Globally since 2009, Candida auris, a fungal species closely related to Candida albicans, has been responsible for a number of drug-resistant hospital-acquired fungal infections. Though C. auris is yet to be isolated from the human oral microbiome, 10 years since its discovery in Japan, what can the UK dental profession learn about antimicrobial stewardship and the prescription of anti-fungal agents from this lesser-known ‘superbug’?

Over my last four years as a dental student, the importance of antimicrobial stewardship and best practice when prescribing antimicrobial agents has been a key focus of my clinical training.

Where antimicrobial resistance remains a growing threat to public health in the UK1, the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme’s (SDCEP) clinical guidance document: ‘Drug Prescribing for Dentistry’2, is a valuable resource to General Dental Practitioners (GDPs) in protecting against the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in Primary Dental Care. Despite this guidance and the fact that the overprescription of broad-spectrum antibiotics can lead to a reduction in their therapeutic efficacy3, the similar threat of anti-fungal drug resistance in Dentistry is less reported within the dental literature.

Amongst the many microbial species that colonise the oral cavity, C. albicans is the most common of species within its genera4. Though often co-existing as a harmless commensal microbe, acute and chronic episodes of immunosuppression can lead to candidal overgrowth and symptoms of opportunistic oral or systemic candidiasis4.

In such cases, GDPs may quickly reach for the prescription pad, prescribing an anti-fungal agent such as the polyene nystatin (oral use) or the azoles miconazole (topical use) or fluconazole (oral & systemic use)5.

However, the overuse of antifungal agents, like antibiotics, can similarly confer multi-drug resistance6,7. As resistant strains of candida can have adverse effects on respiratory and gastrointestinal health upon colonisation of their respective epithelia8,9,10, could drug-resistant strains of candida, such as C. auris, pose a threat to the health of susceptible patients in General Dental Practice?

To date, C. auris is yet to be established as part the human oral microbiome, first isolated from the ear of an elderly patient in Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital (Japan) in 200911,12.

A close derivative of C. albicans, in the 10 years since its discovery, C. auris has been identified as a global cause of numerous life-threatening cases of fungaemia in hospital-based patients11,12; the strain also linked to several hospital infections in the UK13.

Interestingly, as global warming and the overuse of azole antifungals in the agricultural industry and global medical setting have been cited as a possible causes for the emergence of this multi-drug resistant fungus11,12,14, similar resistant fungal strains may also develop if anti-fungal agents are overprescribed, or used prophylactically in dentistry.

This is particularly important as the use of azoles in the UK, two of the three licensed anti-fungals in the Dental Practitioners’ Formulary5, appear to have grown over recent years15.

So, what lessons can the dental profession learn from the emergence of C. auris as a nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infection?

Firstly, ensuring that clinical audit, addressing the appropriateness of antimicrobial prescribing, includes antifungals, as well as antibiotics, should be encouraged; assessing how far local prescribing habits match SDCEP guidance2.

Similarly, as advocated when treating oral bacterial infections, local measures should always be considered before prescribing any antimicrobial agent.

For example, as described by SDCEP2, in the case of the candidal infection denture stomatitis, establishing the likely cause of fungal overgrowth and remedying this, e.g. educating patients in the improvement of denture hygiene, should be a first-line approach when managing oral fungal infections.

Arguably, the suggestions above should already form part of everyday clinical practice. However, a difficulty faced in promoting antimicrobial stewardship within NHS Dentistry is ensuring that GDPs are best placed to make such changes, i.e. have access to the necessary tools and funds to implement best practice recommendations.

For example, the National Institute of Clinical Healthcare Excellence’s (NICE) guidance [NG15]: Antimicrobial stewardship: systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine16, suggests that in the case of persistent antimicrobial infections, oral microbiological sampling techniques should be encouraged to improve the specificity of diagnoses and thus the appropriateness of an antimicrobial prescription.

Though an example of active antimicrobial stewardship that could be useful in identifying drug-resistant fungal strains, the likely costs, need for additional training, the lag time between diagnosis and prescription and the storage and transport of microbiological samples to and from a clinical laboratory that has the appropriate facilitates to process such a request, are potential barriers to such a programme.

In the meantime, it seems prudent that dental advisory committees like SDCEP and dental schools should continue to advocate best prescription practice, emphasising the more inclusive term of ‘antimicrobial resistance’ over ‘antibiotic resistance’ in guidance documents and teaching; ensuring that GDPs and students are well aware that all modes of antimicrobial agents, available for prescription, are sensitive to drug resistance.

With this, although available for free, increasing the ‘appeal’ of NICE’s antimicrobial prescribing guidance16 as an opportunity for verifiable CPD or making such information more ‘user-friendly’ as part of an app or interactive resource for GDPs, the latter pioneered by SDCEP2 and the Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group (SAPG)17, may be of benefit in increasing both readership and compliance with such guidance; especially important since antimicrobial prescribing is not yet recognised by the General Dental Council (GDC) as one of their ‘highly recommended CPD topics’18.

Ten years on from the first case of a C. auris infection in Japan, the exact threat of this drug-resistant fungus in primary care dentistry remains unknown.

However, research into resistant microbial biofilms is ever-increasing – notably, the work of Professor Ramage’s team at the University of Glasgow who were the first in the UK to demonstrate the ability of C. auris to form a biofilm in vitro19; a feature which may further complicate the management of C.auris infections with anti-fungal agents.

Encouraging steps considering that the spread of anti-fungal resistance poses a tangible threat to dental and general public health, it is hoped that this article emphasises the importance of evidence-based and appropriate anti-fungal prescriptions, acknowledging that – if Scotland and the rest of the UK want to remain at the forefront of dental antimicrobial stewardship – improving the ease at which the recommendations from clinical guidance documents can be implemented in primary care by UK-based GDPs is a key, and timely, next step.

About the author

Alex Farrow-Hamblen is a final year student at Carlisle Dental Education Centre / School of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Central Lancashire.

Useful resources

- Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness programme – Drug Prescribing for Dentistry Dental Clinical Guidance app

- Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group – Antimicrobial companion app

- National Institute of Health Care Excellence Antimicrobial stewardship: systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine use (2015)

References

- Public Health England. Antimicrobial Resistance. Online information available. (accessed 17 August 2019)

- Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Drug Prescribing for Dentistry Dental Clinical Guidance – Third Edition. Dundee: NHS Education for Scotland. 2016. ISBN: 978-1-905829-28-6

- World Health Organisation. Antibiotic Resistance. Online information available. (accessed 17 August 2019)

- Akpan A, Morgan R. Oral candidiasis. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2002. 78: 455-459.

- National Institute of Health Care Excellence. Dental Practitioners’ Formulary: List of dental preparations. Online information available (accessed 17 August 2019)

- Tumbarello M, Tacconelli E, Caldarola G, Morace G, Cauda R & Ortona L. Fluconazole resistant oral candidiasis in HIV-infected patients. Oral diseases. 1997. 3: 110-120

- Niimi M, Firth NA & Cannon RD. Antifungal drug resistance of oral fungi. Odontology. 2010. 1: 15-25.

- De Pascale G & Antonelli M. Candida colonization of respiratory tract: to treat or not to treat, will we ever get an answer? Intensive Care Medicine. 2014. 40: 1381-1384

- Yousef S, Perry J & Shah D. Risk factors for candida blood stream infection in medical ICU and role of colonization – A retrospective study. Isolated Candida infection of the lung. Respiratory Medicine Case Report. 2015. 16: 18-19.

- Kumamoto CA. Inflammation and gastrointestinal Candida colonization. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2011. 14: 386-391.

- Casadevall A, Dimitrios P & Kontoyiannis VR. On the Emergence of Candida auris: Climate Change, Azoles, Swamps, and Birds. American Society for Microbiology: mBIO. 2019. 10.

- Lone SA & Ahmad A. Candida auris-the growing menace to global health. Mycoses. 2019. 62: 620-637.

- Public Health England. Candida auris – a guide for patients and visitors. Online information available. (accessed 18 August 2019)

- Casadevall A, Kontoyiannis DP & Robert V. On the Emergence of Candida auris: Climate Change, Azoles, Swamps, and Birds. American Society for Microbiology: mBIO .2019. 10(4)

- Oliver RJ, Dhaliwal HS, Theaker ED & Pemberton MN. Patterns of antifungal prescribing in general dental practice. British Dental Journal. 2004. 196: 701-703.

- National Institute of Health Care Excellence Antimicrobial stewardship: systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine use [NG15]. 2015. Online information available (accessed 18 August 2019)

- Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group. Antimicrobial companion app. Online information available (accessed 18 August 2019)

- General Dental Council. Recommended CPD topics. Online information available (accessed 18 August 2019)

- Sherry L, Ramage G, Kean R, Borman A, Johnson EM, Richardson MD, et al. Biofilm-forming capability of highly virulent, multidrug-resistant Candida auris. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2017. 23(2): 328–331.

[ Words: Ilyaas Rehman, BDS (Glas) ]

Introduction

Introduction

This case report documents the treatment provided for a very anxious patient at APCO Dental Care, Lanark. The case demonstrates the importance of some fundamental basics of dentistry: effective communication and empathy, anxiety management, treatment planning and a team-approach. I was honoured to win the VDP case presentation prize for the West 6 scheme and I would like to thank those who aided along the way.

Background

A 41-year-old anxious female patient attended the practice for an examination in February 2019; the first time in nine years. She complained of a broken tooth in the lower right side, which was presently asymptomatic but felt sharp to the tongue. In addition to this, the patient was aware of the poor condition of her remaining dentition, stating that she was unable to eat or socialise confidently. She alerted us to using Superglue to hold her remaining crowns in, and teeth together.

The patient was now keen to try to rehabilitate her dentition and therefore, the motivating factors for her attendance were:

- Embarrassment: unable to socialise confidently, unable to smile without covering her mouth.

- Function: unable to eat hard or crunchy foods, insufficient posterior teeth to chew with.

- Poor quality of life.

In addition to this, the famous Lanark Lanimer week was approaching. This traditional celebration is highly anticipated among locals and provided a realistic timeframe for treatment.

Medical, dental and social history

The patient informed us of having multiple sclerosis and hypertension, which were being controlled by Interferon and Amlodipine respectively. She reported previous asthma, for which medication was no longer required. She also reported taking Fluoxetine, Lansoprazole, Thyroxine and Dihydrocodeine. The patient could not remember the last time she attended the dentist, however, computer records confirmed this to be nine years ago.

She reported having several bad experiences in the past which have amounted to severe general dental anxiety. She brushed twice daily with a manual toothbrush and was not presently using any interdental aids or mouthwashes.

She worked full-time as a veterinary nurse. She quit smoking six to seven years ago after smoking roughly 20 cigarettes a day for 20 years (20 pack years) and reported zero alcohol consumption.

Examination

No abnormalities were detected on extra-oral examination.

Intra-orally, the patient’s soft tissues showed no abnormalities. The patient was partially dentate with a heavily restored remaining dentition, including failing crowns. The occlusal relationship was class 1 and there was lack of posterior occlusal support. Oral hygiene was poor, with evidence of generalised gingivitis and plaque. Despite this, the present BPE scores did not exceed 2s. A fractured 44 amalgam was observed, and a temporary filling was placed here prior to further radiographic and clinical assessment.

There was also evidence of excess material across the upper anterior teeth, which the patient informed us of being Superglue to hold in the crowns. Application of firm digit pressure to the upper anterior teeth caused mobility of 2-3mm of the entire sextant. Caries was recorded clinically in teeth 13, 11, 21, 44, 31 and 33. There was also presence of several retained roots.

Due to the clinical findings, periapical radiographs and clinical photographs were taken.

A list of diagnoses was subsequently established:

- Generalised gingivitis.

- Generalised Periodontitis Stage II Grade B – currently stable – risk(s): ex-smoker.

- Primary caries: 13, 31.

- Secondary caries: 11, 21, 44, 33.

- Defective restorations: UR2, UL2.

- UR1 previously RCT with asymptomatic PAP.

- UR4 retained root, previously RCT with asymptomatic PAP.

- LR3 vertical fracture, previously RCT with asymptomatic PAP.

- UL4 retained root with asymptomatic PAP.

Treatment options

Aims of treatment were to restore health, function and aesthetics. Four possible avenues were discussed:

- Deconstruing the upper anterior segment, reassess and potentially restore: Re-RCT 11 12 22 and restore with post-core crowns.

– Caries removal and restoration. Extraction of retained roots and LR3.

– Provision of upper and lower immediate partial dentures. - Extraction of all teeth of poor prognosis – 13, 12, 11, 21, 22 and retained roots. Provision of immediate upper and lower partial dentures

– Caries removal and restoration. - Extraction of all teeth of poor prognosis, implant approach to restoring gaps, caries removal and restoration.

- Referral to specialist service (NHS/Private).

Each option was discussed in detail. Following this, the patient initially opted to try option one, despite understanding the plethora of risks attached and the poor prognosis of the remaining teeth. However, further probing revealed this was due to a severe anxiety of extractions.

Appropriate evidence-based anxiety management techniques were discussed, including desensitisation, acclimatisation and in-house IV sedation. The patient subsequently made an informed decision to proceed with option two. All items of treatment were to be carried out under the NHS, excluding the LR4 due to lack of mechanical retention for amalgam.

Treatment

E/O frontal view

E/O lateral view

I/O maxillary view

I/O mandibular view

E/O retracted frontal view

A staged treatment plan was proposed as follows:

- Immediate – Temporisation of fractured LR4.

- Initial

– Hygiene Phase Therapy: OHI (tipps), diet advice, supragingival scale.

– Extractions under IVS: 13, 12, 11, 21, 22, 43 and retained roots 14, 24, 47, 34.

– Provision of immediate upper and lower partial acrylic dentures.

– Caries removal and restoration: LR4, LL1, LL3. - Re-evaluation.

- Reconstruction

– Provision of new upper and lower partial dentures. - Maintenance.

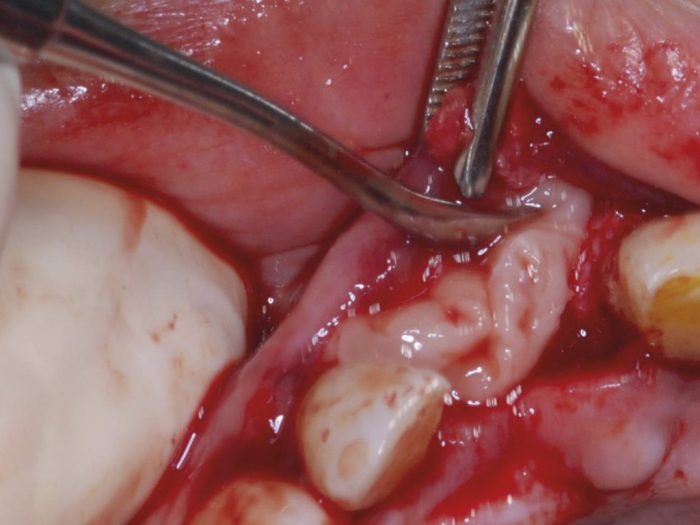

The patient showed exceptional motivation to overcome anxiety and strive towards a healthier oral environment. There were two key problems encountered with treatment. Firstly, extraction of 47, 43 and 34 required a surgical approach. This was carried out in-house on the same appointment with assistance and therefore was rectified accordingly. Secondly, the patient found that she was unable to tolerate the lower denture. However, rather than this being due to the lower denture fitting poorly and uncomfortably, the patient felt she would prefer to firstly get accustomed to the upper denture alone. In effect, the patient was functioning with a modified shortened dental arch.

Periapical lower left

Periapical lower anterior

Periapical Upper Anterior ii

Periapical Upper Anterior i (G2 coned off)

Periapical upper right

Subsequent to completion of the initial treatment, the patient returned with irreversible pulpitis associated with 35 and root canal therapy was carried out.

Pre-operative conclusion

The patient expressed thorough delight with the result of the treatment carried out and has, as a result, developed trust with the practice and treatment providers. She is now able to interact and socialise confidently, smile freely and eat healthily.

Pre-operative

Post operative

Though arguably no part of this treatment plan is especially complex, this case has been a thorough learning experience in the management of an anxious patient. With the assistance of senior colleagues, I was able to provide the patient with an outcome that we are both very pleased with.

I believe that, as a result of implementing basic principles successfully from the onset, the patient has regained her trust in the profession.

This case report documents the treatment provided for a very anxious patient at APCO Dental Care, Lanark. The case demonstrates the importance of some fundamental basics of dentistry: effective communication and empathy, anxiety management, treatment planning and a team-approach.

I was honoured to win the VDP case presentation prize for the West 6 scheme and I would like to thank those who aided along the way.

Consultation represents the next step on the journey towards achieving a more effective system of CPD

Some dental professionals feel that CPD is little more than a tick-box exercise,” says Rebecca Cooper, the General Dental Council’s Head of Policy and Research. Last month, the GDC published a consultation document inviting ideas, comments, and views on the short and long-term future of professional learning and development in dentistry.

It follows the GDC’s launch last year of ‘Enhanced CPD’, its new model of continuing professional development. Some of the changes ECPD brought included the introduction of a personal development plan (PDP) to help record CPD activity and aid further development; a change in the number of CPD hours required (100 hours for dentists, 75 hours for hygienists, therapists, clinical technicians and orthodontic therapists and 50 hours for nurses and technicians); and doing away with the need to submit non-verifiable CPD.

“While the Enhanced CPD scheme made some good progress towards increasing professional ownership of CPD and placing greater emphasis on reflection and planning,” adds Rebecca, “we know a more supportive model of learning can be achieved to provide dental professionals with the information and tools they need to meet and maintain high professional standards and quality patient care.

“Our proposals look at how we might move to a system that is flexible and responsive for the full range of dental professionals and where professionals can increasingly take responsibility for their own development, without the need for heavy-handed enforcement. This discussion document represents a significant milestone in achieving this goal and we really want to hear from as many people as possible about where lifelong learning should go from here.”

The discussion document is presented in three parts: a future model for lifelong-learning which seeks views on a portfolio model and the merits of continuing with set CPD hour requirements; CPD practices, and how professionals can be encouraged to take up more high-value activities, such as peer learning and reflection; and informing CPD choices, which asks about the insights and intelligence dental professionals refer to when selecting learning activities and how these can be improved and promoted.

The publication represents the next step on the GDC’s journey towards achieving a more effective system of CPD. That journey began with commitments made in the regulator’s 2017 publication Shifting the Balance and the introduction of the Enhanced CPD scheme last year. Since then, this journey has continued with the gathering of further information and evidence through stakeholder feedback, a systematic literature review on CPD and, most recently, through workshops with professional associations, educators and other regulators which took place earlier this year.

After building a robust base of evidence, the GDC says it wants explore ideas for developing the CPD scheme with dental professionals and stakeholders and that it is “opening a conversation” about what meaningful CPD is, how it can be achieved, and what the obstacles might be that prevent dental professionals from accessing and undertaking it.

The literature review synthesised relevant articles and outlined the approach other professionals are taking. It provided the GDC with evidence, which can support its development of a more qualitative approach to the delivery and monitoring of CPD for the dental workforce. The aim was to inform and strengthen GDC policy development for dental CPD that would promote registrants’ sense of ownership and pride in their continuing educational achievements and in turn improve engagement between the regulator and the dental workforce.

It concluded that aspects of qualitative-based models which could form part of an outcomes-focused model for dental UK professionals include: emphasis on reflection and reflective practice, active learning, portfolios, peer (and mentor) interaction and feedback; development of online, user-friendly tools, enabling registration of required evidence; a well-designed change and implementation process; reinforcement of close engagement of registrants with regulators through easily accessible communication channels; quality-assurance mechanisms embedded in the model, valuable for both regulators and registrants.

“If the aspiration is to create motivation across all registrants to actively pursue meaningful, relevant CPD activities,” said the review, “then of course the approach to CPD should promote the concept of a responsible professional, who takes pride in keeping up to date and enhancing their clinical and professional skills and sharing their experience with others.”

References

The document can be read here.

Responses and views can be submitted until 3 October.

Scott J F Wright, Dental Core Trainee, Glasgow Dental Hospital & School

ABSTRACT: The use of preformed metal crowns (PMCs) or stainless steel crowns (SSCs) within paediatric dentistry is widely accepted. Predominantly, this is for the treatment of carious primary molars. This article aims to increase readers’ awareness of the use of PMCs for permanent molars in a paediatric population.

Introduction and background

The majority of treatment of paediatric patients in the UK is carried out by general dental practitioners. It is therefore crucial that GDPs are aware of treatment options for these patients.

Preformed metal crowns (PMCs) were first described by Engel in the 1950s1. Primarily, their use has been for the restoration of primary molars that have caries or structural defects. There is a large and growing body of evidence to suggest that primary teeth restored with PMCs are less likely to develop problems or cause pain in the long term than those primary teeth restored with conventional restorations.2 Teeth that were restored using the Hall Technique were also shown to give less discomfort at the time of placement than conventional restorations.2 There is wide acceptance of this technique to restore primary molars in both the United States and United Kingdom.3, 4

There is less evidence and information surrounding the use of PMCs for permanent molars , but they can be a useful addition to the armamentarium of any dentist treating paediatric patients. Permanent molars of poor prognosis can interfere with eating, sleeping, attending school, and taking part in daily activities. 8, 9, 10 Children can experience pain and infection, as well as a reduction in their overall quality of life.9, 10 Additionally, retention of permanent molars of poor long-term prognosis can be beneficial orthodontically. RCS England guidelines suggest that the ideal time for extraction of first permanent molars is between eight and 10 years old.13 PMCs can be helpful in assisting with this and prolong the retention of molars that would otherwise be lost.

Dean et. al6 found that about 48 per cent of Scottish GDPs assessed in their study were already using PMCs with the Hall Technique for the management of caries in primary molars. Anecdotally, however, there is limited knowledge of GDPs surrounding the use of PMCs in the permanent dentition.

As mentioned above, there is a comparative limited body of evidence to support use of SSCs in permanent molars to that of primary molars. In 2016, a study in the US suggested that use of permanent tooth SSCs as an interim restoration resulted in an 88 per cent success rate, with an average lifespan of 45.18 months in all age groups. This result was statistically significant in the under-nine age group (P=0.001). However, this was a small sample size.

PMCs are valuable in the interim management poor prognosis permanent molars. This article aims to give GDPs an introduction to the use of PMCs in the permanent dentition for paediatric patients. Many of the principles and skills used in restoration of primary molars with PMCs can be applied to permanent teeth.

Indications for use of PMCs in permanent molars

There are many clinical circumstances in which PMCs for permanent molars can be a useful treatment choice. Paediatric patients can present with difficult clinical scenarios that require operative intervention due to caries or structural defects in these teeth. This can be further complicated by social factors including parental or guardian wishes, child anxiety and medical history.

- Multi-surface caries in permanent molars where use of composite or amalgam is contra-indicated

- Pre-co-operative or anxious child precludes conventional restoration

- Structural defects such as molar-incisor hypomineralisation, amelogenesis imperfecta, dentinogenesis imperfecta

- Temporary restoration until definitive treatment accepted such as extraction for orthodontic purposes.

Of benefit is the limitation to caries progression and reduction in symptoms that can be achieved through use of PMCs.

Contraindications for use of PMCs in permanent molars

There are relatively few contraindications to the above.However, below are some aspects that require consideration.

- Nickel allergy – stainless steel crowns is in fact a misnomer as PMCs are constructed with nickel chromium

- Insufficient tooth structure to retain crown

- Signs or symptoms of irreversible pulpitis

- Peri-apical pathology.

Technique for placement of PMCs in permanent molars 2, 11, 12

The technique for placement of PMCs in permanent molars is very much dependent on compliance of the child patient. Many previous articles advocate the use of conventional preparations however, the use of a modified ‘Hall Technique’ approach can also be used.

Pre-treatment preparation

- Explain the treatment to patient and guardian, obtaining informed consent.

- Place orthodontic separators, using two lengths of floss, three to five days before the scheduled appointment for fit of PMC

- Rehearse procedure with patient and guardian.

Treatment appointment – Placement

- Gauge initial size of PMC required by measuring mesio-distal distance of tooth and choosing the most appropriately sized crown

- Conduct minimal preparation including slight mesial-distal and minor occlusal reduction if appropriate or clinically possible,

- not required in all instances

- Remove caries with excavator or handpiece if appropriate or clinically possible, not required in all instances

- Adjust height of crown using crown scissors, the PMC should extend just to the ACJ of the tooth where possible, and slightly subgingivally (Figures 1a, 1b, 1c)

- Smooth rough edges with a polishing stone or disc

- Adjust margins of PMC with crimping or other orthodontic pliers to ensure a secure fit of the PMC cervically around the tooth (Figure 2)

- Practice seating of PMC with child after showing them the crown

- Sit the patient upright and protect the airway with gauze

- Isolate the tooth being treated appropriately to minimise moisture contamination

- Fill the adjusted PMC with resin-modified glass ionomer cement and seat firmly with thumb pressure, placing a cotton-wool roll occlusally

- Ensure the PMC is in the correct position and encourage the child to bite firmly onto the cotton wool roll, continually assessing the position of the PMC. Gamification in the form of asking the patient to play ‘tug of war’ or ‘biting down like a tiger’ can be helpful at this time while you ‘attempt to remove’ the cotton-wool roll.

Treatment appointment – Post-placement

- Remove excess cement with probe, excavator and knotted floss interproximally.

- Check final position, occlusion and gingival condition, gingival blanching is normal

- Give post-operative instructions, positive reinforcement and reward with a sticker.

Post-operative instructions

Post-operative instructions can be given that are very similar to those given when placing PMCs on primary teeth. Advise parents and children that occlusion will be slightly high but will settle within three to five days. Analgesia may be required, and paracetamol and ibuprofen, if not contraindicated, would be appropriate. Asking parents to reinforce positive messages between appointments is of benefit to developing co-operation, particularly if multiple PMCs are being placed.

Figure 1a Use of crown scissors to adjust the height of PMC

Figure 1b Further adjustment

of height of PMC

Figure 1c PMC, adjusted for height, with excess material that

should be disposed of in Sharps waste. Margins should then be adjusted.

Figure 2 Crimping of PMC margins following adjustment of height

Permanent Tooth PMCs

and Orthodontic Separators

Complications and troubleshooting

Complications can occur with all treatment and therefore it is key to ensure that after placement, PMCs are monitored clinically and radiographically to assess for signs of success and failure.

During placement, if the crown is deemed to be in the wrong position, it may be possible to remove it with an excavator before the cement sets. If this is not possible, removal can be performed by cutting a slot bucco-lingually across the occlusal surface of the crown, and extending this down the buccal aspect. The crown can then be peeled away using

an excavator.

Adapting the margins of PMCs on permanent molars is crucial. Failure to do so may result in secondary caries, periodontal disease or impaction of unerupted teeth.5, 11 The margins should sit tightly around the neck of the tooth to reduce the aggregation of plaque leading to the development of carious lesions or periodontal disease. Assessment clinically using a sharp probe, floss and bitewing radiographs should be conducted to determine success.

Conclusion

To conclude, the use of PMCs in paediatric patients should not simply be limited to primary teeth. PMC placement in permanent molars for a paediatric population should be part of the skillset of all GDPs in order to best manage clinical scenarios without the need for referral to specialist services. Development of this aspect of paediatric dentistry can only come with education and practice; the authors hope that this article can assist with this.

Scott J F Wright

The author wishes to express grateful thanks to Mrs Christine Park, Honorary Consultant in Paediatric Dentistry, Glasgow Dental Hospital & School, University of Glasgow.

References

- Engel RJ. Chrome steel as used in children’s dentistry. Chron Omaha Dist Dent Soc. 1950;13:255-258.

- Innes NPT, Ricketts D, Chong LY, Keightley AJ, Lamont T, Santamaria RM. Preformed crowns for decayed primary molar teeth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD005512. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005512.pub3.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Restorative Dentistry. Clinical Guidelines Reference Manual 2014; 36(6): 230−241.

- Kindelan SA, Day P, Nichol R, Willmott N, Fayle SA (2008), UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry: stainless steel preformed crowns for primary molars. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry, 18: 20-28. doi:10.1111/j.1365-263X.2008.00935.x

- Discepelo K, Sultan M. (2016) Investigation of adult stainless steel crown longevity as an interim restoration in pediatric patients. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 2017; 27: 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/ipd.12255

- Dean, A.A., Bark, J.E., Sherriff, A. et al. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent (2011) 12: 159. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03262798

- Taylor GD, Pearce KF, Vernazza CR.Management of compromised first permanent molars in children: Cross-Sectional analysis of attitudes of UK general dental practitioners and specialists in paediatric dentistry. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019;00:1 14. https://doi.org/10.1111/ipd.12469

- Taylor GD, Scott T, Vernazza CR. Research Prize Category: impact of first permanent molars of poor prognosis: patient & parent perspectives. Int J Pediatr Dent.2018;28(S1): 2-3.

- Sheiham A.Oral health, general health and quality of life. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(9):641-720.

- Shaikh S, Siddiqui A, Aljanakh M.School absenteeism due to toothache among secondary school students aged 16-18 years in the Ha’il Region of Saudi Arabia. Pain Res Treat. 2016;2016:7058390.

- Randall, R.C., 2002. Preformed metal crowns for primary and permanent molar teeth: review of the literature. Pediatric Dentistry, 24(5), pp.489-500.

- A comprehensive guide to achieving the best results with Prefabricated Crowns, 3M ESPE

- A Guideline for the Extraction of First Permanent Molars in Children by M.Cobourne, A.Williams & M.Harrison (update of the 2004 guideline by M.Cobourne, A.Williams & R.McMullan, previously updated in 2009)

- Evans D, Innes, NPT. The Hall Technique, Users Guide. A minimal intervention, child centred approach to managing the carious primary molar

Introduction

Implementing the best available evidence and enabling positive sustainable change in practice is an enviable goal for anyone providing healthcare services. In this final article of a three-part series, we will discuss applying the evidence and methods of evaluating the outcome, as the final two parts of taking an evidence-based approach. These final two parts are arguably the most important but are often perceived as the two most difficult to achieve.

In general dental practice there are any number of barriers to implementing effective change, including the healthcare system, the will of staff, patient expectations and time available. That said, this stage does not need to be overly complex but it does need to be planned and there are a number of tools we can use to deliver evidence-based dentistry to each and every patient. This article is focused on giving some practical advice and pointers.

Systems thinking

Any challenge is easier when it is broken down into smaller chunks. So think of what you are trying to achieve, then the process that takes place to get to that goal and the system it is part of. Everything we interact with is a system, and there are processes within that system. As soon as we walk out the door in the morning we begin to interact with systems and we start processes.

The footpath network is part of a national infrastructure system that we interact with, queuing for a coffee at the train station is part of a small local system, the surgery at work is a complex local system with many interacting and moving parts. Within these systems there are various different processes; for example, the footpath network has a series of pedestrian crossings, the process to crossing the road will often start by pushing a button and waiting for the green man on the traffic lights, but, of course, it is often a lot more complex than this.

In order to understand the system and how best to implement evidence within a system you need to be able to map the processes you are thinking of changing and determine what might influence the application of evidence. This is called process mapping. