Englishman was prejudiced from the start, despite the quality of care provided. Incidentally, she had a long history of depressive illness. A useful tool, sadly out of print since 1995 but which I continue to use, is the Cornell Medical Index Questionnaire. This will allow a clinician with no formal training in psychology or psychiatric medicine to identify these patients who often present with multisystem functional disorders.

Having identified the patient traits and context most likely to result in litigation, it seems only fair to consider whether there might be a similar species within the genus Medicus. Is it possible to be more or less prone to action as a practitioner? Although this is wholly anecdotal, I believe that clinicians with OCD characteristics and a liberal sprinkling of Asperger’s make excellent and highly-focused surgeons. But they’re prone to a greater number of complaints when compared with ‘touchy-feely’ clinicians.

Personally, I’d much rather have the indifferent, socially inept OCD character operating on my person than the ‘schmoozer’ who’s more readily distracted by peripheral events. Sadly, as new management practices in the medical arena now demand a more emotional ‘chairside’ manner from our doctors, dentists and surgeons, the public is unaware of what they’re losing. And here’s the rub – for the large part, the rise of the litigious patient helps no-one. The medical profession can maintain the highest possible standards of patient care, but it’s society as a whole that holds blame and scrutiny in balance.

About the author

Toby Talbot is clinical director at the Talbot Clinic. Over the last 17 years, he has established a professional fast-track service for the legal community, helping courts, counsel and judges make accurate and well-informed decisions.

Local anaesthetics interrupt neural conduction by inhibiting the influx of sodium ions through channels within neuronal membranes. When the neuron is stimulated, the channel is activated and sodium ions can diffuse into the cell, triggering depolarisation. Following this sudden change in membrane voltage, the sodium channel assumes an inactivated state and further influx is denied while active transport mechanisms return sodium ions to the exterior.

After this repolarisation, the channel assumes its normal resting state. Local anaesthetics have the greatest affinity for receptors in the sodium channels during their activated and inactivated states rather than when they are in their resting states 1, 2.

Pharmacology

Local anaesthetics consist of three components that contribute necessary clinical properties:

- Lipophilic aromatic ring – improves lipid solubility of the compound

- Intermediate ester/amide linkage

- Tertiary amine.

Articaine consists of an amide group and an ester link. It has a thiophene ring instead of a benzene ring, as seen in the chemical structure of lignocaine. The thiophene ring improves its lipid solubility. Therefore in some studies articaine shows better potential for penetrating through the neuronal sheath and membrane when compared with other local anaesthetics 3.

The dissociation constant of an anaesthetic affects its onset of action. The lower the pKa values, the greater the proportion of uncharged base molecules can diffuse through the nerve sheath. Articaine has a pKa of 7.8, whereas lignocaine has a pKa of 7.9. This proves important when a local anaesthetic is administered to anaesthetise inflamed tissues, where the ph of the tissues is reduced 4. Articaine has a half-life of 20 minutes, whereas lignocaine has a half-life of 90 minutes. Therefore, articaine presents less risk for systemic toxicity during lengthy dental treatments when additional doses of anaesthetic are administered 5.

Comparison between articaine and lignocaine

Some studies argue that there is no significant difference in pain relief provided by 2 per cent lignocaine and 4 per cent articaine where both formulations contain adrenaline 6. However, a recent systematic review demonstrated a different conclusion 7. This review showed that when considering successful infiltration anaesthesia, 4 per cent articaine solution containing adrenaline was almost four times greater than a similar volume of 2 per cent lignocaine also containing adrenaline. Other studies have stated that 4 per cent articaine offers superior levels of anaesthesia in the anterior maxillary region when compared to 2 per cent lignocaine, however this level of superiority appears less significant in the maxillary molar region 8.

There is evidence to support that articaine is more effective in the maxillary posterior region when compared with lignocaine when tissues are inflamed 9. However, there is insufficient evidence to suggest a similar level of superiority for mandibular teeth, where the solution has been administered with the inferior alveolar nerve block technique 10.

The additive administration of lignocaine using the IANB technique and buccal infiltration with articaine could potentially increase the level of pulpal anaesthesia achieved in the mandibular molar and premolar area 11. The inclusion of adrenaline in 4 per cent articaine is considered critical in achieving its profound anaesthesia 12.

Brandt et al demonstrated that articaine was superior when administered using the inferior alveolar nerve block technique (IANB) 7. However, it must be stressed that the potency of the agent administered via the inferior alveolar block was considerably lower than the potency administered by the infiltration technique. It was shown that neither articaine or lignocaine demonstrated superiority over the other when administered to symptomatic teeth. It is important to recognise the limitations in this study of comparing a 4 per cent solution of articaine with a 2 per cent solution of lignocaine 7. Other studies also reported no difference between articaine and lignocaine when using the IANB technique while treating symptomatic teeth 11,13.

Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that 4 per cent articaine with 1:100,000 adrenaline administered using the buccal infiltration technique had a significantly faster onset of pulpal anaesthesia when compared with the inferior alveolar nerve block. Therefore, dentists can consider the use of articaine administered by a buccal infiltration as an alternative to the inferior alveolar nerve block when anaesthetising the mandibular first molar 14. Another study also concluded that articaine delivered by buccal infiltration alone was more effective than lignocaine administered by the inferior alveolar technique when anaesthetising mandibular first molar teeth 15.

Paraesthesia

In 2010, Garisto et al reported 248 cases of paraesthesia after dental treatment 16. Most cases involved mandibular nerve blocks and, in 89 per cent of cases, the lingual nerve was damaged. Paraesthesia was shown to be 7.3 times more likely with 4 per cent articaine when compared with lignocaine. Similar findings were reported by Hillerup et al, who demonstrated greater neural toxicity of 4 per cent compared to 2 per cent articaine. Therefore, it might be advisable to limit the use of 4 per cent articaine to infiltrations and avoid for nerve blocks 17.

Articaine has also been shown to be superior for infiltrations in the mandible and does not cause neural toxicity unless injected near the mental nerve 18.

Paraesthesia has been associated with the use of local anaesthetics, especially when administered using the inferior alveolar nerve block technique 19. Observational research performed in Denmark reported a 20-fold greater risk of nerve injury when articaine was used compared with other local anaesthetics and administered via the IANB technique 17. Given that articaine is less neurotoxic than other anaesthetics, the findings of this research were unexpected 20. It is important to consider that the aetiology of paraesthesia may be the result of a needle injury to the lingual and inferior alveolar nerve. Factors including intra-neural haematoma, extra-neural haematoma, oedema and chemical neurotoxicity of articaine may also play a role 21.

