There are four main domains where the workings of the mind have had an influence on our daily practice. These are: the dentist-patient relationship, dental anxiety, chronic oral facial pain and the stress of dental practice. In this article, I will address the first two domains and suggest ideas as to how both patients and the dental team would be better served by a more holistic body mind paradigm. In the next issue, I will discuss the final two influences. The duality of mind and body, first advocated in the 17th century by René Descartes, is finally beginning to find a home in Western medicine.

The influence of the mind on the development and progress of disease, both physical and psychological, is receiving the research attention that it merits. Descartes postulated that there was a real distinction between the immaterial mind and the material body. Although mind and body are ontologically distinct substances, they causally interact.

Psychology is defined in the Oxford dictionary as the scientific study of the human mind and its functions, especially those affecting behaviour. The etymology of the word is from modern Latin meaning the study of the soul. The history of psychology dates back to the Ancient Greeks who regarded it as a philosophy rather than a science. It was not until the late 1800s that it developed into a scientific subject.

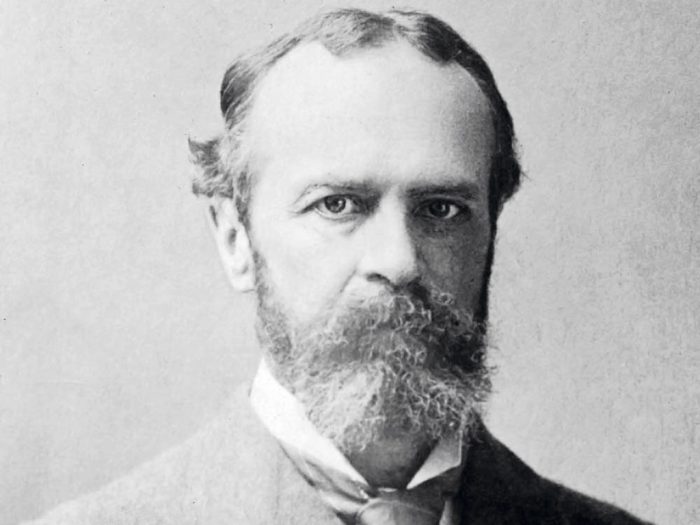

The first psychology lab was at the University of Leipzig where Wilhelm Wundt studied reaction times. The father of American psychology was William James who wrote The Principles of Psychology and was interested in conscious human experience. The dichotomy of thought in psychology made its appearance in Austria around the same period, with the work of Sigmund Freud on the unconscious. His psychoanalytic theory arose from work with hysterical patients were he proposed the unquiet mind derived from unresolved childhood conflicts.

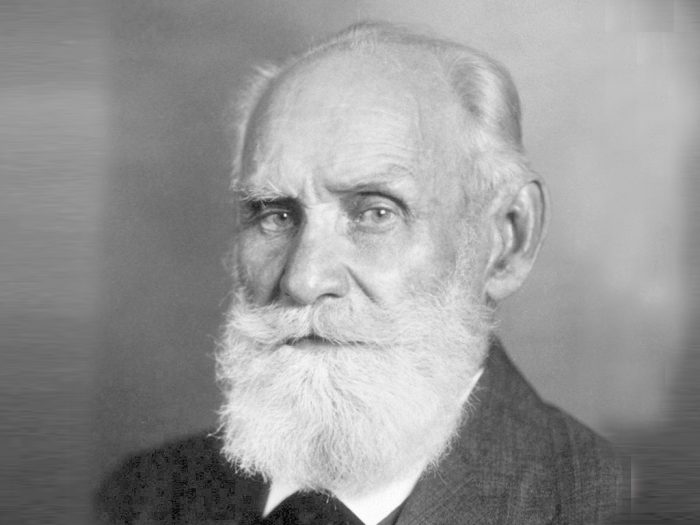

The work of the Russian psychologist Ivan Pavlov heralded in the age of behaviourism, his most famous experiment being Pavlov’s dogs showing classical conditioning. This was soon followed by Skinner and operant conditioning looking at behaviour in terms of actions and consequences. Carl Rogers’ theory gave birth to the third force in psychology known as humanistic psychology. It emerged as a paradigm to counteract the limitations of behaviourism and psychoanalysis.

Psychologists such as Rogers and Maslow were interested in the meaning and purpose of human behaviours. They were fascinated as to what conditions fostered the growth of the human person to self-actualise within the constraints of their own environment. The term cognitive psychology was first used by Ulric Neisser in 1967 and is a branch of psychology which is goal orientated and problem focused. The three main therapies arising from this way of thinking are:

- Albert Ellis’s rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT)

- Aaron Beck’s cognitive therapy (CT)

- Donald Meichenbaum’s cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)

The main principles under lying these therapies were first voiced by William James at the beginning of the 20th century: “Thoughts become perception, perception becomes reality. Alter your thoughts, alter your reality.”

Today, psychology is very much rooted in neuroscience and neurobiology. The advent of magnetic resonance imaging has provided a non-invasive way of examining the human brain. The amygdala, hippocampus, and medial prefrontal cortex have been shown to be involved in the stress response and in PTSD. Research in this domain is bringing understanding as to how therapies like eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) and brainspotting might work.

This brief introduction serves to demonstrate the plethora of knowledge that seeks to understand the human mind and human behaviour. The richness of psychological knowledge permeates into every area of society yet the primacy of this way of thinking is sometimes overlooked in the reductionist materialistic way that we teach our medical and

dental students.

Dentist-patient relationship

The work of Mills et al (2015) attempts to classify the main indicators of a good patient experience. In the UK, the NHS Patient Experience Framework highlights the Picker Principles of Patient-Centred Care as the optimum way to provide care. This form of care embraces much more than the daughter test as it invites us to see the other through the lens of compassion.

Patient-centred patient care has evolved from the philosophy of the humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers. Rogers believed that the patient is the expert in their own lives and, if given the opportunity, will self-actualise within their own environment. He used the metaphor of a potato in a darkened room sending out shoots towards a crack of light. If a patient is treated with empathy, unconditional positive regard and congruence within the dental domain then the framework for a positive patient experience is put in place.

This is fine rhetoric but words have no value unless they can be put into action. The following narrative, although not based in the dental surgery, involved a patient who sadly was in the end stages of oral cancer. His name has been altered to protect his identity. Many years ago, I had recourse to visit this man – let’s call him Bob – in hospital, he was dying from the ravaging effects of oral cancer. He was being fed through a peg tube and his breathing eased by a tracheostomy. This gentleman had been a rough sleeper for most of his life and had enjoyed solace from a homeless centre where I worked. On visiting him in his hospital room I brought him shower gel and soap to which he promptly replied: “What the hell are you bringing me these for? I need Guinness and fags!”

On exiting the room I put this request to the nursing sister; she looked at the patient and then myself and said to bring him some Guinness and some fags. On my next visit, I watched Bob syringe the Guinness into his peg tube and smoke his cigarette through his tracheostomy.

That nurse had treated Bob as a human being, she had given him dignity and respect. This man had lived on the streets where alcohol and cigarettes, for whatever reason, had been his only consolation. At this end stage of his life the nurse had looked on him with empathy and unconditional positive regard and bestowed upon him the dignity of being permitted to die with the tools that had enabled him to live. She, within the limits of her environment, had not allowed rigid protocols to undermine the humanity of the other.

Empathy and unconditional positive regard in the dental surgery invites us to treat others as we would like to be treated ourselves. It does not judge or stereotype our patients but treats each individual as unique. In this uniqueness, the encounters with our patients hold the potential of enriching both our lives and the life of the other. In my experience, kindness is the medium through which empathy is conveyed to the patient. Unconditional positive regard is the prising of the other for no other reason than they are our fellow travellers on this earthly sojourn. To hold the other in a positive light is to convey to them that they matter, they are not simply another extraction or a bridge to be fitted. They too have a place in society and their wellbeing is of prime importance to us.

The research of Sherman at the University of Washington Dental school shows that there is a decrease in clinical empathy over the four-year training course. This mirrors the work done by Chen (2012) on medical undergraduates. Research demonstrates that students who have a high level of empathy are more competent at history taking, have a higher physician and patient satisfaction, decreased malpractice litigation and are significantly better at motivating patients.

The importance of empathy in health care was emphasised in the Francis Report after the systemic failings at the Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust. The GDC in their Preparing for Practice document highlight the importance of communication and professionalism in the training of undergraduates. Much research is needed in defining clinical empathy and discovering how best it may be taught.

