As a dentist working in general practice it is imperative to ensure that valid consent has been obtained for each individual patient. Following on from the judgement in the Montgomery case in March 2015, which brought the law of consent up to speed with what the GDC’s ethical and professional guidance expected registrants to do, this article looks at the responsibilities of the general dental practitioner. The importance of excellent communication is highlighted in order to provide sufficient and relevant information to the particular patient you have sitting in your dental chair.

The GDC has set out nine principles in their Standards for the Dental Team document. One of the key principles is obtaining valid consent. This document sets out the standards of conduct, performance and ethics that govern you as a dental professional. The guidance applies to all members of the dental team.

Why do we obtain consent?

For a GDP, there are ethical and moral obligations to ensure that your patient understands the treatment proposed and for consent to be valid. Consent is important because any investigation or treatment carried out without a patient’s consent or proper authority may be regarded as assault. This can lead to further investigations resulting in criminal proceedings, an action for damages, a breach in the duty of care and a finding of impaired fitness to practise by the GDC. There are cases where this is exactly what has happened.

Adults with capacity

The test for capacity and the ability of a patient to undertake decisions is set out in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) and are supported by the code of practice established under the act, which dental professionals are expected to follow.

In the case of a patient undergoing a dental examination, consent is the expressed or implied permission of a patient to undergo this check-up, investigation and treatment. It is essential that consent is given freely and with adequate understanding of the condition to be treated, the procedures involved, other treatment options and the health implications of giving and withholding consent. It is also important to check that the patient understands the information given.

Adults without capacity

When making decisions on behalf of adults lacking capacity there are a number of points to consider. In Scotland, under the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000, a competent adult can nominate a welfare attorney to make decisions on their behalf should they lose capacity to make those decisions themselves. The law also provides general power to treat a patient who is unable to give consent.

The dental professional responsible for treatment must have completed a certificate of incapacity before any treatment is undertaken, other than in an emergency. Put simply, decide what constitutes a patient’s best interests by taking into account factors other than just their dental condition – treat the patient holistically. Consider consulting with others, including getting a second opinion from a colleague before starting treatment.

Consent and children under the age of 16

Children under the age of 16 can give valid consent to treatment if they are deemed to be Gillick competent. The ability for a child to give valid consent depends on their maturity and understanding. To be Gillick competent, a child must understand the proposed treatment, risks and alternatives, they must be able to retain that information and be able to weigh up the pros and cons of the treatment. The child must be able to communicate that their decision to have the treatment.

If a child is not deemed to be Gillick competent then someone with parental responsibility must provide this authority. It is important to note that emergency care should not be delayed in order to prevent serious harm. In deciding whether or not to treat, the child’s best interests must be considered. Even if a child is Gillick competent, I always encourage an open dialogue between parents and children when it comes to making decisions regarding their health.

Criteria for consent

It is fundamental that valid consent is obtained before starting any treatment. You must make sure that your patient understands the decisions they are being asked to make and that the consent is valid at each stage of the treatment or investigation. Having good communication with your patients is vital in order to obtain valid consent. The way consent is obtained must be tailored to suit the patient’s needs.

As the Standards for the Dental Team states, patients must be given: options for treatment, risks, benefits, why a treatment is necessary and appropriate, consequences and risks of the proposed treatment, prognosis and consequences of not having the treatment, whether the treatment is guaranteed and for how long. Failure to give correct or sufficient information may result in a breach in your duty of care and if proven there was a negligent failure to inform and, as a direct result the patient suffered harm, the patient may take further action.

The cost of any examination, investigation or treatment should also be explained before it starts. It is important to note that a patient who pays the bill has not necessarily consented to treatment. If a patient’s condition changes, causing a change in the proposed risks, then consent must be obtained again, any changes in cost must also be reviewed with the patient. Duress of any form, such as influence from someone else can invalidate consent.

The advice from the Dental Defence Union is to ideally have a ‘cooling off’ period in which the patient can think over their decision and can seek further advice on this if they need to do so. It is best to re-confirm consent with a patient immediately before any treatment. You should also include as much information in your notes about those discussions as possible.

Consent checklist

By developing a logical approach in your daily practice you can ensure that the consent obtained is valid. The patient should be aware of the purpose, nature, and likely effects, risks, chances of success of a proposed procedure, and of any alternatives to it. It is important to note that consent is not open ended and must be obtained again at subsequent occasions. Consent must be obtained for specific procedures, on specific occasions. When the patient is in your dental chair you need to be certain that valid, informed consent has been obtained.

The following checklist is reproduced from the Consent – Scotland publication from Dental Protection Limited (http://bit.ly/DPLconsent)

Ask yourself:

- Is my patient capable of making a decision? Is the decision made voluntary and without coercion in terms of the balance/bias of the information given, or the timing or context of its provision?

- Does my patient need this treatment? Remember, if it is an elective procedure then the onus upon a clinician to communicate information and warnings become much greater. The procedural steps, risks and recovery should be discussed in detail prior to the treatment appointment and the patient should be given adequate time to consider the information given.

- What will happen in the circumstances of this particular case – what will happen if I proceed with the treatment? Is my patient fully aware of my assessment in clear terms? Can I predict the outcome accurately? If not, then what are the areas of doubt and what are the possible alternative outcomes?

- What should a reasonable person expect to be told about proposed treatment? In this case, is there anything specifically important or relevant about my patient? (If in doubt then you are not ready to proceed with the proposed treatment).

- Does information for my patient need to be provided in writing or has my patient requested a wish to have written information? Remember, if you are relying on providing information through marketing material, it is important to make sure that it is presented in a balanced and unbiased manner.

- Accurate and contemporaneous records are imperative. Do my records accurately reflect the conversations with my patient? Will these notes allow me to show what information was given to my patient? On what terms and what was said at what time?

- Does my patient understand what treatment they have agreed to and why? Have they been given the opportunity and adequate time to consider the treatment and its implications, and time to raise concerns and/or have their questions answered?

- Does my patient understand the costs involved? As well as the potential future costs in terms of complications?

- Does my patient need time to consider the treatment options proposed or is my patient wishing to discuss proposals with someone else?

- If I am inexperienced at carrying out the procedure in question, does my patient know that? Is my patient aware that their prospects of a successful outcome if they choose to have the procedure carried out by a specialist or a more experience colleague? Is the technique being used relatively new/untried and does my patient understand this?

References

1. General Dental Council. Standards for the Dental Team. Guidance of obtaining valid consent. GDC; 30 September 2013. Available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/api/files/NEW%20Standards%20for%20the%20Dental%20Team.pdf [Accessed on 21/10/17]

2. Dental Protection. Consent – Scotland. Dental Protection Limited. Available at http://bit.ly/DPLconsent [Accessed on 22/10/17]

3. ISD Scotland. Dental Statistics – NHS Registration and participation. A National Statistics Publication for Scotland; 2017. Available at: www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Dental-Care/Publications/2017-01-24/2017-01-24-Dental-Report.pdf?49161928893 Accessed 30/10/2017

4. Dental Defense Union Guide – Consent guide [Accessed 25/10/17]

5. Harris J, Sidebotham P, Welbury R. Child protection and the dental team. An introduction to safeguarding children in dental practice. Sheffield: Committee of Postgraduate Dental Deans and Directors, 2006. Available at: bda.org/childprotection [Accessed 15/10/2017]

6. Department of Health. National Institute for Clinical Excellence – Consent, procedures for which the benefits and risks are uncertain. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg56/documents/consent-procedures-for-which-the-benefits-and-risks-are-uncertain2 [Accessed 30/10/2017]

About the author

Aisha Shafi is a general dental practitioner with a special interest in cosmetic dentistry and facial aesthetics, currently working in clinics based in Glasgow, London and Portsmouth. She was a finalist for Dentist of the Year at the Scottish Dental Awards 2017 and shortlisted for ‘Best Professional’ with the Scottish Asian Business Awards.