Dentists must also consider the ‘Weber effect’ 22. This occurs when a new product is launched onto the market and is scrutinised more closely. Immediately after 4 per cent articaine containing 1:100,000 adrenaline was introduced, there was a significantly increased incidence of paraesthesia. But, two years later, a reduction was recorded despite an increased number of cartridges being sold 21.

The literature reports that the lingual nerve is more frequently damaged than the inferior-alveolar nerve. Approximately 70 per cent of permanent nerve damage is sustained by the lingual nerve, whereas a 30 per cent occurrence was recorded affecting the inferior alveolar nerve 23. Current data indicates that 85-94 per cent of non-surgical paraesthesia caused by local anaesthetics recovers within two months. After a two month period, two thirds of those patients whose paraesthesia has not resolved will never completely recover 23.

Articaine is also used in areas of medicine such as plastic and reconstructive surgery, ophthalmology and orthopaedic surgery. It is interesting that there are no reports of paraesthesia from articaine following its use in medicine. Is it possible that articaine only affects nerves supplying the oral cavity and specifically the lingual nerve? It is thought that paraesthesia affects the lingual nerve twice as much as the inferior alveolar nerve due to the fascicular pattern of the injection site. Also, when a patient opens their mouth for treatment the lingual nerve is stretched and more anteriorly placed; this decreases its level of flexibility, which is needed to deflect the needle. During administration, the barbed needle can damage the inferior alveolar or lingual nerve during withdrawal 24.

Interestingly, in 2006 – when Hillerup raised concerns that articaine was responsible for neurosensory disturbances – it was found that 80 per cent of all these reports came from Denmark. It is worth noting that, at the time, the Danish population was approximately 5.6 million compared with 501 million in the wider EU community. This research led to the Pharmacovigilance Working Party of the European Union conducting an investigation involving 57 countries and more than 100 million patients treated with articaine. The conclusion was emphatic, stating that all local anaesthetics may cause nerve injury. They estimated that the incidence of sensory impairment following administration of articaine was one in every 4.6 million treated patients. Therefore, no medical evidence existed to prohibit the use of articaine and the safety profile of the drug remained unchanged.

It is worth considering that, before articaine was introduced to the USA, the incidence of permanent nerve damage from inferior alveolar nerve blocks was 1:26,762. In 2007, Pogrel also concluded that nerve blocks can cause permanent damage regardless of which anaesthetic agent is used. Both articaine and lignocaine have been associated with this phenomenon in proportion to their use.

Negative side-effects

Articaine can result in restlessness, anxiety, light-headedness, convulsions, dizziness, tremors, drowsiness and depression 13. Ocular complications have been reported due to interference with sensory and motor pathways 25. Other adverse effects include headaches, facial oedema and gingivitis 13. Skin rashes with itching after administration of articaine have also been cited in the literature 26. Skin necrosis on the chin has also been reported after administration of 4 per cent articaine using the IANB technique 27.

With regards to the cardiovascular system, 4 per cent articaine can decrease cardiac conduction and excitability. Complications such as reduced myocardial contractility, peripheral vasodilation, ventricular arrhythmia, cardiac arrest and, rarely, death have been reported in the literature 28. It is important to exercise caution in patients with severe hepatic impairment. However, the rapid breakdown of articaine into inactive metabolites results in low systemic toxicity 29.

Conclusions on articaine

Since 1973, there have been more than 200 papers published on articaine. Virtually all of these studies have concluded that articaine is as effective and safe as other comparable local anaesthetic agents such as lignocaine, mepivacine or prilocaine. It was shown that articaine is the least likely anaesthetic to induce an overdose caused by administration of too many cartridges. No significant difference in pain relief has been observed between adrenaline containing formulations of 4 per cent articaine and 2 per cent lignocaine.

The time of onset and duration of anaesthesia for 4 per cent articaine is comparable to other commercially available local anaesthetics. Furthermore, the majority of studies have indicated that the incidence of complications including paraesthesia are equal for lignocaine and articaine. The FDA has approved articaine 4 per cent with adrenaline 1:100,000 to age four years in paediatric patients.

The popularity of articaine cannot be disputed within the dental profession. In the USA in 2009, 41 per cent of all dental local anaesthetic used was articaine. In 2012, the market share for articaine in Germany was 97 per cent and in the same year, it was shown that 70 per cent of dentists use articaine in Australia.

Adrenaline-containing anaesthetics

Adrenaline causes constriction of blood vessels by activating alpha-1 adrenergic receptors. It aids hemostasis in the operative field and delays absorption of the anaesthetic. This delayed absorption decreases the risk of systemic toxicity and lengthens its duration of action. Adrenaline can cause considerable cardiac stimulation due to its affect as a beta-1 adrenergic agonist 30.

Cardiovascular influences

Adrenaline is an agonist on alpha, beta-1 and beta-2 receptors. It is a vasoconstrictor as the tiny vessels in the submucosal tissues contain only alpha receptors 31. There is much debate regarding the influence of adrenaline on patients with cardiovascular disease. Dionne et al studied the influence of three cartridges of the American formulation Lidocaine with adrenaline 1:100,000. Submucosal injection of this dosage increased cardiac output, heart rate and stroke volume. Systemic arterial resistance was reduced and mean arterial pressure remained unchanged 32.

Likewise, Hersh et al observed similar results following the administration of articaine containing 1:100,000 and 1:200,000 adrenaline. Although the influence of adrenaline reported by Hersh et al was minor, it is noteworthy that all 14 participants were healthy and taking no medication, yet two of these patients experienced palpitations 33.

A dose of approximately two cartridges of lignocaine containing adrenaline 1:80,000, is the most conservative and frequently cited dose limitation for patients with significant cardiovascular disease. Ultimately, the decision requires the dentist to practise sound clinical judgement and to discuss any concerns with that patient’s doctor if necessary. Peak influences of adrenaline occur within five to 10 minutes following injection and they decline rapidly 33.