Dental anxiety

The 2009 Adult Dental Health Survey, commissioned by the NHS Information Centre, revealed that 36 per cent of adults had moderate dental anxiety and 12 per cent were classified as being dentally phobic managing their anxiety by avoidance of all things dental. The impact of dental anxiety can have far-reaching consequences on a patients health and wellbeing, both psychologically and physically. Yet the literature reveals that there are no specific guidelines on the diagnosis or treatment of dental anxiety.

The work of Professor Tim Newton of King’s College London Dental Institute, Health Psychology Service and Art De Jongh of the Netherlands go along way to address this. Both authors offer a framework in which to classify dental anxiety and suggest different treatment modalities dependent of the level of anxiety. They propose that mild dental anxiety can and should be treated in the dental surgery by the dental team.

Research reveals that good interpersonal skills and empathy can of themselves decrease dental fear. Good communication enables the establishment of trust and a framework in which to carry out treatment. Precise information regarding the exact nature of treatment is essential to allay fears as is the establishing of a sense of control by adopting a stop signal. The “tell, show, do” technique has been about for more than 50 years and can be used for the simplest to the most complex treatment. There is also a place for the consideration of premedication and the use of nitrous oxide. The use of coping strategies such as distraction through visual or auditory stimuli and relaxation techniques all have part to play in mild dental anxiety management.

Hypnosis was first used in 1841 by the English physician James Braid and has been used in dentistry for well over half a century. It is a non-pharmacological method of inducing a trance-like state. In this state of altered consciousness, the patient is able to focus all of their attention on an image, thought or feeling and in so doing take their attention away from their feelings of anxiety. This method can also be very helpful in treating an overactive gag reflex, which is often found in dentally anxious patients. In order to aid the dental team in their treatment of patients with mild to moderate anxiety the website dentalfearcentral.org is an excellent resource for both staff and patients.

Patients who present with a moderate to severe level of dental anxiety should, in many cases, be referred to a secondary centre for the treatment of their dental anxiety. This secondary centre could be managed by a psychologist or a dentist with psychotherapy training (generic training or CBT training). The reason for this referral would be to assess the level of dental anxiety and also determine if there are any co-morbid psychological conditions.

In research done at Kings by Kani et al (2012), 37 per cent of the patients who had dental phobia were also shown to have high levels of generalised anxiety, 12 per cent had clinically significant depression and 12 per cent were shown to have suicide ideation. A referral centre that would enable assessment of dentally anxious patients would compliment a sedation service and offer patients definitive tailored treatment to address their dental anxiety.

A study done by Woolley in 2009 showed that individuals who are referred for sedation are highly anxious and fear a range of different dental stimuli. Yet previous research demonstrated that referring dentists to a sedation clinic did not consider psychological management for their patients. Sedation has, and always will have, a part to play in the management of dental anxiety but the only way to address the underlying issues is to complement the service with psychological interventions.

The study conducted by Kani et al (2012) showed that, of the 130 dentally phobic patients referred to the King’s College London Dental Institute, 79 per cent went on to have dental treatment without sedation. These patients were treated by CBT. This therapy has proven efficacy for the management of anxiety and depression. CBT is a synthesis of behaviour therapy and cognitive therapy which uses behaviour modification techniques and cognitive restructuring. It is a short-term therapy involving five to 10 sessions, usually of one hour duration. It is a collaborative enterprise and usually involves the patient doing homework.

Unlike many other psychotherapy treatments, it is a here and now therapy as what started a problem in the past is not often what keeps it going at the present time. The behaviour modification techniques involve such things as breathing exercises and in certain cases systematic desensitisation. The cognitive therapy involves identifying and challenging negative thoughts through the use of socratic questioning and the testing of hypothesis. The success of CBT is such that, in 2009, the Department of Health (England) recommended this therapy in conjunction with sedation services as a model of excellence in the management of dental fear.

The comprehensive assessment of patients allows different psychological interventions to be considered in the treatment of patients. The work of Art De Jongh has shown that were patients have a specific memory of dental trauma, EMDR may offer complete resolution of their dental phobia. EMDR stands for eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing and has been used extensively in people suffering from post traumatic stress disorder. The traumatic nature of memory formation in these individuals means that the memory of the trauma is unprocessed and the person is plagued by intrusive thoughts and flashbacks. By a process of bilateral stimulation either visual or auditory, the memory is accessed and desensitised of its affective content and negative cognitions. The memory is then accessed again and reprocessed with much less affect and a positive cognition. I have found this to be very successful in two or three visits where a phobia follows on from a specific dental trauma even when that trauma occurred many years previously.

Dental hypnosis has been revisited in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe dental anxiety. A study by Halsband et al (2015) has demonstrated that even brief dental hypnosis sessions can have an influence on the fear processing structures of the brain. Twelve dental phobic patients and 12 healthy control patients were tested by a 3T MRI whole body scanner observing brain activity changes after brief hypnosis. In the dental phobic group, dental fear was represented in the brain by increased activity in the left amygdala and bilaterally in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), insula and hippocampus (R<L).

- Mary Downie

- Tim Newton

- William James (Portrait 1890)

- Ivan Pavlov

- René Descartes

Amazingly, during hypnosis the scan revealed significantly reduced activity in these areas. In the healthy group of patients, no amygdala activity was observed. This study demonstrates objectively what hypnotherapists have been subjectively experiencing with their dentally phobic patients. In these times of great uncertainty, the wisdom of past ages is reemerging to show us a way forward without our heavy reliance on drugs.

The currency on which most psychological treatments thrive is time, unfortunately this is in short supply in busy NHS practices. In order to give dentally anxious patients the treatment that offers possible resolution of their condition, this paper proposes that psychological services must work in collaboration with dentistry.

This article has attempted to demonstrate that psychology can and does have an influence on the way we treat and manage our patients. The next article seeks to show how the treatment of chronic oral facial pain and the stress encountered in dental practice can be positively influenced by looking outward from the biomedical model. The wisdom of great scholars has been revisited as we seek to offer both our patients and the dental team a more balanced and productive way of practising.

References

Adult Dental Health Survey 2009, NHS Digital.

Chen DC, Kirshenbaum DS, Yan J, Kirshenbaum E, Aseltine RH. Characterizing changes in student empathy throughout medical school.

Med Teach. 2012;34(4):305-11. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.644600.

DeJongh A, Adair P, Meijerink-Anderson M. Clinical Management of Dental Anxiety: What works for whom? International Dental Journal (2005) 55, 73-80

De Jongh. A, Van Den Oord. H, Ten Broeke, E. Efficacy of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing in the Treatment of Specific Phobias: Four Single-Case Studies on Dental Phobia Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 58(12), 1489–1503 (2002)

GDC Publications Preparing for Practice.

Halsband, Ulrike; Wolf, Thomas Gerhard; NLM Functional changes in brain activity after hypnosis in patients with dental phobia Journal of physiology, Paris109.4-6 (Dec 2015): 131-142.

Kani E, Asimakopoulou K, Daly B, Hare B, Lewis J, Scambler S, Scott S, and Newton JT. Characteristics of patients attending for cognitive behavioural therapy at one UK specialist unit for dental phobia and outcomes of treatment. British Dental Journal Volume 219 No. 10 Nov 27 2015

Mills I, Frost J, Kay E, and Moles DR. Person-centred care in dentistry – the patients’ perspective. British Dental Journal 218, 407 – 413 (2015) Published online: 10 April 2015 | doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.248

Newton T, Asimakopoulou K, Daly B, Scambler S, and Scott S. The management of dental anxiety: time for a sense of proportion? British Dental Journal 2012; 213: 271-2 74

Sherman J and Cramer A. Measurement of Changes in Empathy During Dental School. Journal of Dental Education Vol 69 Number 3

Woolley SM, Summary of: Who is referred for sedation for dentistry and why? Published online: 28 March 2009 | doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.233

About the author

Mary graduated from Glasgow University in 1980 and from the Open University in 2001. She obtained a postgraduate diploma in counselling and psychotherapy from Stirling University in 2013. She has enjoyed a plethora of experiences in dentistry both in the UK and abroad.She especially enjoyed her post in Glasgow University teaching oral surgery. Mary is now in full-time psychotherapy practice but would like to combine psychotherapy and dentistry if the right post became available.

A 49-year-old male patient attended for an emergency appointment due to experiencing pain and swelling from a lower left tooth/teeth. He was experiencing pain with biting and pressure. Patient had been experiencing pain from the lower left quadrant for the past few days and the tooth area had now become swollen. He reported no sleep loss or pain with temperatures reported. The quality of pain reported as a dull throbbing pain.

Patient was able to identify tooth LL4 as the source of pain. Analgesics (paracetamol and ibuprofen) had been taken.

Patient had RCT on tooth LL4 while on holiday in Las Vegas, Nevada, US, in 2003. Emergency treatment had been provided by a GDP and definitive RCT completed. A temporary restoration had been placed. On return to Scotland, a composite onlay had been provided as a definitive coronal restoration since the patient reported no pain and was reassured by the Las Vegas dentist that treatment had been completed. The radiograph copy provided by the patient showed a completed root canal treatment on tooth LL4 with all visible canals obturated. Tooth LL4 had been symptom-free until now.

Previous dental history

The patient is registered with NHS Scotland. He is a regular attender, attending six-monthly examinations and hygienist appointments. He is well-motivated about his dental health.

Previous medical history

No relevant medical history noted. No medication taken. Patient was a smoker (20 per day) up until March 2011.

Social history

Married. Telephone engineer. Non-smoker and moderate alcohol intake.

Examination

Extra-oral

Examination revealed some submandibular swelling on the left mandible. No other significant findings noted.

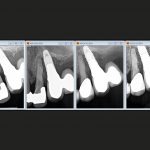

Intra-oral (Fig 1a-c)

- Soft tissues – Some gingival swelling was palpable buccal to tooth LL4. Oral mucosa, tongue, sublingual tissue and soft/hard palate appeared within normal limits. LL4 was also tender to percussion and appeared to have a small degree of mobility. No lingual swelling was noted.

- Periodontal condition – A Basic Periodontal Examination was recorded as per Table 1.

- Occlusal examination – Angles class I anterior relationship; Class I molar relationship on the left and

a Class I canine relationship on the right. Left and right lateral excursions were canine guided.

Protrusive guidance was provided by palatal surfaces of the maxillary incisors. - Dentition – The dentition present are recorded in Table 2.

The dentition was heavily restored posteriorly on the left and with 1 occlusal restoration present on the right. Upper anterior incisors had porcelain bonded crowns in situ. - Specific examination of the problem site (LL4) – Tooth LL4 was restored with a composite onlay in situ. This was fitted in 2009 and had a good marginal seal and good occlusal relationship with the maxillary teeth. Intercuspal relationship was noted and the buccal cusp was involved in left lateral excursions. There were no isolated periodontal probing defects, no signs of coronal or root fracture and the tooth was TTP.

| 2 1 4 |

| 4 3 3 |

| 7 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

|---|

| 7 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

Special investigations

Special investigations were carried out in order to form a provisional and ultimately a definitive diagnosis and to enable the formulation of a definitive treatment plan. The tests performed with results are provided in Table 3 above. The contralateral tooth was used as a control.

Special investigations

| Special test | LL3 | LR4 |

|---|---|---|

| Digital axial/horizontal pressure | Yes | No |

| TTP-axial/horizontal | Axial | No |

| Digital palpation-buccal/lingual | Buccal/lingual | No |

| Endo-Frost | No | Yes |

| EPT | No | Yes |

| Periodontal probing | Within normal limits | Within normal limits |

Radiographic examination

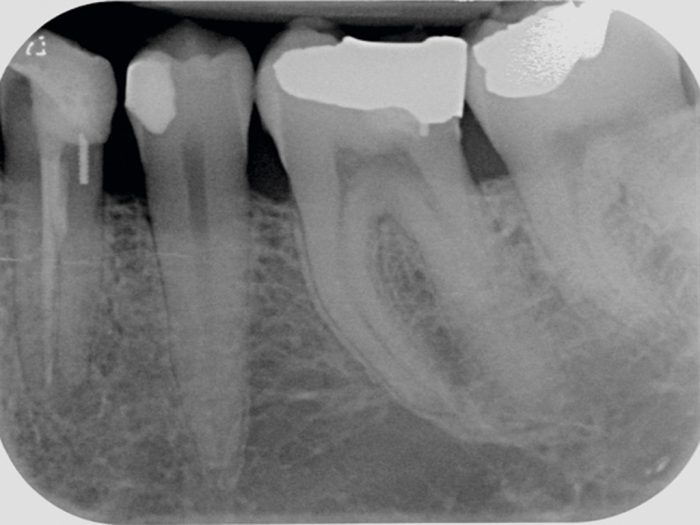

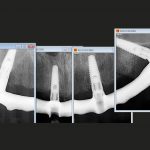

A periapical radiograph (Fig 2) taken at the emergency appointment, revealed a marginally sound coronal restoration. A dentine pin appeared to be present in the distal of the tooth. Some horizontal bone loss was evident at the distal of the tooth. A radio-opaque material was present in the root canal which appeared sub-optimal (non-homogenous obturation) and possibly short of the radiographic apex.

The root appeared wide and a ledge/step was visible mid root with the obturating material. This seemed to suggest two root canals being present with only one obturated. A feint canal root canal space is evident in the distal root. A periapical radiolucency was apparent with some widening of the periodontal ligament space.

The other teeth visible in the radiograph appeared to be clinically sound.

Provisional diagnosis

- Periodontal abscess associated with LL4

- Dental cyst associated with LL4

- Failed primary root canal treatment (apical periodontitis).

Definitive diagnosis

Moderate, non-suppurative, localised, chronic apical periodontitis with a non-obturated root canal. A failed primary root canal treatment. This diagnosis was reached after careful consideration of the clinical signs and symptoms, the special test results and the radiographic information.

Since the special test results showed digital axial/horizontal pressure with axial TTP and tenderness to buccal-lingual pressure, inflammation of the periapical tissues or apical periodontitis, was diagnosed. A dental cyst was considered and it was decided that if definitive treatment was unsuccessful then further tests would be performed to investigate possible cyst formation with associated treatment.

The patient was advised that the reason for treatment was due to bacteria being present in the un-instrumented root canal and quite possibly in the obturated canal also since the obturation appeared suboptimal. Bacterial cause of apical pathology has been shown by Kakehashi et al. 1965 and residual micro-organisms in the root canal system and cementum has been shown by Dalton et al. 1998 and Molander et al. 1999.

Strictly speaking, a definitive diagnosis is only truly possible with a histological analysis of the infected area (Nair et al. 1990 and 1999). However, the resources or facilities for this were not possible.

- Figures 1 a-c: Inra-oral clinical photographs

- Figures 1 a-c: Inra-oral clinical photographs

- Figures 1 a-c: Inra-oral clinical photographs

- Figure 2: LL4 pre-op radiograph

Treatment options

- Reduction of the infection and keep tooth LL4 under observation;

- Reduction of the infection and root canal retreatment of tooth LL4;

- Extraction of tooth LL4 with assessment for prosthetic replacement in 6 months.

Treatment plan

Since the patient was well motivated and wished for a predictable long-term solution he opted for reduction of the infection with root canal retreatment under private contract. He did not wish to keep the tooth under observation since there was a risk of his symptoms returning and he did not wish for extraction of tooth LL4, as this would have functional and aesthetic implications for him.

The treatment procedures with risks were discussed at length. The patient was advised that treatment success would be achieved by removing all of the previous obturation materials, locating the additional canal(s), chemically and mechanically disinfecting the canals and finally obturating the canals and providing a definitive coronal seal.

The patient was given the opportunity to ask questions and these were answered to the patient’s satisfaction. The patient was given a good prognosis upon successful completion of treatment with a success rate approximated at 62-86 per cent based of evidence published by Sjogren et al 1990. The patient was advised that non-surgical root canal retreatment was indicated as a primary treatment option as indicated by Rahbaran et al 2001. Consent was taken and two subsequent appointments made.

Treatment schedule

- Antibiotic prescription to reduce facial swelling

- Oral hygiene advice and instruction plus interdental cleaning demonstration

- Scale and polish

- Restorability assessment and root canal re-treatment of tooth LL4 over two visits

- Definitive composite restoration of access cavity

- Review (one year).

Items 2 and 3 were performed by the practice dental hygienist.

The second part of this article will look at the treatment and case discussion.

References

Dalton BC, Rstavik D, Phillips C, Pettiette M and Trope M, 1998. Bacterial reduction with nickel-titanium rotary instrumentation. Journal of endodontics, 24(11), pp. 763-767.

Kakehashi S, Stanley HR and Fitzgerald RJ, 1965. The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 20(3), pp. 340-349.

Molander A, Reit C and Dahln G, 1999. The antimicrobial effect of calcium hydroxide in root canals pretreated with 5% iodine potassium iodide. Dental Traumatology, 15(5), pp. 205-209.

Nair PR, Sjgren U, Figdor D and Sundqvist G, 1999. Persistent periapical radiolucencies of root-filled human teeth, failed endodontic treatments, and periapical scars. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology, 87(5), pp. 617-627.

Nair PR, Sjgren U, Krey G, Kahnberg K and Sundqvist G, 1990. Intraradicular bacteria and fungi in root-filled, asymptomatic human teeth with therapy-resistant periapical lesions: a long-term light and electron microscopic follow-up study. Journal of endodontics, 16(12), pp. 580-588.

During the natural ageing process, the production of our own collagen is reduced and the elasticity of our skin degrades. There is an increasing popularity within our population today of people seeking non-invasive alternatives to skin tightening procedures to help combat the first signs of aging.

As mentioned in our previous article (SDM Nov/Dec 2016), Forma (InMode Inc, Richmond Hill, ON, Canada, North America) is a FDA-approved bipolar, non-invasive radio frequency (RF) device that generates controlled dermal heating.

Forma is based on ACE (Acquired Control Extend) technology which is comprised of the following steps:

- Acquire – Forma has a temperature sensor built into the handpiece which reads skin surface temperature 1,000 times per second, allowing clinicians to acquire skin temperature in real time.

- Control – Software algorithm allows unprecedented safety of RF delivery. The ‘cut off temperature’ feature reduces RF energy automatically when the handpiece senses that the required skin temperature has been reached.

- Extend – Clinical evidence suggests prolonged exposure to temperature above 40º C is advantageous for optimal clinical outcomes. Only InMode’s ACE technology allows you to utilise therapeutic temperatures safely and efficiently 1

Non-invasive skin tightening represents a rapidly emerging area in cosmetics, as patients increasingly seek to avoid facelifts and other invasive procedures. Non-ablative heating of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue offers the potential for skin tightening and rhytid reduction with minimal pain, downtime, and low risk of scars or other adverse events 2.

Forma is a non-invasive treatment that can be used to target fine lines, wrinkles and loose/lax skin. This treatment will stimulate new collagen formation within the skin which in turn will improve elasticity and give skin a firmer, rejuvenated appearance.

This RF device offers several advantages over currently available technologies, which likely explains this high level of clinical efficacy. The Forma device utilises real-time temperature-monitoring mechanisms, assessed by measuring tissue impedance, temperature, and epidermal contact throughout the treatment. This allows the device to continuously monitor the targeted tissue, and adjust the delivery of the RF energy to create a uniform heating exposure. The device is also able to maintain this constant uniform heating exposure for prolonged periods over relatively large treatment areas, such as an entire unilateral cheek. This uniform, long exposure is likely more effective at inducing collagen remodelling and neocollagenesis. Additionally, since the thermal exposure can be extended and prolonged, lower temperatures that do not induce any pain can be utilised 2.

The main goal for this case study is to provide further information on alternative non-invasive procedures and to demonstrate the results that can be achieved from ACE technology.

Case study

- Fig 1: first appointment

- Fig 2: first appointment

- Fig 3: first appointment

- Fig 4: final treatment

- Fig 5: final treatment

- Fig 6: Before and after comparison

- Fig 7: Before and after comparison

- Fig 8: Comparison photo

A 58-year-old female patient with skin type II, concerned about the appearance of her lower face (jowls and nasolabial folds) and neck area.

During the initial consultation the main areas of concern for the patient were established. Information was then given to the patient on the Forma treatment – how the treatment works, advised treatment schedule and the benefits. Throughout this discussion, the patient was able to ask any questions they had on the treatment.

Contraindications of the treatment were then discussed. Contraindications include – pacemaker or internal defibrillator, permanent implant in the treatment area, cosmetic fillers in the last six months, botox within the last week, a history of skin cancer or pregnancy/nursing mothers.

After all of the relevant information was given to patient and any questions answered, the patient was then able to make an informed decision as to whether she would like to proceed with the case study. Pre–treatment photos were then taken (Figs 1-3). It is essential to take pre-treatment photographs as this will provide you with a reference point throughout the entire treatment.

Treatment

The proposed treatment schedule for our patient to be able to obtain the optimum results was eight sessions of Forma at weekly intervals. Each session would last one hour and would involve treating both sides of the lower face and neck. Throughout the entire process, the patient’s face was divided into three treatment zones – right side of face, left side of face and neck. These three areas were then further divided into treatment areas which were roughly 10x10cm in size.

Each sub-divided treatment area was concentrated on individually for 10 minutes giving a total treatment time of 60 minutes. The patient’s tolerance to the treatment was very good, so the working parameters were set to the maximum recommendations from the machine’s manufacturer:

- RF = 62 for lower face (jowls and around mouth)

Temp = 43 - RF = 50 for neck, Temp = 43.

The radio frequency was reduced when treating the neck area as the skin in this area tends to be thinner and patients tend to find this area more sensitive to treat. Once the set working temperature was achieved, each area was then treated for 10 minutes. The length of time it takes to achieve the required working temperature varies depending on various external factors such as temperature of room, surface temperature of patient’s skin, etc.

After every treatment, the machine was appropriately cleaned down using 70 per cent alcohol as recommended by the manufacturer. It is essential that the appropriate safety checks are always carried out by the operator prior to use.

Feedback was obtained from our patient throughout the treatment process. She reported that she found the treatment very relaxing and could feel and see the difference in her skin after the first few treatments.

At the end of the treatment process – post-treatment photos were taken (Figs 4 and 5) and compared to original photos taken at the initial consultation (Figs 6, 7 and 8).

My experience working with the InMode Machine

As a fully qualified dental nurse, providing treatments that offer a non-invasive alternative to skin tightening is a relatively new field for me. I am aware of the increasing popularity within our population today of people seeking a wide range of facial aesthetic procedures. The InMode machine is an excellent piece of equipment to work with; it offers the clinician operating it a great deal of reassurance and confidence when providing a treatment due to all the built in safety mechanisms.

For example – monitoring the skin’s surface temperature 1,000 times per second throughout the Forma procedure. The machine is very well ergonomically designed which allows the operator to provide treatments with ease. The only minor difficulty I have occasionally experienced when providing a Forma facial is the position of the cable that attaches the handpiece to the machine. When treating a patient’s neck area, the cable can occasionally sit against their shoulder due to the working angle. However, if this is explained to the patient at the time they are always very understanding.

Results

There was a noticeable improvement in the appearance of fine lines with the skin looking rejuvenated from the treatment. The overall results from this course of treatment were excellent with the biggest change seen on the neck area – the loose/lax skin on the neck now appears much firmer than in the pre-treatment photos.

At the end of the treatment process, our patient was extremely happy with the results she achieved. After a discussion with the patient it was agreed that we had achieved a moderate result after the eight sessions of Forma. There were no adverse reactions experienced throughout this course of treatment.

The results achieved in this case were comparable to the results from a study carried out in America in 2015 3. This study was carried out treating fifteen patients with an average age of 62. They reported: “Results: All patients (14/14) were determined to have a clinical improvement, as the pre-treatment and post-treatment photographs were correctly identified by the evaluators. It was observed that 21 per cent (3/14) of patients had significant improvement, 50 per cent (7/14) had moderate improvement, and 29 per cent (4/14) had mild improvement. No pain, side-effects, or adverse events were observed.”

Feedback from all of our patients is vitally important to us. Throughout every stage of the Forma treatment and we regularly monitor how the patient is finding the treatment and if they have noticed a change in the appearance/texture of their skin. It is also important to find out how the patient is coping with the treatment, if there is anything we could do or change to improve their experience of the Forma facial.

It is also important to manage an individual’s expectations from the initial consultation throughout the treatment to the final appointment. Due to the fact Forma is a non-invasive and non-surgical procedure, it is impossible to achieve the dramatic changes you see with any invasive procedures. Patients and treatment providers will be able to see clinical improvements in their skin, however this is achieved gradually throughout the process, hence the importance of pre and post-treatment photographs.

Unrealistic expectations can leave patients feeling disappointed and disheartened with the treatment they had. If a patient is looking for a drastic change in areas of loose/lax skin and are not opposed to invasive procedures, it may be a better option for them to seek information for a suitably qualified professional on the other treatments available to them prior to proceeding with a course of Forma.

References

- inmodemd.com

- Nelson A, Beynet D and Lask GP. Non-invasive facial aesthetics. Scottish Dental magazine, Nov/Dec 2016: 52-54.

- Nelson A, Beynet D, Lask GP. A novel non-invasive radiofrequency dermal heating device for skin tightening of the face and neck. J Cosmet Laser Ther. Vol. 17, Iss. 6, 2015.

About the author

Megan Brown is a dental nurse/face and body cosmetic therapist at the Scottish Centre for Excellence in Dentistry in Glasgow.

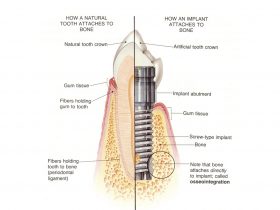

In the last issue we reviewed the literature on the validity of the use of periodontal indices to predict peri-implantitis. The conclusions were that current diagnostic tools are ineffective at predicting peri-implant problems, and, moreover, if they are used as an indicator of treatment needs, many patients will receive treatment that is of no benefit1.

To recap:

- The majority of implants will bleed on probing

- Pocket depth of >4mm cannot be used as a sign of pathology

- Increasing pocket depth alone is not an accurate predictor of peri-implant bone loss

- A single episode of bone loss is not an indicator of future bone loss and does not call for treatment, unless associated with other signs of active infection (bleeding and profuse suppuration on palpation)

- Peri-implantitis cannot occur within a year of implant placement as this is the adaptive phase of integration

- Radiographic evaluation of crestal bone levels over time seems to be the most reliable tool to identify those implants undergoing continuous bone loss and therefore in need of treatment.

The above points are uncomfortable as they may challenge what we have previously been taught in the clinical management of dental implants.

The following obvious questions arise:

- Just when should we intervene?

- Which patients really are at risk?

The bottom line, unfortunately, is that we don’t know (Figs 1 and 2). With hindsight it is, of course, easy to look at a failing implant case and postulate as to the probable causes of failure playing the, so called, “blame game”.

Likely suspects

- The patient – poor oral hygiene smoker, diabetic, previous periodontitis, bruxist, aggressive foreign body reaction

- The surgeon – surgical trauma, implant selection, positioning, technique

- The restoring dentist – occlusion, misfit, material/component choice, poor treatment planning.

While all the above factors have, at one time or another, been highlighted in crestal bone loss and failure, in reality what is more likely is, as described by Albrektsson,

a combination of a number of these factors2.

In terms of prevention of peri-implant problems, the “ideal” would be that ALL clinicians involved are experienced and knowledgeable in ALL aspects of dental implant treatment and planning, and are respectful not only of the others’ role but of their own limitations.

For example, while restoring a single tooth implant may appear simple from a technique perspective, the restorative dentist taking on this treatment has as much a role in the long-term survival of the implant as the surgeon. A poorly constructed crown can result in implant failure3.

A multidisciplinary approach can be argued to be the most effective as not only should all potential compromising factors be managed to a higher level, but responsibility is shared. It is essential, however, that such an approach is openly collaborative with the restorative dentist or prosthodontist taking the lead, as it is they that are ultimately responsible for the long-term management and care of the patient.

- Poor oral hygiene

- Crestal bone stability over seven years

- Profuse suppuration

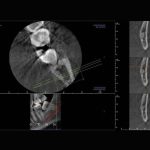

- A single radiograph cannot diagnose peri-implantitis

- Bone loss radiographic series after maturation phase 2008-9

- Progressive bone loss after maturation phase surgical debridement was carried out in 2009 bone loss continued

- Despite visible threading and poor oral hygiene this is not perimplantitis without progressive bone loss

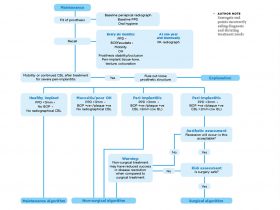

Proposed guidelines for follow-up of implants

In current practice, clinicians are challenged to provide a high level of care often within the constraints of a system which does not recognise the time/effort and expense required in providing it.

What is needed are simple diagnostic tools which can be integrated into routine daily practice, taking a minimum of time and providing a high degree of accuracy. Current implant maintenance advice does the opposite of this. Bleeding on probing and pocket charts take time and, as we now see, have a very low level of predictive accuracy.

Based on the current degree of knowledge, the most reasonable approach is that implant patients should be examined annually for the presence of clinical problems. The clinical examination should cover three areas:

Observation – absence of redness and swelling in the soft tissues, assessment of adequate plaque control4 and assessment of the occlusal scheme (paying particular attention to the possibility of parafunction and the excessive loads this may transfer to the restorations and implants)

Palpation – pressure on the tissues surrounding the implant to ensure absence of discomfort, bleeding and suppuration (see Fig 3)

Radiation – radiographs should be taken once a year during the first two to three years of function and thereafter at regular intervals (every two or three years, depending on the findings of the clinical examination and on the individual patient’s oral hygiene and co-operation) to monitor the crestal bone level stability.

It should be kept in mind that a stand alone radiograph after baseline radiography is insufficient to diagnose “disease” (Fig 4). To diagnose peri-implant health or disease, a series of radiographs from different times of follow up is needed to decide whether a particular implant has progressive loss of marginal bone (Figs 5a and 5b). Furthermore the “series” of radiographs only starts after the maturation/ adaptive phase of one year5.

Only significant, progressive loss of marginal bone, as verified in the series of radiographs, in association with clinical signs of inflammation such as redness, swelling, bleeding and suppuration at palpation and pressure on the soft tissues (not at probing) should be considered indicative of an ongoing peri-implantitis process (Fig 5c).

- FIGURE 6 – Radiographic series showing progresssive bone loss around three out of four implants

- FIGURE 7 – Clinical picture at completion of treatment

- FIGURE 8 – Surgical debridement of granulation tissue to attempt to treat suppurative infection

- FIGURE 9 – Clinical picture after healing

- FIGURE 10 – At presentation

- FIGURE 11 – Radiographic series showing stability of bone despite significant loss round implant and adjacent tooth

- FIGURE – 12 Remaining teeth and ailing implant removed and replaced for fullarch restoration

- FIGURE 13 – New baseline radiograph

- FIGURE 14 – Implant removal tool in failed implant

- FIGURE 15 – Failed implant counter rotated out to break osseointegration

Clinical aspects of true peri-implantitis lesions

True peri-implantitis lesions do of course exist, all be it in a thankfully smaller number that some might think, with an incidence of only 2.7 per cent 5. Peri-implantitis constitutes a threat to the longevity of the implant due to rapid marginal bone loss. Characteristic symptoms are, as outlined above: swelling, redness, pain and suppuration when palpating the peri-implant soft tissues in addition to the presence of rapid marginal bone loss.

The pathology of the development of a peri-implantitis lesion is not well understood. A primary peri-implantitis lesion has yet to be recognised and treatment is usually of the secondary infection which presents clinically. It is postulated that marginal bone resorption, for any reason, may have provided the conditions for a secondary infection with anaerobic bacteria, which in turn accelerates the tissue damage 2,6.

Treatment therefore should be aimed at resolving the presenting infection. This can include the use of local antibacterial rinsing, general treatment with antibiotics and surgical exploration of the area (Figs 6, 7, 8, 9).

There are, in addition, a number of innovative approaches to the surgical management of peri-implantitis lesions proposed:

- Laser treatment of cleaned implant surface

- “Implantoplasty” to attempt smoothing of the implant surface

- Use of antibiotics mixed with biomaterials to promote healing and soft tissue reattachment to the implant

- Soaking of the implant with various solutions after mechanical cleaning.

- While all these techniques show occasional impressive results to justify their use, it should be remembered, in the context of this and the previous article, that:

The diagnostic tools dictating treatment are poor and may have resulted in treatment of implants that did not actually have true peri-implantitis lesions, in which case there is little to be learned

In such cases there are no controls or long-term outcomes – these are low evidence techniques and do not justify routine practice

Surgical treatment of peri-implantitis is unpredictable whatever the method7.

As stated before, the pathology of a true peri-implantitis lesion is poorly understood. Even if the secondary infection is managed effectively, the cause of the original bone loss may still be present and continue to affect marginal bone levels. It is important, therefore, that all the potential compromising factors are also addressed (patient/surgeon/restorative).

Occasionally, bone loss results in the exposure of a large portion of the implant, deeming it unaesthetic, impossible to clean and a constant irritation for the patient. In such situations, if it has not already lost integration, removal of the implant should be considered. Implant failure is no longer a terminal event, in contrast to losing a tooth, as a new implant can be placed if a sufficient amount of bone is present. The replacement implant does not seem to be significantly worse off than any new implant might be.

Osseointegrated implants can now be removed in an atraumatic way by using a so-called removal tool. With this new development, removal of “ailing” implants can be carried out and treatment started anew, rather than lengthy, unpredictable surgical “management” (Figs 10-15).

Conclusions

There is still a lot that we do not know about peri-implantitis and hopefully future research will provide us with accurate diagnostic indicators of health and treatment needs, together with predictable management techniques. Until such a time, we need to approach peri-implant problems with a measured and pragmatic approach, assessing each case on its clinical presentation and deciding on a course of action that is best for that patient at that time.

References

1. Coli P, Christiaensen V, Sennerby L, De Bruyn H. Reliability of periodontal diagnostic tools for monitoring peri-implant health and disease. Periodontology 2000 Vol 73, 2017, 203-217.

2. Qian J, Wennerberg A, Albrektsson T. Reasons for Marginal Bone loss around Oral Implants. Clin Implant Dent Relat res 2012:14: 792-807.

3. Bryant SR. Oral implant outcomes predicted by age and site specific aspects of bone condition. PhD Thesis Department of Prosthodontics, University of Toronto, Canada 2001.

4. Attard N. Zarb G. Long term treatment outcomes in edentulous patients with implant-fixed prostheses: the Toronto study. Int. Journal Pros 2004:17:4.

5. Albrektsson T, Buser D, Sennerby L. Crestalbone loss and oral implants. ClinImplant Dent Relat Res 2012: 14: 783–791.

Albrektsson T, Dahlin C, Jemt T, Sennerby L, Turri A, Wennerberg A. Is marginal bone loss around oral implants the result of a provoked foreign body reaction? ClinImplant Dent Relat Res 2014: 16: 155–165.

Listl S. Tu Y. Assessment of endpoints in studies on peri-implantitis treatment – A systematic review. Journal of Dentistry 2010: 38: 443-450.

About the authors

Dr Kevin Lochhead is a specialist in prosthodontics and principal dentist at Edinburgh Dental Specialists. He qualified from Kings College London in 1987.

Dr Pierluigi Coli is a specialist in periodontics and prosthodontics at Edinburgh Dental Specialists. He graduated with honours in dentistry at the University of Genova, Italy in 1990. He was trained in periodontology, dental implantology and prosthodontics in the prestigious Departments of Periodontology, of Oral Rehabilitation/Branemark Clinic and of Prosthetic Dentistry/Oral Material Sciences, Faculty of Odontology, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, where he specialised

and worked during the years 1993-2007.

Professor Lars Sennerby is a visiting professor in implantology at Edinburgh Dental Specialists. He graduated from the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Gothenburg, Sweden in 1986. He joined the research group led by Prof P-I Branemark in 1982 and participated in studies on osseointegrated dental implants. In 1991 he was awarded a PhD for his thesis entitled “On the bone tissue response to titanium implants”. He was trained in oral surgery at the Branemark Clinic, Public Health Service and Faculty of Dentistry in Gothenburg and worked there part-time from 1989 to 2001.

Impacted lower third molars are a common developmental anomaly in primary care that requires an evidence-based approach to gain informed consent from patients in treatment planning. The prophylactic removal of third molars has been discouraged since the development of SIGN 43 and NICE guidelines.

The SIGN guidance suggests “surgical procedures for extraction of unerupted third molar teeth are associated with significant morbidity including pain and swelling, together with the possibility of temporary or permanent nerve damage, resulting in altered sensation of lip or tongue” 1.

The introduction of SIGN guidance initially showed a reduction in the number of cases of third molar removal in primary care. However, since 2005 there has been a steady upward trend 2. McCardle and Renton suggest this initial change resulted in patients retaining third molar teeth due to rigid interpretation of the guidance. The extraction of third molars may have been delayed due to the use of antibiotics to manage pericoronitis or a more palliative approach to clinical decision-making. As patients retain third molars into later life they are more vulnerable to caries and pathology, particularly where the teeth are impacted leading to the ‘rebound’ in data.

Inferior alveolar nerve injury is a significant complication associated with the removal of third molars and is reported to occur in up to 3.6 per cent of cases permanently and 8 per cent of cases permanently 3. Such injuries can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life and should be taken into consideration when making clinical decisions and gaining informed consent. The coronectomy technique is an alternative procedure to complete removal of a third molar in high-risk cases and can reduce the risks of nerve damage.

- FIGURE 1 – Example of low-risk case where tooth 48 is mesially impacted but not closely associated with the inferior dental canal. Note the presence of distal caries on tooth 47

- FIGURE 2 – Example of a moderate-risk case of horizontal impactions of 38 and 48

- FIGURE 3 – Example of a high-risk case where both 38 and 48 are closely associated with the inferior dental canal

- FIGURE 4 – CBCT imaging demonstrating a close relationship between the IAN and a mesially impacted 38

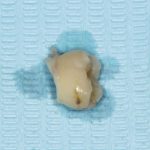

- FIGURE 5 – Roots remaining in situ after removal of crown

- FIGURE 6 – Crown sectioned below the ACJ and removed

- FIGURE 7 – Left OPT demonstrating post-op view of retained roots in situ

Assessment of lower third molars

A methodical approach to the gathering of relevant information from the clinical history is key to successful management. The guidance provided by SDCEP document ‘Oral Health Assessment and Review’ provides a comprehensive overview to history taking 4.

The patient’s history should be combined with a thorough clinical and radiographic examination. Practitioners are advised to follow IRMER 2000 5 in ensuring any exposure is justified, optimised and dose limited. Colleagues are also referred to FGDP’s ‘Selection Criteria for Dental Radiography’ 6 for guidance in their decision making process.

The guidance indicates that radiographs are indicated in the “extraction of teeth or roots that are impacted, buried or likely to have a close relationship to important anatomical structures. With the exception of third molars, the appropriate radiograph will normally be a periapical view”. As a result, an OPT is generally the radiograph of choice for assessment.

All images should be reported on by the practitioner and particular attention paid to the following radiographic signs that could result in a higher risk of inferior alveolar nerve damage as described by Palma-Carrió et al 7:

- Darkening of the root

- Deflection of the root

- Narrowing of the root

- Bifid root apex

- Diversion of the canal

- Narrowing of the canal

- Interruption in white line of canal.

Colleagues are advised to make an assessment of the difficulty of the case and their own surgical skills before considering the options of surgery in primary care, referral to a dentist with a special interest in oral surgery or referral to secondary care. Some radiographic examples are shown in Figs 1-3.

CBCT

In high-risk cases, the European Commission Cone Beam CT for Dental and Maxillofacial Radiology 8 guidance states: “Where conventional radiographs suggest a direct inter-relationship between a mandibular third molar and the mandibular canal, and where a decision to perform surgical removal has been made, CBCT may be indicated.”

Matzen et al carried out a study of 186 lower third molars that were assessed using both panoramic imaging and CBCT to decide whether surgical removal or coronectomy was indicated 9. Treatment planning was carried out after the initial two-dimensional imaging followed by a second treatment plan after three-dimensional imaging. The authors found that the treatment plan was changed for 22 teeth and thus CBCT influenced the decision making process in 12 per cent of cases. The authors advised that “narrowing of the canal lumen and canals positioned in a bending groove or in the root complex observed in CBCT images were a significant factor for deciding on coronectomy”.

The example in Figure 4 demonstrates a case of a mesially impacted tooth 38 that required CBCT investigation as part of the examination and consent process. CBCT demonstrated a close relationship between the roots of 38 and the IDN. In this case, the patient was offered the opportunity of both surgical removal and coronectomy. Given the potential for altered sensation or numbness, the patient opted to undergo a coronectomy.

Given the significant impact of CBCT imaging in treatment planning it is essential that patients in high-risk cases are offered three dimensional imaging and coronectomy where appropriate in order to gain informed consent.

Evaluation of findings and consent

On reviewing the findings of both clinical and radiographic assessment, clinicians should refer to the guidance available in the UK in deciding whether surgery is indicated 1,10,11:

- One or more episodes of pericoronitis

- Caries in the third molar or lower second molar. The future risk of caries in the second molar should be taken into account

- Pulpal/periapical pathology

- Periodontal disease

- Internal/external resorption of the tooth or adjacent teeth

- Follicle disease including dentigerous cysts

- Prophylactic removal in specific medical conditions such as before chemotherapy/radiotherapy

- To facilitate effective restorative treatment including prosthesis

- Patients whose lifestyle precludes ready access to

dental care.

This list is not exhaustive and practitioners are advised to make an individualised risk assessment and assist patients in making informed decisions in relation to their ongoing care.

Consent

Informed consent is an essential part of the assessment process and it is advisable to obtain written consent.

Patients should be alerted to the following risks:

- Pain and discomfort

- Swelling and trismus

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Localised alveolar osteitis or infection (around 20 per cent of cases)2

- OAF/OAC in the case of upper third molars

- Paraesthesia or anaesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve or lingual nerve in lower third molars (8 per cent temporarily and up to 3.6 per cent of cases permanently) 3.

In high-risk cases, patients should be offered the opportunity of a coronectomy procedure where appropriate. Patients should be aware of the possible need for a second surgical procedure at a later date and the possibility that, should the roots become mobile, the need for complete extraction 12.

Patients should be given adequate time to consider the risks involved and an opportunity to have their queries answered, this may involve a second visit to allow sufficient time.

Procedure

The coronectomy technique or “deliberate vital root retention” is a means of removing the crown of the tooth but leaving roots intimately related to the inferior alveolar nerve untouched in order to reduce the risk of nerve damage. The procedure is carried out as follows 13:

IDB and long buccal infiltration anaesthesia are provided. The author’s preference is lidocaine 2 per cent, 1:80000 adrenaline, as an IDB and articaine 4 per cent, 1:100000 adrenaline, given as a buccal infiltration.

A full thickness mucoperiosteal flap is raised to obtain sufficient access and expose the third molar tooth.

A fissure bur is used to remove buccal bone and expose the crown of the tooth down to the ACJ. The fissure bur is used to drill into the pulp at the mid centre of the buccal grove as it intersects with the ACJ. This cut is lateralised to create space for an elevator. The cut should be no more than the length of the bur in order to avoid perforation of the lingual cortical plate.

An elevator, such as a Coupland’s or straight Warwick James, is used to fracture the crown from the roots. It is essential to take care and not apply too much pressure at this stage to prevent mobilisation of the roots. If mobilisation occurs, the roots must be elevated and removed.

A rosehead bur can then be used to remove any spurs of enamel and to reduce the roots a few millimeters below the alveolar bone crest.

The pulp chamber is left untouched and primary closure with resorbable sutures.

Contraindications

- Contraindications to coronectomy include:

- Teeth with active infection

- Mobile teeth

- Deep horizontal impactions as sectioning of the crown could in itself endanger the nerve 14.

Complications

Complications after coronectomy are rare but include

the following:

- Pain

- Infection

- Alveolar osteitis

Failed coronectomy i.e. mobilisation of the roots (9-38 per cent) - Inferior alveolar nerve injury

- Root migration (30 per cent) 14.

Post-operative pain is an expected complication but the more conservative nature of the coronectomy procedure results in less tissue disturbance and thus less post-operative pain than conventional surgical removal. Simple analgesia such as paracetamol and NSAIDs is adequate for post-operative pain relief in most patients 15.

The incidence of alveolar osteitis is 10 to 12 per cent. Should ‘dry socket’ occur, the management is similar to that in extractions of irrigation and placement of a dressing. Rates of infection after coronectomy range from 0.98 to 5.2 per cent. Local measures with antibiotics as an adjunct can be used to manage. If the retained root fragment is involved it may need to be retrieved, however, this is rare 15.

O’Riordan demonstrated in a study of 100 patients that the risk of infection was minimal and morbidity less after coronectomy than after surgical removal. Over the subsequent two years some roots migrated coronally and were removed under LA 16. Given the reduced risks of nerve injury, it has been recommended for patients where there is a high risk of nerve injury.

Root migration is estimated to occur in between 14 per cent and 81 per cent of cases. Pogrel estimates root migration of approximately 30 per cent over a six-month period 18. Similar results were found by Knutsson et al on a prospective trial of 33 patients where, after one year, all but six roots had migrated between 1 and 4mm 19. Migration can continue to the point where eruption into the oral cavity occurs. If this occurs, the roots will require retrieval but this is often at less risk than originally due to their migration away from the inferior alveolar nerve 15.

Conclusion

Inferior alveolar nerve injuries during third molar surgery can be reduced by:

- Thorough clinical assessment and decision making in line with guidance

- The use of appropriate imaging, including CBCT, to identify high-risk cases

- The use of the coronectomy technique where appropriate to prevent trauma to the inferior alveolar nerve.

Clinicians should consider coronectomy as an alternative to surgical removal for patients who are at a high risk of iatrogenic nerve injury.

References

- Management of unerupted and impacted third molar teeth. 1st ed. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; 2000.

- McArdle L, Renton T. The effects of NICE guidelines on the management of third molar teeth. Br Dent J. 2012;213(5):E8-E8.

- Howe GL, Poyton HG. Prevention of damage to the inferior dental nerve during the extraction of mandibular third molars. Br Dent J 1960; 109: 355–363.

- SDCEP Oral Health Assessment and Review Guidance – Published March 2011. Available from: www.sdcep.org.uk/published-guidance/oral-health-assessment

- Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposures) Regulations 2000 (IRMER). Available from: www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2000/1059/contents/made

- FGDP – Selection Criteria for Dental Radiography: Third Edition. Published 2015. Accessed 14/06/2015. Available from www.fgdp.org.uk/publications/selection-criteria-for-dental-radiography1.ashx

- Palma-Carrio C, Garcia-Mira B, Larrazabal-Moron C, Penarrocha-Diago M. Radiographic signs associated with inferior alveolar nerve damage following lower third molar extraction. Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 2010;:e886-e890.

- European Commission – Radiation Protection No. 172 Cone Beam CT for Dental and Maxillofacial Radiology (Evidence-based Guidelines). Published 2012. Available from: www.sedentexct.eu/files/radiation_protection_172.pdf

- Matzen L, Christensen J, Hintze H, Schou S, Wenzel A. Influence of cone beam CT on treatment plan before surgical intervention of mandibular third molars and impact of radiographic factors on deciding on coronectomy vs. surgical removal. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology. 2013;42(1):98870341-98870341.

- SIGN 43 – Management of Unerupted and Impacted Third Molar Teeth. Sign.ac.uk. Guidelines by topic. Available from: http://sign.ac.uk/guidelines/published/index.html#Dentistry

- NICE – Guidance on the Extraction of Wisdom Teeth. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta1

- Renton. T, Notes on Coronectomy. Br Dent J 2012; 212: 323-326

- Renton. T, Update on Coronectomy. A Safer Way to Remove High Risk Mandibular Third Molars Dent Update 2013; 40: 362–368

- Ahmed. C et al – Coronectomy of Third Molar: A Reduced Risk Technique for Inferior Alveolar Nerve Damage. Dent Update 2011; 38: 267–276

- Patel V, Gleeson C, Kwok J, Sproat C. Coronectomy practice. Paper 2: complications and long term management. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2013;51(4):347-352.

- O’Riordan B. Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997; 35: 209–212.

- Zola MB. Avoiding anaesthesia by root retention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992; 50: 419–421.

- Pogrel MA. Coronectomy to prevent damage to the inferior alveolar nerve. Alpha Omegan 2009; 102: 61–67.

- Knutsson K, Lysell L, Rohlin M. Postoperative status after partial removal of the mandibular third molar. Swed Dent J 1989; 13: 15–22.

About the authors

Michael Dhesi is a GDP at Clyde Dental Centre. He qualified in 2012 with BDS(Hons) from the University of Glasgow and has subsequently completed MFDS RCPS(Glasg) and an MSc in Advanced General Dental Practice at the University of Birmingham. Michael’s focus is in minimally invasive and adhesive restorative dentistry.

He also has interests in the management of dental anxiety and oral surgery and welcomes referrals in these areas.

Clive Schmulian qualified from Glasgow University in 1993. Throughout his time in general dental practice, he has developed his clinical skills by obtaining a range of postgraduate qualifications, which in turn led him to develop an interest in digital imaging in both surgical and restorative dentistry. He is a director of Clyde Munro.

In 2013, 14 per cent of the world’s population was over 60 years of age. It is estimated that, by 2050, this figure will have increased to 19 per cent 1. However, as people age they develop more health conditions. Multimorbidity is the “presence of two or more diseases in one person” 2. Research indicates that, by 70 years of age, 63 per cent of people can expect to have developed two or more disorders 3.

Common chronic conditions in the elderly include cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, depression, COPD and osteoarthritis. Multimorbidity has been shown to impact immune function greater than age alone 4.

These multiple chronic conditions can also result in polypharmacy where patients have to manage an increasing number of medications. In Europe, over half of the elderly population take more than six medications per day 5. This results in an increased risk of adverse drug events. Treatment plans for an elderly patient should be based on their individual risk factors, functional difficulties and preferences.

A growing elderly population increases the indications for partial removable dental prostheses and expands the indications for implant therapy. When considering implant surgery in elderly patients, pre-operative medical fitness is more important than chronological age 6.

The standard of care in geriatric patients has to be adapted to the patient’s motivation, medical condition and socio-economic circumstances. Oral health can significantly affect an elderly patient’s nutritional intake. It has been found that complete denture wearers have thinner masseter muscles whereas implant retained over-dentures lead to increased muscle thickness 7. Unlike most adults, a BMI >25 in elderly patients is associated with a reduced mortality. It is therefore important that elderly people can chew adequately to avoid restricted diets which offer lower nutritional values 8.

Medical consideration in elderly patients considering dental implant treatment

Cardiovascular diseases

These can be divided into atherosclerosis, hypertension, chronic heart failure and atrial fibrillation. A recent myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular surgery is an absolute contraindication to implant surgery 9. Medical control of the disease is imperative prior to implant therapy. Patients with stent implantation after coronary artery disease usually have dual antiplatelet blood-thinning therapy to prevent clot formation.

Bleeding disorders

Bleeding can be prolonged in patients with haemophilia or those taking medication such as warfarin for anticoagulation. Current recommendations advise against modifying the anticoagulation provided the INR is <3.5. The exception may occur upon consultation with the patient’s medical team in cases of high volume bone grafting or extensive flaps. Splints can be used to manage expected bleeding.

The number of patients taking new oral anticoagulants such as dabigatran and rivaroxiban is increasing. New oral anticoagulants do not require monitoring, however, they lack a reversal agent. It is important that dentists follow the most recent guidelines regarding the management of these patients especially when considering invasive implant surgery 10.

Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus

This can result in delayed wound healing, an impaired response to infection and susceptibility to periodontal disease. Dentists should check their patient’s HbA1C (glycosylated haemoglobin) prior to implant placement. Implant and bone augmentation surgery in an uncontrolled diabetic can lead to serious wound healing complications.

- FIGURE 1 – Removable partial chrome cobalt denture

- FIGURE 2 – Extended implant fixed partial denture

- FIGURE 3 – Lower implant over-denture bar

- FIGURE 4 – Implant-retained over-denture

Osteoporosis

A decrease in bone mass and bone density increases the risk of fracture. Oral bisphosphonates reduce osteoclast function increasing the risk of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral bisphosphonates are a potential risk factor for osteonecrosis of the jaw but not for implant success and survival 11.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Chronic bronchitis and emphysema result in a chronic cough, sputum production and shortness of breath. Special consideration needs to be given to the type of local anaesthetic administered. It is recommended that the maximum dose of local anaesthetic be halved in patients >65 due to reduced liver function 12. Also dentists should be mindful of the risk of adrenal insufficiency in elderly patients taking long-term steroids.

Psychological conditions

Depression is common among the elderly population. At the age of 90, three out of four patients have a diagnosis of dementia 13.

Treatment planning options

Shortened dental arch concept

The shortened dental arch is where 10 upper teeth oppose 10 lower teeth 14. Dentists can reduce the biological risks for the patient and avoid problems of low acceptance by providing this treatment option 15. Gerritsen et al concluded that a shortened dental arch can last for 30 years and that there is no recommendation for adding a partial denture. McKenna et al also examined the shortened dental arch concept in 89 patients who were >65 years old. His results demonstrated a better oral health related quality of life score in patients with a shortened dental arch compared with those wearing removable partial dentures 16.

Removable partial dentures (RPD)

This is an economical prosthodontic solution involving sound abutment teeth for increased retention. It helps maintain teeth of strategic value if implants are not an option 17. The prosthetic flange can also maintain facial fullness. However, abutment teeth for removable partial dentures are high risk for both caries and periodontal disease.

Prognostic factors for partial RPD abutments include 18:

- Crown-root ratio

- Root canal treatment

- Periodontal pocket depth

- Type of abutment – multi-rooted maxillary molars can make for unfavourable abutments

- Occlusal support and function of the abutment tooth.

Partial removable dentures with implants

Conventional dentures have limitations as oral function can decline with age. Old age is not a contraindication for dental implant treatment however; some medical conditions can increase their risk of failure. It is the degree of systemic disease control that is important rather than the nature of the disorder itself. Dentists should consider the American Society of Anesthesiology’s (ASA) Classification. The ASA restricts dental implants to ASA 1 and 2 patients. Dental implant placement may be undertaken in some very carefully considered ASA 3 cases.

In comparison with conventional dentures, implant over-dentures have the advantage of slowing peri-implant bone resorption and preventing bone atrophy 19. There is also a significant improvement in chewing ability with two lower implant supported over-dentures as a result of improved muscle co-ordination. Implants increase support, retention and can improve the aesthetic outcome of dentures by avoiding the use of clasps which results in greater patient satisfaction.

Strategic implant positioning can also help convert a Class I and Class II Kennedy arch into a Kennedy Class III configuration following the extraction of a hopeless abutment. This improves the elderly patient’s ability to eat harder food when compared with a conventional complete denture. This encourages elderly patients to eat a more diverse diet, which not only boosts their nutritional intake, but also enables them when socialising to finish their meals at the same time as family and friends 20.

Implant-supported over-dentures are also associated with psychological benefits such as improved social interactions and better self-confidence. Wismeijer et al examined patient satisfaction among 36 conventional and implant assisted partial denture wearers 21. The results showed a significant improvement in patient satisfaction with support of healing caps on implants as opposed to the conventional partial removable denture by itself. There was an even greater improvement in patient satisfaction when ball anchors were attached to the implants for retention.

In cases where patients are fully edentulous the recommended configurations are:

- Four or more implants in maxilla

- Two or more implants in mandible.

Removable options for the fully edentulous patient

The McGill Consensus statement on over-dentures recommends that “a two-implant over-denture should become the first choice of treatment for the edentulous mandible” 22. Implant-retained over-denture designs should be easy to clean, repair and also to re-activate retention. Long-term results suggest that a mandibular over-denture retained by two implants with a single bar may be the best treatment strategy for edentulous patients with an

atrophic ridge.

A bar can remove pressure from the tissue 23. There appears to be no influence with regards to the length of the cantilever arm (up to 12mm) and crestal bone loss 24. There is also good evidence to support the use of four implants with single retentive elements in the maxilla with a conventional loading protocol 25.

Combination syndrome

Two implants have an axis of rotation meaning that forces on the posterior ridge are higher than if the patient had a complete denture. Anterior flabby ridges and more posterior ridge loss can result from two implants necessitating more frequent denture relining in the upper jaw 26.

Short and reduced diameter implants

Short and reduced diameter implants are increasingly making dental implants possible in low and narrow alveolar ridges. They preserve bone and reduce the mouth opening requirements for an elderly patient. The surgery is less invasive and the need for augmentation procedures is eliminated, which results in less surgical morbidity.

The reduced complexity of the procedure also reduces the financial burden on the patient. Short and narrow implants make the reversible ‘backing off’ strategy easier if for instance a patient undergoing chemotherapy can no longer manage their dentures.

Implant configurations for Fixed Dental Prosthesis (FDP)

It is not necessary to replace every tooth that is missing in an elderly patient. Careful assessment is required when choosing the type and dimensions of implants. The minimal distance between teeth and implants must be respected and also bearing in mind the need for pink aesthetics. Short edentulous spaces that comprise of three missing teeth can normally be restored with two implants. Cantilevers help avoid bone augmentation procedures which can reduce the surgical morbidity for elderly patients.