Aisha helps run the British Smile Foundation, a group that actively promotes oral health education in the community and is now pending charity registration with the OSCR.

The use of silver-based compounds as antimicrobial agents has been well-documented and common practice for more than 100 years in both medicine and dentistry. From wound dressings to water purification systems, Ag+ is able to destroy pathogens at concentrations of <50ppm. More recently, the use of silver diamine fluoride (SDF) in dentistry has been increasing with applications including caries prevention, arresting carious lesions and the treatment of sensitivity 1.

There are a vast number of products that have been used to deliver fluoride in the aim of preventing caries including milk, salt, toothpaste and varnish. It is thought that where SDF differs is that the silver salt component has a potent antibacterial effect with the ability to encourage the formation of calcified/sclerotic dentine while the fluoride provides a remineralising effect. As such, SDF has stimulated significant interest in the prevention and treatment of caries worldwide based on its ability to reduce instances of pain, ease of use, affordability, non-invasive nature and minimal clinical time for application 1.

SDF is a colourless topical agent with a large number of practical clinical applications in dentistry including 2:

1) Prevention and treatment of high caries risk patients including both children and adults.

2) Prevention and treatment of caries in patients who are medically compromised.

3) Treatment of root surface caries.

4) Treatment of dentine hypersensitivity.

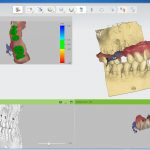

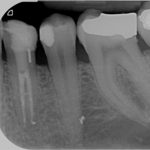

SDF is commercially available in the UK as Riva Star by SDI. The formulation is based on two coloured capsules, silver and green, that must both be applied. Application of SDF is a relatively simple process. The teeth must be cleaned with prophy paste to remove plaque debris before being dried and isolated with cotton wool rolls. If applying close to the gingival margin the kit contains a gingival barrier or alternatively some Vaseline can be placed. The silver capsule is applied first followed by green that causes the formation of a white precipitate. Each capsule can be used to treat around five teeth (see Figs 1-3).

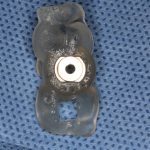

Where being used in the treatment of caries it is important that patients are aware that the aim is to arrest the lesion that will result in a dark appearance (Fig 3). Temporary staining of the gingivae is also possible. Repeated application, twice annually, is essential where the aim is to arrest a carious lesion or to treat dentine hypersensitivity.

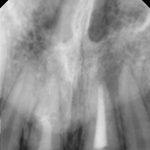

- Figure 1. Root surface caries

- Figure 2. Application of Riva Star silver fluoride

- Figure 3. Application of Riva Star potassium iodide

- Figure 4. Post-treatment root surface

- Figure 5. Post-treatment deciduous molar tooth

Caries prevention

A systematic review by Rosenblatt et al. conducted a review of the literature on the use of SDF between 1966 and 2006, identifying 99 papers. The authors were able to conclude that SDF is more effective than fluoride varnish and may be a valuable preventative intervention. They also noted that SDF is a “safe, effective, efficient and equitable caries preventive agent that meets the criteria of the WHO millennium goals”1.

In 2017, a further review of the literature conducted by Contreras et al. found 33 publications meeting the inclusion criteria that were published between 2005 and 2016. The group were able to conclude that SDF is an “effective preventative treatment in a community setting” and that is “shows potential to arrest caries in the primary dentition and permanent first molars”3.

Caries treatment

Chu et al. carried out a study on the use of SDF in arresting carious lesions in 370 Chinese pre-school children aged three to five years old. They compared groups of children receiving SDF treatment, sodium fluoride varnish and a control. The children were followed up for 30 months receiving an intervention every three months.

Children in the SDF groups had a mean of 2.8 arrested lesions compared with a mean of 1.5 in the varnish group. They were able to conclude that the application of an SDF solution was more effective in arresting dentine caries in primary teeth compared with sodium fluoride vanish 4.

Similar results are echoed in a study by Lo et al. which followed 375 Chinese pre-school children over an 18-month period comparing groups of children receiving treatment with SDF, NaF varnish and a control. They found a mean of 0.4 new carious lesions in the SDF treated group compared with 1.2 in the control. They also found similar results in arresting active carious lesions with a mean of 2.8 arrested lesions in the SDF group compared to 1.5 in the NaF varnish group 5.

Clemens et al. treated 118 active lesions with SDF in a community dental clinic in Oregon. They were able to follow up 102 lesions on a three-monthly recall basis and found that 100 lesions were arrested by the first recall and all lesions by the second recall. The authors also noted no incidence of pain or infection and that the parents had a favourable view of the treatment modality 6.

Adults patients have also found a beneficial effect from SDF treatment. Zhang et al. followed up 227 elderly patients over 24 months who were provided with SDF and oral health education compared with a control group. They found a statistically significant result in that the SDF group had fewer root surface lesions than the control group. The authors concluded that SDF combined with oral health education was effective in preventing new root caries and arresting existing lesions in elderly patients 7.

Treatment of sensitivity

Castillo et al carried out a randomised control trial in 126 adult patients experiencing dentine hypersensitivity to assess the effectiveness of SDF as a desensitising agent. They found a reduction in sensitivity at seven days that was statistically significant (p<0.001) compared with the control group and were able to conclude that SDF is a clinically effective desensitising treatment 8.

Guidelines

In October 2017, the American Academy of Paediatric Dentistry issued the first ever evidence-based guideline for the use of SDF in the treatment of dental caries. This followed a systematic review of research between 1969 and 2016. The guideline hopes to lead to a more widespread adoption of SDF as a treatment for dental caries in paediatric and special needs patients 9.

The AAPD describe SDF as the “single greatest innovation in paediatric dental health in the last century aside from water fluoridation” noting the cost effective and pain-free benefits of treatment.

The systematic review on which the guideline is based notes no adverse effects but that a ‘downside’ is the black appearance of cavities. The potential to reduce the number of paediatric cases requiring sedation or GA is high.

The chairside guide suggests that patients who may benefit from SDF include 10:

- High caries risk individuals with active cavitated carious lesions in anterior or posterior teeth

- Patients with additional behavioural or medical challenges who present with cavitated carious lesions

- Multiple cavitated lesions that may not all be treated in a single visit

- Patients with limited access to dental care.

- The chairside guide also suggests the following criteria for tooth selection 9:

- No clinical signs of pulpal inflammation or reports of spontaneous pain

- Cavitated lesions not encroaching on pulp

- Lesions are accessible by a brush to apply SDF (orthodontic separators may be used to help gain access to interproximal regions).

Follow-up is recommended two to four weeks after treatment. Arrested lesions can subsequently be restored. However, where lesions are not restored, biannual re-application is recommended.

In conclusion, silver diamine fluoride is safe and effective in the prevention and treatment of dental caries as well as providing a further treatment modality in the management of dentine hypersensitivity. Application twice annually is a minimally invasive, cost-effective treatment that demonstrates a potentially vast benefit to patients of all ages.

References

1. Rosenblatt A, Stamford T and Niederman R. (2009). Silver Diamine Fluoride: A Caries “Silver-Fluoride Bullet”. Journal of Dental Research, 88(2), pp.116-125.

2. JUCSF protocol for caries arrest using silver diamine fluoride: rationale, indications, and consent. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2016 Jan; 44(1): 16–28.

3. Contreras et al. 2017. Effectiveness of silver diamine fluoride in caries prevention and arrest: a systematic literature review Gen Dent. 2017 May-Jun; 65(3): 22–29..

4. Chu C, Lo E and Lin H. (2002). Effectiveness of Silver Diamine Fluoride and Sodium Fluoride Varnish in Arresting Dentin Caries in Chinese Pre-school Children. Journal of Dental Research, 81(11), pp.767-770.

5. Lo E, Chu C and Lin H. (2001). A Community-based Caries Control Program for Pre-school Children Using Topical Fluorides: 18-month Results. Journal of Dental Research, 80(12), pp.2071-2074.

6. Clemens J, Gold J and Chaffin J. (2017). Effect and acceptance of silver diamine fluoride treatment on dental caries in primary teeth. Journal of Public Health Dentistry.

7. Chu C, Lo E and Lin H. (2002). Effectiveness of Silver Diamine Fluoride and Sodium Fluoride Varnish in Arresting Dentin Caries in Chinese Pre-school Children. Journal of Dental Research, 81(11), pp.767-770.

8. Castillo J, Rivera S, Aparicio T, Lazo R, Aw T, Mancl L and Milgrom P. (2010). The Short-term Effects of Diammine Silver Fluoride on Tooth Sensitivity. Journal of Dental Research, 90(2), pp.203-208.

9. Chairside Guide: Silver Diamine Fluoride in the Management of Dental Caries Lesions. AAPD Reference Manual v 39. No.6, 17/18. Accessed on http://bit.ly/AAPDchairsideguide

About the authors

Michael Dhesi is a GDP who qualified in 2012 with BDS(Hons) from the University of Glasgow and has subsequently completed MFDS RCPS(Glasg) and an MSc in Advanced General Dental Practice at the University of Birmingham. Michael’s focus is in minimally invasive and adhesive restorative dentistry. He also has interests in the management of dental anxiety and oral surgery.

Clive Schmulian qualified from Glasgow University in 1993. Throughout his time in general dental practice, he has developed his clinical skills by obtaining a range of postgraduate qualifications, which in turn led him to develop an interest in digital imaging in both surgical and restorative dentistry. He is a director of Clyde Munro.

We are all too aware that mouth cancer is on the rise. More and more cases are being diagnosed every year with about 300,000 cases of lip and oral cancer reported globally1. In 2014, there were 7,680 cases of oral cancer in the UK2 and, since 1970 there has been a 93 per cent increase in the number of cases3.

Scotland remains a hot spot for oral cancer with higher incidence rates and lifetime risk compared to the rest of the UK.

Cancer Research UK predicts a further 33 per cent increase in oral cancer by 20353. Clearly, we need to act now to address this increasing problem. We, as a profession, have it within our power to do something; stand up, speak out and make some noise about mouth cancer. Our training and position in the community make us the ideal group of health care professionals to provide counsel to patients on risk reduction, screen for the disease and to empower patients with skills and knowledge to find the disease themselves at an early stage.

Risk factors

Traditionally, this has been a disease that affected older men. They have often smoked tobacco and drunk alcohol for many years. Now, that picture is beginning to change. Smoking and alcohol still remain important risk factors but more young people and women are developing this disease without traditional risk factors. Nine out of 10 cases of mouth cancer can be linked to a preventable cause4. Other risk factors include a diet low in fruit and vegetables, poor oral hygiene and the Human Papilloma Virus infection.

With global migration increasing it is likely we will see an increase in the use of smokeless tobacco, areca nut and betel quid in Scotland. There is also growing evidence of the adverse effect that shisha smoking has on health5. Therefore, we must think beyond the traditional risk factors.

A recent study revealed that the vast majority of patients developing head and neck cancer in Scotland are from the most deprived areas in our communities, therefore suggesting that this is a disease of inequality6. In fact, the deprivation gap for mouth cancer is the third highest amongst all cancers at 117 per cent7. Public health initiatives should take this into account when developing measures to address the burden of mouth cancer.

Prognosis

Dentists need to be vigilant when examining and screening our patients; we should have clear protocols and pathways in place for managing suspicious lesions and reviewing those lesions or mouths that simply ‘don’t look right’. Early detection is still recognised as the most important prognostic factor in mouth cancer8. Other prognostic factors include the aggressive nature of the tumour and the proliferation rate of the cells9.

Currently, the mainstay treatment for mouth cancer is high morbidity surgery. As a result of such major surgery, patients’ quality of life post surgery is vastly reduced. Treatment impacts on all aspects of life that we take for granted, such as enjoying meals, conversing freely and showing affection to loved ones. Although there have been great advances using free flap tissue repair to reconstruct surgical excision sites, this has had little to no impact on survival and prognosis, with only 53 per cent of patients surviving to five years post diagnosis10. Those that receive an early diagnosis have an 80-90 per cent chance of survival at five years. While those that present late with advanced disease have a much lower survival or if there is spread to other body systems then treatment is likely to be palliative.

Mouth cancer referral guidance

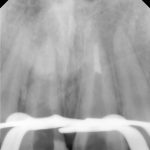

Dental patients should be examined for signs of malignancy as a part of the routine oral examination at every visit. The Scottish Referral Guidelines for suspected oral cancer11 identify a number of signs and symptoms which may represent malignancy (see Table 1 below). The guidelines recommend that those patients who present with the identified signs and symptoms which last for more than three weeks should be referred urgently to a specialist service according to local referral protocols.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence12 (NICE NG12) make similar recommendations and advise that patients who are referred urgently with suspected cancer should be given an appointment in the specialist service within two weeks of referral.

To improve early detection and thus survival, Scottish-based charity Let’s Talk About Mouth Cancer (LTAMC) work directly with the public as well as with professional groups. We advocate a shorter timescale than three weeks, instead recommending that patients should be referred urgently when signs and/or symptoms which are suspicious of mouth cancer do not resolve after just two weeks. The aim of this initiative is to reduce diagnostic delay as much as possible.

Diagnostic delay

Patient delay and professional delay contribute to the total diagnostic delay.

Patient delay

This is defined as “the period between the patient first noticing symptoms and their first consultation with a health care professional concerning those symptoms”13.

Approximately 30 per cent of patients diagnosed with mouth cancer will wait three months following the self discovery of signs and symptoms before attending a doctor or dentist14, 15. This may be because they attribute the symptoms to non-malignant, self-correcting conditions.

A study by Scott et al (2008)13 found that patients with better knowledge of signs and symptoms of mouth cancer are less likely to delay seeking advice. Knowledge about mouth cancer aids interpretation of symptoms and the decision to seek help. The same study also found that a low socio-economic background and deprivation are significantly higher in patients who delay seeking help. These patients also experience real or perceived limited ability to access healthcare. Some of the work of LTAMC aims to rectify some of these issues by educating the public about the signs and symptoms of mouth cancer, focusing on deprived and minority community groups.

Professional delay

It has been shown that lack of knowledge by general dental and medical practitioners about the signs, symptoms and risk factors of mouth cancer can also contribute to the delay in diagnosis. Patients will frequently present first to their doctor with mouth symptoms. A cross-sectional study in Dundee found that, compared to dentists, a significant number of doctors felt they had insufficient knowledge about the detection and prevention of mouth cancer16. Waiting lists and pressures in the health service may also contribute further to professional delay.

How to spot mouth cancer

As recommended in the guidelines, every patient attending for routine check-up should have a full head and neck soft tissue examination. A systematic approach should be routinely used to avoid missing any areas. A video of this can be seen on our website (www.ltamc.org/professional-resources).

Before any examination, a detailed history should be taken. For each area of concern, the patient should be asked about the length of time they have been aware of the lesion/symptoms and ascertain if there has been any pain, change in sensation or effect on function (speech, swallowing, eating). In many cases, however, early and even late tumours can be asymptomatic. It is also worth asking if a lesion has been present before and healed fully or partially. Of course, if the patient is unaware of the area, then questioning may be delayed until after detecting a suspicious lesion.

Extra-orally, the soft tissues should be checked for any asymmetry, swellings or lymphadenopathy; it is important to note any changes in texture and fixation. A hard, fixed lump in the neck is highly suggestive of tumour spread to the lymph nodes.

Intra-orally the oral mucosa has natural variation according to its anatomical site. It is important to be familiar with normal appearances as any changes need to be investigated. The Scottish Cancer Referral Guidelines11 recommend referral for cancer arising from the oral mucosa when there are persistent unexplained lumps, ulceration, unexplained swellings, red or mixed red and white patches of the oral mucosa. Proper and clear description of any lesion is fundamental, both for the sake of good record keeping and also to allow any referral to be as fulsome and informative as possible.

To cover all aspects of a lesion, these characteristics should be recorded and described:

- Site – where the lesion is, note adjacent structures

- Size – can be measured in millimetres with probe/ruler or relative to local anatomy (e.g. extending from mesial 34 to distal 36)

- Colour – red, white or mixed (homogeneous/heterogeneous)

- Texture – hard or soft, fixed or mobile, smooth or rough, induration

- Border – well or poorly defined, raised or flat.

Based on all these findings, a decision must be made whether to monitor in practice, make a routine referral or to refer urgently. It is not necessary to arrive at a definitive diagnosis, rather a decision to refer for further investigation and appropriate treatment. The patient should be informed of the findings, possible diagnosis and also the reasoning for referral or monitoring in practice. The importance of attending arranged appointments must be stressed.

Referrals quiz

Let’s take a few examples and put this into practice. Look at each of the cases below and their brief history. Try describing each as you would for a referral and decide whether you would monitor in practice, make a routine referral or refer urgently. Have a guess at the diagnosis as well. Remember, the triaging surgeon ultimately decides from your referral whether to allocate as urgent or routine, so quality of information is key.

Many lesions are not clear cut and easy to decide on management. You are not alone – if in doubt, seek the opinion of a colleague or send in a referral. In this case, the description and history you submit is essential for the receiving surgeon to adequately assess the urgency for appointment. Be reassured that the majority of urgent referrals after investigation are not cancerous but it is only possible to know that after appropriate tests.

It is vital to follow up a patient where the decision to monitor a lesion within practice or a routine referral has been made. In the instance there are any changes to the area, reconsider if the original decision needs to be altered. Likewise, when managing a lesion in practice first (e.g. ease traumatic denture, smooth sharp edge on tooth, prescribe antifungals), this must be reviewed after two weeks to gauge response. If not healed, then reappraise the suspected cause, treatment provided and potentially send a referral. Also, if the patient misses an appointment or has not received one within the expected time frame, contact the department to ensure one is arranged.

- Case one – Patient: Female, 34, with no symptoms, all feels soft. Clinical description: Stellate reticular white lesion, right buccal mucosa, adjacent to amalgam restoration.

- Case two – Patient: Male, 61, no pain, present for more than three weeks. Smoker. Soft on palpation. Clinical description: Well defined but non-homogenous mixed white and red lesion on dorsum of tongue.

- Case three – Patient: Female, 59, no pain but changed speech for one month. Clinical description: Right lateral tongue raised rolled margins with necrotic centre, firm and fixed on palpation. Hard fixed lumps felt in right neck.

- Case four – Patient: Male, 45, of Asian origin, painful large sore areas for more than three weeks, history of tobacco chewing. Clinical description: Large area of exophytic-type (cauliflower-like growths) affecting maxillary alveolus.

- Case five – Patient: Male, 46, non-painful lesion for one to two weeks. Clinical description: Asymptomatic gingival 3mm in diameter, sessile papillomatous-like lesion.

- Case six – Patient: Female, 55, painful mouth for more than three weeks. Clinical description: Well defined 2cm lesion on floor of mouth with raised rolled margins with necrotic centre, firm and fixed on palpation. Associated left neck swelling.

(Quiz answers are at the end of the article)

Empowering our patients

Recently, LTAMC has developed its strategy away from clinician-based screening in favour of patient empowerment – the focus has changed to teaching self examination for mouth cancer. Although a conventional oral examination by a clinician remains the most sensitive and specific method to detect mouth cancer cases17, teaching mouth cancer self examination empowers patients to recognise pathology in their mouth and may increase awareness.

A Cochrane review published in 2013 found that mouth cancer self examination had similar sensitivity and specificity to breast self examination17. Teaching mouth cancer self examination can be used as a tool in general practice to increase awareness of mouth cancer. It can form part of a general discussion about the signs, symptoms and risk factors of mouth cancer. The thorough, logical mouth self examination process follows five simple steps and is demonstrated in the graphic above. The key messages are to check for: red or white patches; lumps in the mouth that grow; ulcers in the mouth that do not heal; and persistent soreness/discomfort.

The advice is to attend the dentist or general medical practitioner if any of these signs/symptoms do not resolve in two weeks and importantly, to alert the practitioner to a concern about mouth cancer. Patients should be encouraged that mouth self examination is easy, and only requires a light source and a mirror. The aim is simply to empower patients to recognise normal tissues, and to present early if something changes. The mantra “If in doubt, check it out” should be repeated often.

LTAMC has also produced an instructive video aimed at teaching the general public how to perform a mouth cancer self examination. It can be found at youtu.be/WQaujHXauso

The video has been viewed more than 4,500 times in the UK, USA, Japan, Vietnam and India, indicating a worldwide interest. As mentioned above, a recent study has shown that approximately 30 per cent of patients with mouth cancer delay seeking help following discovery of symptoms for more than three months13. As early diagnosis is a key factor for improving prognosis and survival, we as dentists must tackle the lack of recognition of symptoms among our patients.

Lack of insight into initial symptom interpretation and lack of knowledge of mouth cancer have been shown to be significant variables which contribute to patient delay in seeking help13, and are issues that may be easily modified with targeted interventions by general dental practitioners.

Conclusions

Mouth cancer is increasing at an alarming rate and yet large sections of the public know little of the risk factors or signs and symptoms of the disease. Despite the fact that about half the population attend a dentist regularly for dental check-ups, many cases present at a late stage with a correspondingly poor prognosis. Survival has not improved substantially in the past 50 years and there is no treatment available that can transform the poor survival of someone with late stage disease to the much better survival of someone with early stage disease; the only thing that can do this is early diagnosis.

The work of LTAMC is firmly focused on teaching the public as well as professionals to diagnose mouth cancer early. We hope to break down health inequalities and empower as many people as possible to recognise the disease and its risk factors to improve survival. We call it our empowerment journey, so “Let’s talk about mouth cancer!”

Quiz Answers:

Case one

Outcome: Monitor in practice.

Diagnosis: Lichenoid lesion/lichen planus.

Case two

Outcome: Urgent referral.

Diagnosis: Dysplastic lesion or early cancer.

Case three

Outcome: Urgent referral.

Diagnosis: Squamous cell carcinoma.

Case four

Outcome: Urgent referral.

Diagnosis: Squamous cell carcinoma.

Case five

Outcome: Routine referral.

Diagnosis: Human Papillomavirus related papilloma.

Case six

Outcome: Urgent referral.

Diagnosis: Squamous cell carcinoma.

About the authors

This article was co-authored by the five trustees of the Scottish charity Let’s talk about mouth cancer (SC045100):

- Dr Niall McGoldrick BDS MFDS RCPS(Glasg), specialty registrar in dental public health.

- Mr Ewan MacKessack-Leitch BDS(Hons) MFDS RCPS(Glasg), GDP, Fife.

- Dr Stephanie Sammut FDS (OS), MClinDent, MOral Surg, MFDSRCPS,

consultant oral surgeon. - Dr Orna Ni Choileain BDS(Hons) MFDS RCSEd, medical student,

Trinity College Dublin. - Prof Victor Lopes PhD FRCS, consultant maxillofacial surgeon.

Website: www.ltamc.org

Twitter: @couldbeUrmouth

Facebook: www.facebook.com/letstalkaboutmouthcancer

References

1. N Johnson, A Chaturvedi: Global burden of oral cavity and pharyngeal cancers, Global Oral Cancer Forum: 2016

2. C R Smittenaar, K A Petersen, K Stewart, N Moitt. Cancer incidence and mortality projections in the UK until 2035. Br J Cancer. 2016 Oct 25; 115(9): 1147–1155

3. www.cancerresearchuk.org [Internet]. 2017 Available from:

www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/oral-cancer#heading-Zero

4. www.cancerresearchuk.org [Internet]. 2017 Available from:

www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/head-and-neck-cancers/risk-factors#heading-Zero

5. Ziad M El-Zaatari, Hassan A Chami, Ghazi S Zaatari Health effects associated with waterpipe smoking. Tob Control. 2015 Mar; 24(Suppl 1): i31–i43.

6. Purkayastha M, McMahon AD2, Gibson J, Conway DI. Trends of oral cavity, oropharyngeal and laryngeal cancer incidence in Scotland (1975-2012) – A socioeconomic perspective. Oral Oncol. 2016 Oct; 70-5. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.08.015. Epub 2016 Aug 31.

7. www.cancerresearchuk.org [Internet]. 2017 Available from

www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/incidence/deprivation-gradient#heading-One

8. Gómez, I., Seoane, J., Varela-Centelles, P., Diz, P. and Takkouche, B. (2009), Is diagnostic delay related to advanced-stage oral cancer? A meta-analysis. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 117: 541–546. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00672.x

9. Warnakulasuriya S. Prognostic and predictive markers for oral squamous cell carcinoma: The importance of clinical, pathological and molecular markers. Saudi J Med Med Sci 2014;2:12-6

10: www.cancerresearchuk.org [Internet ]Available from

www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/head-and-neck-cancers/survival#heading-Zero

11. Healthcare improvement Scotland. Scottish referral guidelines for suspected cancer 2013 ( updated in August 2014) available online

www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/our_work/cancer_care_improvement/programme_resources/scottish_referral_guidelines.aspx [last accessed 31 July 2017]

12. National Institute for health care and excellence. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral – NICE Guideline NG12. 2015 (last updated July 2017) available online www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12/resources/suspected-cancer-recognition-and-referral-pdf-1837268071621 [last accessed 31 July 2017]

13. Scott S, McGurk M, Grunfeld E. Patient delay for potentially malignant oral symptoms. Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116 2:141–147.

14. Scott SE, Grunfeld EA, McGurk M. Patient’s delay in oral cancer: a systematic review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34 5:337–343.

15. Allison P, Locker D, Feine JS. The role of diagnostic delays in the prognosis of oral cancer: a review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 1998;34 3:161–170. [PubMed]

16. Carter L, Ogden GR Oral Cancer awareness of general medical and general dental practitioners Br Dent J. 2007 Sep 8;203(5):E10; discussion 248-9. Epub 2007 13 Jul.

17. Walsh T, Liu JLY, Brocklehurst P, Glenny AM, Lingen M, Kerr AR, Ogden G, Warnakulasuriya S, Scully C. Clinical assessment to screen for the detection of oral cavity cancer and potentially malignant disorders in apparently healthy adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 11.

I’ve been teaching in the area of child protection and dentistry for approximately eight years and completed a masters by research in 2013 on Oral Disease in Vulnerable Children and the Dentist’s Role in Child Protection1. I’m now doing a PhD looking at what is involved in the decision by dental team members to refer suspected cases and how serious game methodology might support this context.

What is clear to me is that often decisions in this area are difficult and uncomfortable to make, so this article looks at what is expected of us as members of the dental team (whether we are dentists, dental nurses, therapists or technicians) and what this means from a practical point of view in our daily working lives.

The General Dental Council states that all members of the dental team “must raise any concerns you may have about the possible abuse or neglect of children” and “must know who to contact for further advice and how to refer concerns to an appropriate authority”2. They also state “you must find out about local procedures for the protection of children” and “you must follow these procedures if you suspect a child or vulnerable adult might be at risk because of abuse or neglect”2.

These wide-ranging statements mainly cover child protection (defined as activities undertaken to protect specific children who are suffering, or are at risk of suffering significant harm) but also bring in elements of safeguarding (defined as measures taken to minimise the risk of harm to all children).

From a practical point of view, there is the need to identify what your concerns are. This could be anything from unexplained (or inadequately explained) injuries, concerns about dental neglect, concerns about general neglect, a general lack of engagement with dental services to witnessing a child being physically abused in your waiting room or surgery. It is the vast spectrum of these concerns which make it difficult to provide what so many people ask for – a step-by-step guide for any conceivable situation – because there are so many different situations that could present themselves.

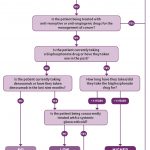

Some health boards have produced flowcharts for dental teams to follow and there is also a summary flowchart available on the Child Protection and the Dental Team website which are very helpful3. For some of these situations, the dental team members that I have been privileged to speak to (during my research and teaching) find the decision of what to do next straightforward, but for other situations it is more difficult.

It has already been well documented that there remains a 26 per cent gap between the proportion of general dental practitioners who have suspected child abuse or neglect in one or more of their paediatric patients (37 per cent) and the proportion that have referred suspected cases (11 per cent)4. Quantitative methods have consistently shown that the gap between dentists who suspect and refer in Scotland is affected by lack of certainty of the diagnosis, fear of violence to the child, fear of consequences to the child from statutory agencies, lack of knowledge of referral procedures, fear of litigation, fear of violence to the general dental practitioner and concerns of impact on dental practices4, 5.

So, let’s explore four of the most common things I’m asked about and hopefully it will be helpful to all of the team.

1. The child with caries whose family don’t engage with services

I’m asked about this situation a lot, probably because it is a common occurrence. We know caries is still common in children and statistics say 94 per cent of children in Scotland are registered with a general dental practitioner, with 85 per cent having seen their dentist in at least the last two years6. Perhaps a dentist has referred a patient for extractions under general anaesthetic but the patient is never taken to the assessment appointment and the dentist gets a letter back from the public dental service or the hospital dental service discharging them back to their care because they’ve not managed to see them.

Or perhaps it is a family that come for their check-ups but don’t bring the children back to have their treatment completed, or ones who repeatedly cancel, or don’t book check-ups when they get their reminder letters and the dental teams only end up seeing them sporadically. Or it may be children who have required extractions under general anaesthesia for removal of all their primary teeth but then don’t come back until they are aged seven or so and now have unrestorable caries in all their permanent molars.

These situations are difficult and all of them are examples of dental neglect, which is defined by the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry as “the persistent failure to meet a child’s basic oral health needs, likely to result in the serious impairment of a child’s oral or general health or development”7. Although dental caries is still common in children, signs such as failing to complete courses of dental treatment, failing to listen and act on preventive advice given by dental teams, children returning in pain repeatedly, children requiring repeated general anaesthetics due to dental issues or children who are repeatedly not brought to their dental appointments, are all concerning patterns of behaviour which are likely to result in the impairment of a child’s oral or general health or development7,8.

Untreated dental caries may be one of the first signs of child abuse or neglect9. Neglect should be considered if parents have access to, but persistently fail to obtain treatment for their child’s tooth decay10. Research also suggests that abused/neglected children are more likely to have untreated decayed teeth, significantly more dental plaque and gingival inflammation than non-abused/non-neglected children11–13.

Many practitioners whom I have spoken to then say: “Well if I have to refer every patient like that, I would be referring at least 60 per cent or more of my paediatric cohort!” This really depends on what practitioners mean by the term ‘refer’. All of these situations do require some action to be taken, but not all will necessitate an immediate referral to social work. There is very sensible advice given for this type of scenario in Child Protection and the Dental Team (CPDT) which recommends a three-level response to concerns about dental neglect, namely preventive dental team management, preventive multi-agency management, child protection referral3.

Preventive dental team management involves “raising concerns with parents, offering support, setting targets, keeping records and monitoring progress. The initial focus should be on relief of pain accompanied by preventive care. In order to overcome problems of poor attendance, dental treatment planning should be realistic and achievable and negotiated with the family”3. This is often all that is required and, in reality, is probably what most dental teams do on a day-to-day basis (although there is no evidence from research to prove this is the case).

Fully implementing a preventive dental team management strategy can have impacts on a practice and those impacts will have to be discussed as a team, for example deciding who will deal with contacting the family if agreed appointments are cancelled or missed. The CPDT website gives an example of how it might be put into practice3. The areas where research has suggested dental teams could improve upon are ‘setting targets’ and ‘monitoring progress’14. If this level of response to the concerns is not working or there is a breakdown of communication or the child/family has more complex needs then preventive multi-agency management may be more appropriate.

Preventive multi-agency management involves liaising with other professionals who might be involved with the family. Examples of other professionals could include the health visitor (for pre-school children), the general medical practitioner, the child’s social worker (if they already have one) or the child’s named person. The aim of this liaison is “to see if concerns are shared and to clarify what further steps are needed”3. There is a sample letter to a health visitor freely available on the CPDT website which can be used to assist with multi-agency working for children under five years old3.

A joint plan of action should be agreed (for example as a dental practice we will arrange appointments on these dates and the child’s social worker will facilitate attendance, or the health visitor will arrange a home visit by a dental health support worker to facilitate registration and attendance at our dental practice). A date should be specified for review of the action plan so that it can be checked that progress is being made.

If there is any point in the processes above where things begin to deteriorate, or if it is felt at any time that the child is at risk of suffering significant harm (this can include things like a child being in pain for more than a couple of days due to toothache and this is happening on more than one occasion), then any member of the dental team can make a child protection referral. Some dental team members struggle to work out when things become significant. A good rule of thumb can be that if you wouldn’t let children in your own circle of family or friends go through it, then it is probably significant.

Child protection referrals should be made according to the local procedures of where you work. In Scotland, a child protection referral is made either to the police or local children’s social work team (referrals can also be made to the Children’s Reporter but follow your local guidelines). If you do not already know your local contact numbers you can, currently, find them out by visiting www.withscotland.org/public-local-councils and typing in the postcode of the child you are concerned about. (Please note: This website address is likely to change in the future as WithScotland no longer exists, but many of their functions have been taken over by the new Centre for Child Wellbeing and Protection www.stir.ac.uk/ccwp/)

- Caries in children can be evidence of neglect at home

2. How do I make a child protection referral?

The majority of child protection referrals will involve a telephone call to your local social work office (Children and Families office ideally but in many areas in Scotland you will go through Social Care Direct) in the first instance explaining your concerns and stating you wish to make a child protection referral. Write down the names and job titles of everyone you speak to. The telephone referral should then be followed up in writing normally within 48 hours. This may involve completion of a shared referral form, or notification of concerns form (same form just different names), or similar, with one copy going into the child’s dental notes, one copy sent to the social work office that you spoke to on the phone, and, depending on your local procedures, another copy may be sent to your local child protection unit (CPU) or similar (or you may just have to notify your CPU by email or phone).

3. Will the family know I’ve referred them?

The short answer to this is that they might. In most situations it is best practice to tell the family what your concerns are and why you are referring them to social services but there will, of course, be some situations where the family don’t know, either because you can’t get in contact with them or you may believe that you would put the child in more danger if the family were aware of the referral.

You can refer anonymously but, bear in mind that if the concerns you have are related to non-attendance with you or concerns about something dental, then even if you refer anonymously the family will, probably, be able to work out where the referral came from so it is a much better situation if you have informed them the referral is being made.

4. I’m worried about how the family will react

Many dental professionals assume telling a family you are going to contact social work will be bad news, but for some families it will be the first time anyone has actually offered them any help. As members of the dental team, we quite often have to break bad news to our patients (e.g. “I’m sorry I can’t save the tooth, it needs to be extracted”). Being concerned is a natural human response but it is helpful to think through all the reactions that you would be worried about and how, as a team, your practice will manage them.

For example, if the family are angry and choose to de-register from your practice, you can’t always prevent that from happening but you would want to pass that information on to the other agencies involved such as the social work office you referred to. I suggest being quite clear in your practice about what your professional responsibilities are and having posters or information up in waiting areas promoting that you take the safeguarding of children and vulnerable adults seriously.

Many dental team members have told me they are worried that as they live in a small town that word will spread, or their own children will be targeted at school or they will be threatened by the families involved. My advice is that if you are threatened, inform the police and relevant social work office involved. If your own children get picked on because of rumours, approach the school as you would do about any episode of bullying your child may experience and talk to your child about the nature of your job (e.g. “You know mummy/daddy is a dentist/dental nurse/practice manager and looks after people’s teeth, but I also have a responsibility to make sure the children that I see at work are alright and are being looked after properly”). If your practice gets branded as “the ones who call social work”, take this as a good thing as it means you are actively looking out for and promoting the welfare of your paediatric patients. There are many experts out there who can give advice on how to use it as a

‘practice builder’.

Conclusion

Ultimately, it is not only our professional responsibility, but also an ethical responsibility to protect and safeguard those in society who can’t do it for themselves. Doing nothing when you have a concern is never an option – you would probably continue to worry and you cannot predict what the impact on the child would be.

Unfortunately, I have had to look at statements from dental team members when something awful has happened to one of their paediatric patients, and so often there have been warning signs (e.g. multiple missed appointments, failure to complete treatment) but the dental teams did not record or raise any concerns. Clearly I have the benefit of hindsight and experience but my hope is that as more dental teams think about and practise looking out for the wellbeing of their paediatric patients, then perhaps I’ll see fewer awful things happening. Or, if they are still happening, I’ll see real evidence that the dental teams involved did everything they could to help the child.

About the author

Christine Park is a senior clinical university teacher at Glasgow Dental Hospital and School, and honorary consultant in paediatric dentistry at NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde.

References

1. Harris CM. Oral disease in vulnerable children and the dentist’s role in child protection [MSc Thesis] Glasgow: University of Glasgow; 2013. Available at: http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4150/1/2013harrismsc.pdf.pdf Accessed 03/08/2017

2. General Dental Council. Standards for the Dental Team. Guidance on Child Protection and Vulnerable Adults. GDC; 2013. Available at www.gdc-uk.org/professionals/standards/team Accessed 03/08/2017

3. Harris J, Sidebotham P, Welbury R et al. Child protection and the dental team. An introduction to safeguarding children in dental practice. Sheffield: Committee of Postgraduate Dental Deans and Directors, 2006. Available at: bda.org/childprotection Accessed 03/08/2017

4. Harris CM, Welbury, R, Cairns, AM. The Scottish dental practitioner’s role in managing child abuse and neglect. Br Dent J 2013; 214(E24):1–5. Available at: dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.435 Accessed 03/08/2017

5. Cairns AM, Mok JYQ, Welbury RR. The dental practitioner and child protection in Scotland. Br Dent J 2005; 199(8):517–520; discussion 512; quiz 530–531.

6. ISD Scotland. Dental Statistics – NHS Registration and Participation. A National Statistics Publication for Scotland; 2017. Available at:

www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Dental-Care/Publications/2017-01-24/2017-01-24-Dental-Report.pdf?49161928893 Accessed 03/08/2017

7. Harris JC, Balmer RC, Sidebotham PD. British Society of Paediatric Dentistry: a policy document on dental neglect in children. Int J Paediatr Dent 2009. Available at: http://bspd.co.uk/Portals/0/Public/Files/PolicyStatements/Dental%20Neglect%20In%20Children.pdf Accessed 03/08/2017

8. Balmer R, Gibson E, Harris J. Understanding child neglect. Current perspectives in dentistry. Prim Dent Care 2010; 17: 105–109.

9. Blumberg ML, Kunken FR. The dentist’s involvement with child abuse.

NY State Dent J 1981; 47:65–69.

10. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (2009). When to suspect child maltreatment: full guidance. Clinical Guideline 89. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: London. Available at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg89/evidence/cg89-when-to-suspect-child-maltreatment-full-guideline2 Accessed 03/08/2017

11. Greene PE, Chisick MC, Aaron GR. A comparison of oral health status and need for dental care between abused/neglected children and non-abused/non-neglected children. Pediatr Dent 1994;16:41-45

12. Valencia-Rojas N, Lawrence HP, Goodman D. Prevalence of early childhood caries in a population of children with history of maltreatment. J Public Health Dent 2008;68(2):94-101

13. Montecchi PP, Di Trani M, Sarzi Amadè D, et al. The dentist’s role in recognizing childhood abuses: study on the dental health of children victims of abuse and witnesses to violence. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2009; 10(4):185-187.

14. Harris JC, Elcock C, Sidebotham PD, Welbury RR. Safeguarding children in dentistry: 2. Do paediatric dentists neglect child dental neglect? Br Dent J 2009;206: 465 – 470

In 2011, the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) published clinical guidance on the Oral Health Management of Patients Prescribed Bisphosphonates. This was in response to reports in the literature describing a rare side effect in patients treated with these drugs, bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ)1.

Bisphosphonates are prescribed to reduce bone resorption in patients with osteoporosis and other non-malignant diseases of bone and to reduce the symptoms and complications of metastatic bone cancer. The drugs persist in the body for a significant period of time; alendronate has a half-life in bone of around 10 years2. As dental extractions appeared to be a risk factor for this oral complication, there was a need for guidance providing clear and practical advice for dentists in primary care on how to provide care for patients prescribed these drugs.

Since 2011, several other drugs have been implicated in what is now referred to as medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). The condition has been observed in patients treated with the anti-resorptive drug denosumab which, like the bisphosphonates, is indicated for the prophylaxis and treatment of osteoporosis and to reduce skeletal-related events associated with metastasis. Another drug class implicated in MRONJ is the anti-angiogenics, which target the process by which new blood vessels are formed and are used in cancer treatment to restrict tumour vascularisation. At the time of writing, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has published Drug Safety Updates warning of the risk of MRONJ for three anti-angiogenic drugs: bevacizumab, sunitinib and aflibercept3,4.

Development of the updated SDCEP guidance

In response to these developments, SDCEP convened a second guidance development group (GDG) in 2015 to update the guidance. The GDG included consultants of various dental specialities, primary care dental practitioners, medical specialists and two patient representatives, who provided feedback on patient views and perspectives.

Pre-publication research was carried out by TRiaDS (Translation Research in a Dental Setting, www.triads.org.uk), who work in partnership with SDCEP, including a national survey of users of the first edition of the guidance and interviews with dentists, pharmacists and doctors. The findings informed the updating of the guidance and have been used as the basis for an implementation questionnaire and a national research audit.

A systematic and comprehensive search of the literature was conducted to inform the recommendations in the guidance. The quality of the evidence and strength of each of the key recommendations is stated clearly in the guidance with a brief justification in the accompanying text. A more in-depth explanation of the evidence appraisal and formulation of recommendations is provided in an accompanying methodology document.

NICE has accredited the process used by SDCEP to produce Oral Health Management of Patients at Risk of Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw, which means users can have high confidence in the quality of the information provided in the guidance. Accreditation is valid for five years from 15 March 2016. More information on accreditation can be viewed at www.nice.org.uk/accreditation

Prior to publication, the guidance was scrutinised through external consultation and peer review and it is endorsed by several of the Royal Colleges, Public Health England and Department of Health (Northern Ireland).

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw

MRONJ was first reported by Marx in 20031 and is defined as exposed bone, or bone that can be probed through an intraoral or extraoral fistula, in the maxillofacial region that has persisted for more than eight weeks in patients with a history of treatment with anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs, and where there has been no history of radiation therapy to the jaw or no obvious metastatic disease to the jaws5. Risk factors include the underlying medical condition for which the patient is being treated, cumulative drug dose, concurrent treatment with systemic glucocorticoids, dentoalveolar surgery and mucosal trauma. It is important to note that MRONJ is a rare side-effect of treatment with anti-resorptive and anti-angiogenic drugs and, although invasive dental treatment is a risk factor, it does not cause the disease.

At present, the pathophysiology of the disease has not been fully determined and current hypotheses for the causes of necrosis include suppression of bone turnover, inhibition of angiogenesis, toxic effects on soft tissue, inflammation or infection5. It is likely that the cause of the disease is multi-factorial, with both genetic and immunological elements.

Incidence

Estimates of incidence and prevalence vary due to the rare nature of MRONJ. It appears clear that patients treated with anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs for the management of cancer have a higher MRONJ risk than those being treated for osteoporosis or other non-malignant diseases of bone. This is likely to be due, in part, to the substantially larger doses of the drugs that cancer patients receive.

For patients being treated with anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs for the management of cancer, the risk of MRONJ approximates 1 per cent5–9, which suggests that each patient has a one in 100 chance of developing the disease. However, the risk appears to vary based on cancer type and incidence in patients with prostate cancer or multiple myeloma may be higher.

For patients taking anti-resorptive drugs for the prevention or management of non-malignant diseases of bone (e.g. osteoporosis, Paget’s disease), the risk of MRONJ approximates 0.1 per cent or less2,5,7, 10–17, which suggests that each patient has between a one in 1,000 and one in 10,000 chance of developing the disease (Table one).

Patients who take concurrent glucocorticoid medication or those who are prescribed both anti-resorptive and anti-angiogenic drugs to manage their medical condition may be at higher risk.

The incidence of MRONJ after tooth extraction is estimated to be 2.9 per cent in patients with cancer and 0.15 per cent in patients being treated for osteoporosis18.

Risk factors

As outlined previously, the most significant risk factor for MRONJ is the underlying medical condition for which the patient is being treated. Dentoalveolar surgery, or any other procedure that impacts on bone, is also a risk factor, with tooth extraction a common precipitating event19–22. However, MRONJ can occur spontaneously without the patient having undergone any recent invasive dental treatment.

The MRONJ risk in patients who are being treated with bisphosphonates is thought to increase as the cumulative dose of these drugs increases. One study found a higher prevalence of MRONJ in osteoporosis patients who had taken oral bisphosphonates for more than four years compared to those who had taken the drugs for less than four years13. There is currently no evidence to inform an assessment of MRONJ risk once a patient stops taking a bisphosphonate drug. Therefore, it is advised that patients who have taken bisphosphonate drugs in the past should continue to be allocated to the risk group they were assigned to at the time the drug treatment was stopped.

The effect of denosumab on bone turnover diminishes within nine months of treatment completion14, 23. Therefore, patients who have stopped taking denosumab should be considered to still have a risk of MRONJ until around nine months after their final dose. Anti-angiogenic drugs are not thought to remain in the body for extended periods of time.

Chronic systemic glucocorticoid use has been reported in some studies to increase the risk for MRONJ when taken in combination with anti-resorptive drugs20, 24–27. The combination of bisphosphonates and anti-angiogenic agents has also been associated with increased risk of MRONJ20, 28. The risk appears to be increased if the drugs are taken concurrently or if there has been a history of bisphosphonate use.

Despite these risk factors, the majority of patients are able to receive all their dental treatment in primary care, with referral only appropriate for those with delayed healing.

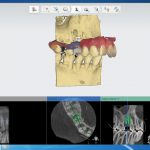

- Fig 1 – SDCEP Oral Health Management of Patients at Risk of Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw guidance

- Fig 2 – Assessment of patient risk

- Fig 3 – Managing the oral health of patients at risk of MRONJ

Guidance recommendations

The aim of the SDCEP guidance is to assist and support primary care dental teams in providing appropriate care for patients prescribed anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs and to encourage a consistent approach to their oral health management. The guidance also aims to empower dental staff to provide routine dental care for this patient group within primary care thereby minimising the need for consultation and referral to secondary care.

Risk assessment

The guidance advises practitioners to assess and record whether a patient taking anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs is at low risk or higher risk of developing MRONJ based on their medical condition, type and duration of drug therapy and any other complicating factors. An up-to-date medical history is therefore essential in identifying those patients who are, or have been, exposed to the drugs and to identify any additional risk factors, such as chronic use of systemic glucocorticoids. Careful questioning of the patient may be required, along with communication with the patient’s doctor, to obtain more information about the patient’s medical condition and drug regimen(s).

The low-risk category includes those patients who have been treated for osteoporosis or other non-malignant diseases of bone with bisphosphonates for less than five years or with denosumab and who are not taking concurrent systemic glucocorticoids. The higher risk category includes cancer patients and also those being treated for osteoporosis or other non-malignant diseases of bone who have other modifying risk factors. Figure two illustrates how risk should be assessed for each individual patient.

The risk of MRONJ should be discussed with patients but it is important that they are not discouraged from taking their medication or from undergoing dental treatment. The guidance includes details of the points which should be covered in such a discussion and patient information leaflets are also available to facilitate this dialogue. As with all patients, the risks and benefits associated with any treatment should be discussed to ensure valid consent.

Initial care

Ideally, patients should be made as dentally fit as feasible before commencement of their anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drug therapy. However, it is acknowledged that this may not be possible in all cases and in these situations, the aim should be to prioritise preventive care in the early stages of drug therapy. Due to their increased MRONJ risk, it is particularly important that cancer patients undergo a thorough dental assessment, with remedial dental treatment where required, prior to commencement of drug therapy. It may also be appropriate to consider consulting an oral surgery or special care dentistry specialist for advice on clinical assessment and treatment planning for these medically complex patients.

As part of this initial management, patients should be given personalised preventive advice to help them optimise their oral health. The importance of a healthy diet, maintaining excellent oral hygiene and regular dental checks should be emphasised and patients should be encouraged to stop smoking and limit their alcohol intake where appropriate. They should also be advised to report any symptoms such as exposed bone, loose teeth, non-healing sores or lesions, pus or discharge, tingling, numbness or altered sensations, pain or swelling as soon as possible.

The guidance recommends prioritising care that will reduce mucosal trauma or may help avoid future extractions or any oral surgery or procedure that may impact on bone. Radiographs should be considered to identify possible areas of infection and pathology and any remedial dental work, such as extraction of teeth of poor prognosis or treatment of periodontal disease, should be undertaken without delay. It may also be appropriate to consider prescribing high fluoride toothpaste for these patients.

Continuing care

Recommendations for continuing care advise practitioners to carry out all routine dental treatment as normal and to continue to provide personalised preventive advice in primary care. For low-risk patients, straightforward extractions and other bone-impacting treatments can be performed in primary care. A more conservative approach is advised in higher risk patients, with greater consideration of other, less invasive alternative treatment options. However, if extraction or other bone-impacting procedure remains the most appropriate course of action, these can be carried out in primary care in this patient group. There is no benefit in referring low or higher-risk patients to a specialist or to secondary care based purely on their exposure to anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs and it is likely to be in patients’ best interests to be treated wherever possible by their own GDP in familiar surroundings.

There is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of antibiotic or topical antiseptic prophylaxis specifically to reduce the risk of MRONJ following extractions or procedures that impact on bone29–32. Extraction or oral surgery sites should be reviewed, with healing expected by eight weeks. Evidence of delayed healing at eight weeks should be considered a sign of possible MRONJ. Figure three outlines the management of patients prescribed anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs.

Management of patients with suspected MRONJ

The treatment of MRONJ is beyond the scope of the guidance and patients with suspected MRONJ should be referred to a specialist in line with local protocols. Signs and symptoms of MRONJ include delayed healing following a dental extraction or other oral surgery, pain, soft tissue infection and swelling, numbness, paraesthesia or exposed bone. Patients may also complain of pain or altered sensation in the absence of exposed bone. Although the majority of cases of MRONJ occur following a dental intervention that impacts on bone, some can occur spontaneously. A history of anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drug use in these patients should alert practitioners to the possibility of MRONJ.

Guidance format

The main SDCEP guidance document provides practical advice and recommendations to inform the assessment of the patient’s MRONJ risk, the optimisation of their oral health during the initial phase of drug treatment and their ongoing care. A supplementary Guidance in Brief, which summarises the main recommendations, is also available.

Additional tools have been developed to support the implementation of the guidance, including patient information leaflets and information for prescribers and dispensers. The aim of the patient information leaflets is to make patients aware of the risk of MRONJ, the importance of continuing to take their medication and ways they can reduce their MRONJ risk. The leaflets provide a basis for further communication between the patient and their dentist and, ideally, should be provided to patients identified as being at risk of MRONJ at the commencement of their

drug treatment.

The guidance and the supporting documents are freely available via the SDCEP website (www.sdcep.org.uk).

Future research

MRONJ is a rare condition and consequently there is a lack of high-quality evidence on which to base guidance recommendations. High-quality research studies are required to determine the efficacy of MRONJ prevention protocols, both in the context of routine dental care and in those patents who require an extraction or procedure which impacts on bone. As an adverse drug reaction, MRONJ is monitored by the MHRA (www.mhra.gov.uk) and dental practitioners are encouraged to notify the MHRA of any suspected cases via the Yellow Card Scheme (www.yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk).

Reporting is confidential and patients should also be encouraged to report via the scheme.

It should be noted that the use of anti-angiogenic drugs in cancer is an expanding field, and it is likely that any future medications with these modes of action may also have an associated risk of MRONJ. The establishment of a national database to monitor cases of MRONJ could inform some of the research areas highlighted above and may also serve to identify other drugs which could be implicated in the disease.

As with all its guidance publications, SDCEP plans to review the recommendations in this guidance three years after publication and revise them if new evidence or experience emerges and indicates that this is appropriate.

About the author

Samantha Rutherford is a research and development manager for guidance development within the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP). She has led the development of a number of SDCEP guidance projects and was the project lead for the Oral Health Management of Patients at Risk of Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw guidance, which was published in 2017. Samantha has a PhD in medicinal chemistry and prior to her involvement in guidance development, she was a research scientist in the pharmaceutical industry.

References

1. Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2003;61(9):1115-7.

2. Khan SA, Kanis JA, Vasikaran S, Kline WF, Matuszewski BK, McCloskey EV, et al. Elimination and biochemical responses to intravenous alendronate in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1997;12(10):1700-7.

3. MHRA. Aflibercept (Zaltrap): Minimising the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Drug Safety Update. Apr 2016;9(9).

4. MHRA. Bevacizumab and sunitinib: Risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Drug Safety Update. Jan 2011;4(6):A1.

5. Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, Goodday R, Aghaloo T, Mehrotra B, et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw -2014 update. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2014;72(10):1938-56.

6. Khan AA, Morrison A, Hanley DA, Felsenberg D, McCauley LK, O’Ryan F, et al. Diagnosis and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw: a systematic review and international consensus. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2015;30(1):3-23.