Another practical suggestion is to determine the dosage based on patient assessment. If the medical status of a patient is questionable, a sensible protocol is to record baseline heart rate and blood pressure preoperatively and again following administration of two cartridges of lignocaine containing 1:80,000 adrenaline. If the patient remains stable, additional doses may be administered, followed by a reassessment of vital signs 30.

Hypertension

After administering one to two cartridges of adrenaline-containing local anaesthetic with careful aspiration and slow injection and the patient exhibits no signs or symptoms of cardiac alteration, additional adrenaline containing local anaesthetic may be used. A safe option preferred by some dentists is to firstly use a minimal amount of adrenaline-containing local anaesthetic and then supplement as necessary with an adrenaline-free anaesthetic 34.

The risk of the anaesthesia wearing off too soon, resulting in the patient producing elevated levels of endogenous adrenaline because of pain, would be much more detrimental than the small amount of adrenaline in the dental anaesthetic 35.

Drug interactions

Beta-adrenergic blocking drugs increase the toxicity of adrenaline-containing local anaesthetics. It inhibits enzymes in the liver and decreases hepatic blood flow. Therefore, it is advisable not to give large doses of local anaesthetic to patients on beta blockers. There have been multiple reports of stroke and cardiac arrest within the literature 36. Slow administration and aspiration can also help prevent undesirable reactions 37.

Judicious use of adrenaline is recommended for patients medicated with nonselective beta blockers. Unlike selective agents that only block beta-1 receptors on the heart, nonselective agents also block vascular beta-2 receptors. In this case, the alpha agonist action of adrenaline becomes more pronounced and both diastolic and mean arterial pressures can become dangerously increased. This is often accompanied by a sudden decrease in heart rate. Significant consequences of this interaction are well documented 38.

The interaction with beta blockers follows a time course similar to that observed for normal cardiovascular responses to adrenaline. It commences after absorption from the injection site, peaks within five minutes and declines over the following 10-15 minutes. Adrenaline is not contraindicated in patients taking nonselective beta blockers, but doses must be kept minimal and monitoring of blood pressure advisable 39.

Verapamil, which is a popular calcium channel blocker, increases the toxicity of 2 per cent lignocaine. As for patients taking beta-adrenergic blocking drugs, two cartridges should be the limit 40. With regards to bupivacaine, calcium channel blockers enhance the cardiotoxicity of this longer acting anaesthetic 41.

Antihypertensives are the main cardiovascular drugs that interact with anaesthetics containing adrenaline. Theoretically, beta-blockers, diuretics and calcium-channel blockers may all result in adverse reactions when used with adrenaline-containing local anaesthetics 42.

Adrenaline causes alpha and beta-adrenergic agonism. Alpha-adrenoreceptor stimulation results in vasoconstriction of peripheral blood vessels, whereas beta-adrenoreceptor stimulation decreases vascular resistance due to vasodilation of vessels in the liver and muscles, therefore reducing diastolic blood pressure. If beta-effects are blocked, the alpha-adrenergic stimulation leads to an unopposed increase in systolic blood pressure triggering a cerebrovascular accident.

Therefore, if more than one to two cartridges are needed in such patients, adrenaline-free solutions should be administered. An advantage, however, of beta-adrenoreceptor blockers in dental patients is that the heart is protected from the elevation in rate produced by beta-adrenergic stimulation from exogenous adrenaline 43.

Diuretics can affect the metabolic actions of adrenaline. Increased levels of adrenaline reduces the plasma concentration of potassium 44. These reductions have been documented in patients receiving dental local anaesthetics containing adrenaline 45.

In patients undertaking oral surgery procedures who are taking non-potassium-sparing diuretics, there have been incidences of adrenaline-induced hypokalaemia 44. It should remembered that calcium channel blocking drugs may also increase adrenaline-induced hypokalaemia 46.

| AGENT | CONC W/V | CONC MG/ML | MAX DOSE MG/KG | DOSE ML/KG | MG MAX DOSE | CARTRIGES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUPIVACAINE 0.5% | 0.5 | 5 | 1.3 | 0.26 | 90 | 8 |

| LIDOCAINE 2% | 2 | 20 | 4.4 | 0.22 | 300 | 6 |

| MEPIVACAINE 2% | 2 | 2 | 4.4 | 0.33 | 300 | 6 |

| ARTICAINE 4% | 4 | 40 | 7 | 0.18 | 500 | 5 |

| PRILOCAINE 3% | 3 | 30 | 5 | 4.4 | 400 | 6 |

| MEPIVACAINE 3% | 3 | 30 | 4.4 | 0.15 | 300 | 4 |

| PRILOCAINE 4% | 4 | 40 | 5 | 0.13 | 400 | 4 |

| AGENT | CONCENTRATION | TRADE NAME |

|---|---|---|

| BUPIVACAINE | 0.5% | MERCAINE |

| MEPIVACAINE | 2% | LIGNOSPAN |

| LIDOCAINE | 2% | SCANDONEST |

| PRILOCAINE | 3% | SEPTANEST |

| ARTICAINE | 4% | CITANEST |

| MEPIVACAINE | 3% | SCONDONEST |

| PRILOCAINE | 4% | CITANEST |

Angina pectoris and post-myocardial infarction

The use of adrenaline containing local anaesthetics is advisable as part of a stress reduction protocol. The dosage of the adrenaline should be limited to that contained in two cartridges of lignocaine 2 per cent 1:80,000 adrenaline. For patients with unstable angina, a recent myocardial infarction less than six months previously or a recent coronary artery bypass graft surgery within three months warrant all elective dental treatment to be deferred 47. If emergency treatment is imperative, stress-reduction protocols with anti-anxiety agents are advisable with a limitation of two cartridges of adrenaline containing anaesthetic 48.

As part of a stress reduction protocol, the Wand allows the dentist to administer local anaesthetic with a non-threatening handpiece. The anaesthetic syringe is often the principle cause of stress for patients as it is considered by many as the most uncomfortable part of dental treatment. The Wand helps deliver a computer-regulated flow of anaesthetic that enables pain-free dental anaesthesia for the different types of injections. This can help to make the patient less anxious.

Cardiac dysrhythmia

Elective dentistry should be postponed in patients with severe or refractory dysrhythmias until they are stabilised.

It is safe to limit the local anaesthetic dose to two cartridges of lignocaine 2 per cent containing 1:80,000 adrenaline 49. The use of periodontal ligament or intraosseous injections using an adrenaline-containing local anaesthetic is contraindicated 50.

Congestive heart failure

Patients taking digitalis glycosides, such as digoxin, should be carefully monitored if adrenaline-containing anaesthetics are administered as an interaction between these two drugs can trigger dysrhythmias. Patients taking long-acting nitrate medications or taking a vasodilator medication may show decreased effectiveness of the adrenaline and therefore may experience a shorter duration of dental local anaesthesia 48.

Cerebrovascular accident

Following a stroke, it is recommended that dental treatment be deferred due to the significantly elevated risk of recurrence. Following a six-month interval, dental procedures can be rescheduled with the use of adrenaline-containing local anaesthetics. If the stroke patient has associated cardiovascular problems, the dosage of local anaesthetic with vasoconstrictor should be kept to a minimum 48.

Asthma

Stress can precipitate an asthma attack, making stress-reduction protocols essential. Conservative use of local anaesthetics containing adrenaline is advised. The Food and Drug Administration warn that drugs containing sulfites can cause allergic reactions in susceptible individuals 51.

Some studies suggest that sodium metabisulfite, which is an antioxidant agent used in dental local anaesthetic, may induce asthma attacks 52. Data is limited on the incidence of this reaction and even in sulfite-sensitive patients, it appears to be an extremely small risk. Indications are that more than 96 per cent of asthmatics are not sensitive to sulfites and those who are sensitive are usually severe, steroid-dependent asthmatics 53.

Perusse and colleagues concluded that local anaesthetic with adrenaline can be safely used in patients with nonsteroid-dependent asthma. However, until we learn more about the sulfite sensitivity threshold, conservative use of local anaesthetic with adrenaline in corticosteroid-dependent asthma patients is advisable. This is due to their higher risk of sulfite allergy and the possibility that an unintentional intravascular injection might occur, causing a severe asthmatic reaction in a sensitive patient 54. However, in recent times, the results of these older studies have been regarded as questionable by many in the profession.

Hepatic disease

In patients with chronic active hepatitis or with carrier status of the hepatitis antigen, local anaesthetic doses must be kept to a minimum. In patients with more advanced cirrhotic disease, metabolism of local anaesthetics may be significantly slowed, resulting in increased plasma levels and complications from toxicity reactions. Local anaesthetic dosage may need to be decreased and the time lapse between injections extended 55.

Diabetes

Some patients experience dramatic swings between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia and, therefore, the use of adrenaline-containing anaesthetics should be reduced due to the risk of adrenaline-enhanced hypoglycemia 48.

Cocaine

The major concern in patients abusing cocaine is the significant danger of myocardial ischemia, cardiac dysrhythmias and hypertension. Some researchers recommend deferral of dental treatment for 24 to 72 hours 56.

Tricyclic antidepressants

One to two cartridges of adrenaline-containing local anaesthetic can be safely administered to patients taking these drugs. However, careful observation at all times for signs

of hypertension is necessary due to enhanced sympathomimetic effects 57.

HIV

Protease-inhibitor drugs have been shown to increase the plasma levels of lignocaine potentially increasing cardiotoxicity 58.

Parkinson’s disease

Athough there is no data regarding the influence of the anti-Parkinson drug entacapone, caution is advised while using adrenaline-containing anaesthetics. Three cartridges of 2 per cent lignocaine with 1:80,000 adrenaline is the recommended upper limit in adults 59.

Local anaesthetic reversal

A local anaesthetic reversal agent has been introduced that effectively reverses the influence of adrenaline on submucosal vessels. Phentolamine (Ora Verse) is an alpha receptor blocker formulated in dental cartridges 60.

In the future, this may prove useful for some medically compromised patients such as diabetics or elderly patients for whom adequate nutrition may be hindered by prolonged numbness. However, currently this reversal agent is not available in the UK or Ireland.

About the author

Dr Laura Fee graduated with an honours degree in dentistry from Trinity College, Dublin. During her studies, she was awarded the Costello medal for undergraduate research on cross-infection control procedures. She is a member of the Faculty of Dentistry at the Royal College of Surgeons and, in 2013, she completed the Certificate in Implant Dentistry with the Northumberland Institute of Oral Medicine and has since been awarded the Diploma in Implant Dentistry with the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh. Laura is currently completing the Certificate in Minor Oral Surgery with the Royal College of Surgeons, England. She has also been involved with undergraduate teaching in the School of Dentistry, Belfast where she has an honorary oral surgery contract.

References

-

Berde CB, Strichartz GR. Local anesthetics. In: Miller RD, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA et al. Miller’s Anesthesia. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier, Chuchill Livingstone, 2009.

-

Katzung BG, White PF. Local anesthetics. In:Katzung BG, Masters SB, Trevor AJ, editors. Basic and Clinical Phamacology. 11th ed. New York, NY: Mc Graw-Hill Companies Inc; 2009

-

Malamed SF, Gagon S, Leblanc D. The efficacy of articaine: a new amide local anesthetic. J Am Dent Assoc 2000; 131:635-642

-

Kakroudu SHA, Mehta S, Millar BJ. Articaine Hydrochloride: Is it the solution? Dent Update 2015; 42:88-93

-

Becker DE, Reed KL. Essentials of local anesthetic pharmacology. Anesth Prog 2006; 53(3):98-108

-

Malamed SF. The periodontal ligament injection: an alternative to inferior alveolar nerve block. Oral Surg 1982; 53:117

-

Brandt R, Anderson P, Mc Donald N, Sohn W, Peters M. The pulpal anaesthetic efficacy of articaine versus lidocaine in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc 2011; 142(5):493-504

-

Yapp K, Hopcraft M, Parashos P. Articaine: a review of the literature. Br Dent J 2011; 210:323-329

-

Srinivasan N, Kavitha M, Longanathan C, Padmini G. Comparison of the efficacy of 4% articaine and 2% lidocaine for maxillary buccal infiltrations in patients with irreversible pulpitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009; 107: 133-136

-

Claffey E, Reader A, Nusstien J, Beck M, Weaver J. Anaesthetic efficacy of articaine for inferior alveolar blocks in patients with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod 2004; 30:568-571

-

Kanaa MD, Whitworth JM, Corbett IP, Meechan JG. Articaine buccal infiltration enhances the effectiveness of lidocaine inferior alveolar nerve block. Int Endod J 2009; 42: 238-246

-

Moore PA, Boynes SG, Hersh EV, De Rossi SS, Sollecito TP, Goodson JM, Leonel JS, Flores C, Peterson C, Hutcheson M. The anesthetic efficacy of 4% articaine 1:200,000 epinephrine: two controlled clinical trials. J Am Dent Assoc 2006; 137:1,572-1,581

-

Septodont Inc Septocaine(articaine hydrochloride 4% with epinephrine 1,100,000) injection prescribing formulation. Manufacturer’s Drug Information Leaflet.

-

Jung IY, Kim JH, Kim ES, Lee CY, Lee SJ. An evaluation of buccal infiltrations and inferior alveolar nerve blocks in pulpal anesthesia for mandibular first molars. J Endod 2008; 34: 11-13

-

Corbett IP, Kanaa MD, Whitworth JM, meechan JG. Articaine infiltration for anesthesia of mandibular first molars. J Endod 2008; 34: 514-518

-

Garisto GA, Gaffen AS, Lawrence HP, Tenenbaum HC, Haas DA. Occurrence of paresthesia after dental local anesthetic administration in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010; 141:836-844

-

Hillerup S, Jensen RH, Ersboll BK. Trigeminal nerve injury associated with injection of local anesthetics: needle lesion of neurotoxicity. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:531-539

-

Robertson D, Nusstein J, Reader A, Beck M, Mc Cartney M. The anesthetic efficacy of articaine in buccal infiltration of mandibular posterior teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007; 138:1104-1112

-

Haas DA, Lennon D. A 21 year retrospective study of reports of paresthesia following local anesthetic administration. J Can Dent Assoc 1995;61:319-330

-

Werdehausen WR, Fazeli S, Braun S, Hermanns H, Essman F, Hollman MW, Bauer I, Stevens MF. Apoptosis induction by different local anaesthetics in a neuroblastoma cell line. Br J Anaesth 2009; 103: 711-718

-

Haas DA. Localized complications from local anesthesia. J Calif Dent Assoc 1998; 26:677-682

-

Hartnell NR, Wilson JP. Replication of the Weber effect using postmarketing adverse event reports voluntarily submitted to the United States Food and Drug Administration. Pharmacotherapy 2004; 24:743-749

-

Pogrel MA, Schmidt BL, Sambajon V, Jordan RC. Lingual nerve damage due to inferior alveolar nerve blocks: a possible explanation. J Am Dent Assoc 2003; 134: 195-199

-

Stacey GC, Hajjar G. Barbed needle and inexplicable paraesthesias and trismus after dental regional anaesthesia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994; 77:585-588

-

Penarrocha-Diago M, Sanchis- Bielsa JM. Opthalmologic complications after intraoral local anesthesia with articaine. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000; 90:21-24

-

Malanin K, Kalimo K. Hypersensitivity to the local anesthetic articaine hydrochloride. Anesth Prog 1995; 42:144-145

-

Torrente-Castells E, Gargallo- Albiol J, Rodriguez- Baeza A, Berini-Aytes L, Gay- Escoda C. Necrosis of the skin of the chin: a possible complication of inferior alveolar nerve block injection. J Am Dent Assoc 2008; 139:1,625-1,630

-

Elad S, Admon D, Kedmi M, Naveh E, Benzki E, Ayalon S, Tuchband A, Lutan H, Kaufman E. The cardiovascular effect of local anesthesia with Articaine plus 1:200,000 adrenaline versus Lidocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenalin in medically compromised cardiac patients: a prospective randomized double blinded study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008; 105:725 -730

-

Oertel R, Rahn R, Kirch W. Clinical pharmacokinetics of articaine. Clin Pharmacokinet 1997; 33; 417-425

-

Becker DE, Reed KL. Local Anesthetics: Review of Pharmacological Considerations. Anesth Prog. 2012 Summer; 59(2): 90-102

-

Westfall TC, Westfall DP. Adrenergic agonists and antagonists. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC, editors. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. New York, NY: Mc Graw-Hill Companies Inc; 2011

-

Dionne RA, Goldstein DS, Wirdzek PR. Effects of diazepam premedication and epinephrine-containing local anesthetic on cardiovascular and catecholamine responses to oral surgery. Anesth Analg. 1984; 63:640-646

-

Hersh EV, Giannakopoulos H, Levin LM et al. The pharmacokinetics and cardiovascular effects of high-dose articaine with 1:100,000 and 1:200,000 epinephrine. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1562-1571

-

Schecter E, Wilson MF and Kong, YS, Physiologic responses to epinephrine infusion: the basis for a new stress test for coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 105:554-60, 1983

-

Dimsdale JE, Moss J. Plasma catecholamines in stress and exercise. J Am Med Assoc 1980; 243:340-2

-

Gandy W. Severe epinephrine-propranolol interaction. Ann Emer Med. 1989;18:98-99

-

Malamed SF, Handbook of Dental Anesthesia, Elsevier Mosby, St Louis Mo, USA, 5th edition, 2004

-

Doman S. An audit of the use of intra-septal local anesthesia in a dental practice in the South of England. Prim Dent Care 2011; 18: 143-147

-

Godzieba A, Smektala, Jedrzejewski M, Sporniak-Tutak K. Clinical Assessment of the safe use local anaesthesia with vasoconstrictor agents in cardiovascular compromised patients: A systematic review. Med Sci Monit. 2014; 20: 393-398

-

Tallman RD, Rosenblatt RM, Weaver JM, Wang YL. Verapamil increases the toxicity of local anesthetics. J. Clin Pharmacol 1988 Apr; 28(4): 317-21

-

Adsan H, Tulunay M, Onaran O. The effects of verapamil and nimodipine on bupivacaine-induced cardiotoxicity in rats: as in vivo and in vitro study. Anesth Anal 1998 April; 86(4): 818-24

-

Becker DE. Adverse drug interactions. Anesth Prog. 2011; 58:31-41

-

Foster CA, Aston SJ. Propranolol-epinephrine interaction: a potential disaster. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983; 72: 74-78

-

Struthers AD, Reid JL, Whitesmith R, Rodger JC. Effect of intravenous adrenaline on electrocardiogram, blood pressure and serum potassium. Br Heart J 1982; 49: 90-93

-

Meechan JG, Rawlins MD. The effect of adrenaline in lignocaine anaesthetic solutions on plasma potassium in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1987; 32: 81-83

-

Mimram A, Ribstein J, Sissman J. Effects of calcium channel blockers on adrenaline- induced hypokalaemia. Drugs 1993; 46(Suppl 2): 103-107

-

Peruse R, Goulet JP, Turcotte JY. Contraindications to vasoconstrictors in dentistry: Part 1, cardiovascular diseases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992, 74:679-86

-

Little JW, Falace DA et al. Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patients, 5th ed. Mosby – Year Book, St Louis, 1997

-

Becker DC, Drug interactions in dental practice: a summary of facts and controversies. Compend Cont Educ Dent 1994, 15:1228-44

-

Muzyka BC. Atrial fibrillation and its relationship to dental care. J Am Dent Assoc 1999, 130: 1080-5

-

United States Department of Health and Human Services: Warning on Prescription Drugs Containing Sulfites, FDA Drug Bull, 17: 2-3, 1987

-

Seng GF, Gay BJ. Dangers of sulfites in dental local anesthetic solutions: warning and recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc 1986, 113: 769-70

-

Bush RK, Taylor SL et al. Prevalence of sensitivity agents in asthmatic patients. Am J Med 1986, 81:816-20

-

Perusse R, Goulet JP, Turcotte JY. Contraindications to vasoconstrictors in dentistry: Part II, hyperthyroidism, diabetes, sulfite sensitivity,cortico-dependent asthma and pheochromocytoma. O Surg O Med O Path 1992, 74: 687-91

-

Demas PN, JR Mc Clain. Hepatitis: implications for dental care. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 88(1):2-4, 1999

-

Yagiela JA. Adverse drug interactions in dental practice: interactions associated with vasoconstrictors. J Am Dent Assoc 1999, 130:701-9

-

Goulet JP, Perusse R, Turcotte JY. Contraindications to vasoconstrictors in dentistry: Part III, pharmacologic interactions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992 74:692-7

-

Greenwood I, Heylen R, Zakrzewska JM. Anti-retroviral drugs – implications for dental prescribing. Br Dent J 1998; 184:478-482

-

Friedlander AH, Mahler M, Norman KM, Ettinger RL. Parkinson disease: systemic and orofacial manifestations, medical and dental management. J Am Dent Assoc 2009 Jun; 140(6): 658-69

-

Moore PA, Hersh EV, Papas AS et al. Pharmacokinetics of lidocaine with epinephrine following local anesthesia reversal with phentolamine mesylate. Anesth Prog. 2008; 55:40-48

There is no doubt that dentistry is a high-stress profession. Recent studies have reported that dental teams are subject to a variety of stress-related physical and emotional problems 1,2,3,4. These include heart disease, high blood pressure, adrenal fatigue, alcoholism, insomnia, depression and anxiety 5. Stress can be defined as ‘‘an adverse reaction that people have to excessive pressure or other types of demand placed on them’’.

Research suggests that the top five stressors in dentistry include running behind schedule, causing pain to our patients, heavy workloads, patient management and the treatment of anxious patients 2. As well as these factors, we have litigation on the increase 6 (the UK has now taken over the US with regards to litigation cases), and the GDC’s Fitness to Practise committees to worry about. When you take all of these factors into account, it is unsurprising that stress levels in dentistry are soaring to dangerously high levels. Yet, there is a lack of proactive measures being taken within our working environment and teams to address this issue of stress.

The signs of stress in an individual include feeling tense, feelings of anger and frustration, worry and anxiety, lack of concentration at home and at work, impaired sleep, depression, lack of interest in hobbies, poor appetite, comfort eating, increased consumption of alcohol and other stimulants to help to cope with the emotional impacts of stress. This can manifest within the dental team in many ways which include conflict within the team, absenteeism, a high turnover rate in staff, low morale, increased complaints, poor performance while at work and at times a lack of care in the standard of treatment provided. It is not only in the workplace that the effects of stress can manifest. They can also be present in the home and can cause problems with personal relationships. So, as there is no doubt that dentistry is a high-stress profession, what steps can we take within the dental team to prevent this?

We are regularly given advice on how to lead healthy lives, but sometimes we are so caught up in the stresses of life and work that we don’t know how or where to begin. I frequently hear colleagues suffering with stress say that they do not have time to fit exercise and attending the gym into their life due to their workload, commuting and their family commitments. It is only when they reach near-breaking point with their stress levels that they consider introducing some form of stress management into their life. I prefer a more preventive approach with stress involving a combination of regular physical exercise and well being activities such as yoga or tai chi.

I have been practising yoga for more than 15 years; initially it was the only type of exercise that I felt completely relaxed afterwards. I could go into a yoga session completely wired after a stressful day and come out the class an hour later in a blissful state. After a while I started to realise, though, that this blissful state would only last for a few hours after the yoga class or if I was lucky maybe 24 hours, and then the stress levels would rise again. What I realised was that if I made time to meditate every day in between the yoga classes I could return to the relaxed state that I had experienced quite easily to keep me going to my next class.

Meditation is an easy stress-management tool, which can be incorporated into your daily life very easily. When an individual is stressed, it is the sympathetic nervous branch of the autonomic nervous system that becomes overloaded. This is our ‘fight or flight’ response. The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) stimulates the adrenal glands when we are in flight or flight mode, releasing adrenaline and noradrenaline. This increases our heart rate, our blood pressure and our breathing rate. Once activated it can take anything from 20-60 minutes to return to pre-stimulation rates. By meditating and focusing on our breath we can turn off the SNS and switch on the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), which is known as the ‘rest and digest’ response. When the PNS is activated, our heart rate drops, our blood pressure falls, our muscles relax and our breathing slows and deepens.

A practice of daily meditation can make our minds calm and peaceful, allowing us to take a step back from the hectic lives we are all leading. The more we incorporate it into our daily lives the more peaceful our minds become, the less stress our bodies have to cope with and we become happier in both our professional and personal lives.

Meditation is not a complicated practice; all we basically need to do is focus our minds. It can be done anywhere and at anytime, and the results can be seen very quickly by the individual. For me, I find that spending my last 15 minutes of my lunch hour sitting on my dental chair meditating is the time I can fit my daily meditation routine in. Of course, in order to be able to achieve this I have to be organised with taking my lunch to work with me everyday, either preparing my lunch the night before or purchasing it on the way to work in order to give me the time during my lunch break to meditate. When I first started to do this at lunchtime, no one actually knew what I was doing in my surgery. I think everyone thought I was sat relaxing listening to music on my iPhone!

How to begin meditating

The practice is a very simple one. I would suggest you find a quiet space and sit down. You can sit normally on a chair or sit on your dental chair, being comfortable with a straight back is the main aim. Keeping your eyes open initially, bring your focus onto your breathing. I like to do a three-part breath, that is taught in yoga, to initially calm my breathing down. I breath into my stomach, rise the breath into my chest and feel my back expand and then feel my collar bones rise. To exhale I lower the collar bones, deflate my chest and pull in my stomach gently squeezing the last of the breath. I repeat this for a few minutes, then I close my eyes.

Depending on how my mind is on the day will determine what I focus on during my meditation. My mind will vary from day to day like any other mind. What I have found that really helps me to deal with all of my thoughts is to accept and acknowledge that, once my meditation is over, I will be able to get to them, and that the time I allocate for meditation is just for that. Everything will be still be there in 15 minutes when I start work again. Meditation is the process of getting to know our mind and understand it. The trick is not to identify with your thoughts and give them any energy or focus, just observe them.

Once my eyes are closed I continue with my breathing and do a mental scan of my body to see where any tension may be. Working my way from my head down to my toes I relax any tension that I have in my body, and then return my focus to my breath. Any thoughts that come into my head I let come and go, observing them without feeding into them. At this point my mind starts to settle fully and becomes peaceful.

This is the parasympathetic nervous system switching on and starting to do all of the good work in getting you back to feeling human again. I like to stay in this headspace with my eyes closed for as long as I can, at least 10 minutes. I use an app on my phone to time this, which really helped in the beginning as it stopped me worrying about how long I was sitting there for.

When my mediation time is up, I open my eyes and carry on with my working day. It is now part of my daily working routine, which I look forward to each day.

Guided meditation

If you find that the breathing meditation does not work for you in the beginning you can try a guided mediation. This is a when you are guided into a relaxed state by a teacher or trained practitioner. There are many of these available in app form and also free on YouTube.

Mantra meditation

This is the practice of repeating a mantra over and over in your mind during your meditation. It is a really good method of meditation for beginners as it really helps to focus your mind on the words that you are saying, giving a distraction from your thoughts. The mantra can be anything you want, from a positive affirmation of ‘I change my thoughts, I change my world’ to using a Hindu mantra, an example being a simple ‘Om’ or ‘Om Namah Shivaya’ or just a simple phrase or word like relax or peace.

Yoga and meditation

You gain the most benefit from your meditation when combining it with a yoga practice. Yoga has the ability to trigger both the SNS and the PNS, and is designed, when practised in its traditional form, to prepare you for meditation. A good rounded yoga class will trigger the SNS at the beginning of the class with sun salutations and more challenging postures then introduce postures that trigger the PNS such as seated forward bending postures and shoulder stands (these can be easily done by beginners by placing their legs up against a wall with their back staying flat on the floor), before taking you into yoga nidra which is the deep relaxation at the end of a yoga class, which stimulates the PNS further. This is followed by some breathing exercises, or pranayama as it is called in yoga, to help prepare your mind further for the meditation at the end of the class, which again stimulates the PNS further.

Apps to help with meditation

There are many apps available either free or at a small cost to help you with your meditation. I find that these can be really helpful with introducing a new habit or routine. As with any form of behaviour change it is forming a good habit and getting into a good routine that will ensure you keep the daily practise going. The apps monitor your progress and help with the formation of new habits with different methods of reinforcement.

- Headspace (Fig 1)

Headspace is an app that has 10 free introductory sessions before requiring you to subscribe. It is available from the app store and is a good way to introduce meditation into your daily routine. It records your progress with each session building on the last. If you subscribe, there are sessions available to help with many different topics from depression to over eating. - Insight (Fig 2)

The Insight timer is another app available from the app store. It is a timer for your meditation where you can determine the length of time you would like to meditate for. It is also has a great resource of guided meditations available free on topics including an introduction to meditation, morning meditations, sleep meditations, relaxation, mindfulness, self love and compassion and a collection of talks and podcasts. - Oprah and Deepak’s 21-day meditation (Fig 3)

Oprah Winfrey has teamed up with Deepak Chopra, introducing a free 21-day mediation course at different times throughout the year. There are 21 daily downloads of meditation and wisdom from Deepak and Oprah, with each day building on the previous day’s session. If you miss the sign-up for this programme you can purchase it from their website www.chopracentremeditation.com

Alternatively you can visit Deepak’s own website – www.deepakchopra.com – which is a great resource for information on meditation including many free downloads. - Breathe (Fig 4)

This app monitors your progress and also has a range of free guided meditations. It is designed to reinforce behavioural change and habits with rewarding you with different stickers when you have completed any of the goals that are set for you by the app.

- Figure 2 – Insight timer app

- Figure 3 – Oprah and Deepak’s 21-day meditation app

- Figure 4 – Breathe app

Conclusion

Dentistry is a high-stress profession, not just for the dentist but also for each member of the team. If we do not manage our stress levels effectively, eventually we will become demotivated, burn ourselves out and put ourselves at risk of stress-related illnesses. Forming a good habit of taking a time out of 10-15 minutes each day to relax and refocus can help to reduce stress levels of all members of the team.

About the author

Morag has been involved in the dental industry for 25 years. She is dually qualified, as a hygienist and a therapist, with a primary focus on delivering high-quality dental care in private practice. She has a special interest in adult periodontics, peri-implantitis and composite restorations.

An advocate of lifelong learning, she has recently completed the BSc (Hons) course in Dental Studies at UCLAN. Prior to relocating to Gibraltar, Morag ran a study club for hygienists and therapists in the north of Scotland, delivering education to local colleagues. Morag is also a consultant for the Swiss dental instrument company Deppeler and a tutor for Aspiradent, a postgraduate teaching company.

Working as lead hygienist therapist at Fergus & Glover, Morag led the team to win the ‘Best Preventive Practice’ in the UK at the DH&T awards 2012, and has been shortlisted for both Hygienist of the Year at the DH&T awards and DCP of the Year at the Scottish Dentistry awards.

References

1. R. Rada, C. Johnson-Leong. Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among dentists. The Journal of the American Dental Association. June 2004, Vol. 135(6): 788-794, doi: 10.14219

2. J. Ayatollahi, F. Ayatollahi, M. Owlia. Occupational hazards to dental staff. Dental Research Journal. Jan-Mar 2012:9(1):2-7

3. A. Puriene, V Janulyte, M. Musteikyte, r. Bendinskaite. General health of dentists – Literature review. Baltic Dental and Maxillofacial Journal. 2007, 9:10-20

4. H. Myers, L. Myers. ‘It’s difficult being a dentist’: stress and health in the general dental practitioner. Br Dent J. 2004. Jul 24;197(2):89-93

5. J. Lang. Stress in dentistry – it could kill you! Oral health. Available from: http://www.oralhealthgroup.com/features/stress-indentistry-could-kill-you/ .(Accessed June 2016)

6. J. Hyde. ‘Unprecedented’ clinical negligence claims as PI firms migrate. The Law Society Gazette. July 2014

Depending on what you read, there are various criteria proposed for assessment of endodontic outcome and these differ depending on whether a surgical or non-surgical approach has been used. The European Society of Endodontology proposes the following definition of non-surgical root canal treatment (NSRCT) outcome:

- Healed: Absence of clinical signs and symptoms and a return to normal architecture of the periodontal ligament radiographically.

- Healing: Absence of clinical signs and symptoms and reduction in size of the periapical lesion.

- Failure: Presence of clinical signs/symptoms and/or no reduction in lesion size, increase in lesion size or emergence of a new periapical lesion.

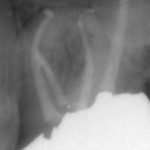

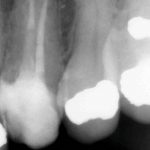

From the literature, it would seem that success rates of NSRCT are relatively high depending on the criteria used yet often teeth exhibiting reduced lesion size are hard to classify. Although Orstavik (1996) highlighted that teeth showing these radiographic signs of healing at 12 month review, continue to heal in almost 90 per cent of cases (Figs 1a and b). For those dubious cases it is important to arrange follow up for anything up to four years and not condemn a tooth to failure too early (Strindberg 1956).

Does survival count?

The stringent outcome criteria outlined above have been used to assess NSRCT for decades. More recently, however, survival rates have been mentioned in the endodontic literature (Salehrabi 2004).

This has partly been driven by the endodontic discipline in order to level the playing field between endodontics and implants. Much of the implant literature uses this less stringent definition of treatment outcome, with survival rates in excess of 90 per cent being reported. The reality is that it is very difficult to compare the two treatment modalities and unnecessary also as both have a place in daily practice life. Direct comparisons, although shining a favourable light on endodontics (Doyle 2006) are also confusing and probably best avoided.

More recently, the term functionality has appeared in the endodontic literature and this may be more relevant to practice. Friedman (2004) described this as a tooth presenting with an absence of clinical signs/symptoms but with evidence of pathosis radiographically. How often do we see patients who, when faced with the prospect of dismantling a tooth which has been in function for decades and exposing themselves to the risk of it being unrestorable, choose to continue to monitor the situation instead? This may pose problems later in terms of potential flare up and possible systemic impacts of oral infection although the evidence supporting the later in the endodontic literature is scarce.

Are cracked teeth doomed to failure?

Diagnosis of and prognostication in relation to cracked teeth is difficult. Where does the crack end? How likely is it to progress? Will it affect longevity? All of these questions spring to mind when we consider this clinical scenario.

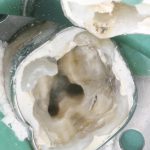

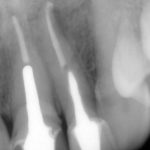

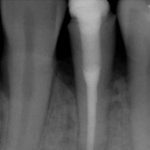

Patients presenting with symptoms of a crack in a vital tooth should always be investigated thoroughly and this often involves removal of the direct restoration, visualisation of the crack under magnification and illumination and possibly a period of stabilisation with a stainless steel orthodontic band. In the cases of root filled teeth, again the tooth should be dismantled and the crack visualized in order to attempt to assess its severity (Figs 2a-c). Care should also be taken to identify and assess any soft tissue signs such as multiple draining sinuses or deep narrow isolated probing defects adjacent to heavily restored root filled teeth. Cracks can often be very difficult to diagnose radiographically unless there is frank separation of the tooth fragments although a characteristic J-shaped radiolucency may indicate a split tooth.

The American Association of Endodontists (AAE) have attempted to classify cracked teeth according to severity, ranging from an enamel infraction up to a split tooth and this is helpful in terms of reaching a diagnosis and labelling these teeth. It does not, however, offer much help in terms of deciding on whether to treat or extract these teeth. Traditionally, it was felt that the presence of a crack on the floor of the pulp chamber often precluded endodontic treatment, but more recent outcome studies have highlighted the importance of the presence of a deep probing defect associated with the tooth as a negative prognostic factor (Tan et al. 2006, Kang et al. 2016) while others have found that extension on to the pulpal floor resulted in greater tooth loss (Sim et al. 2016). So, that just seemingly adds to the confusion.

Most importantly, the patient needs to be made aware of the presence of a crack and its potential effect on outcome. Ultimately, it is the patient who decides, although I would personally caution against attempting to save teeth with extensive cracks due to the detrimental effect this would have on the surrounding bone should the crack propagate and the subsequent effect on the bony site for implant placement.

Does rubber dam actually matter?

Although the use of rubber dam is widely recommended during endodontic treatment, two things become clear when the evidence is examined more closely:

- Rubber dam is not routinely used during treatment. According to Whitworth et al. (2000), 60 per cent of dentists never use it, with factors such as patients’ perceptions, time to apply and a lack of training being cited as obstacles.

- There is actually very little in the literature which highlights the positive impact rubber dam use can have on the outcome of endodontic treatment, with only van Nieuwenhuysen et al. (1994) and Lin et al. (2014) showing a positive association.

However, this should not mean that we do not recognise the multiple benefits of rubber dam use during endodontic treatment, namely retraction of soft tissues, better visualisation and protection of the airway among them. The reality is that rubber dam makes our job easier and that makes a difference (Fig 3).

What effect do missed canals have?

Uninstrumented and unfilled root canal anatomy can clearly have an effect on endodontic outcome, and nowhere is this more evident than in the case of the second mesiobuccal canal or MB2 in maxillary molars.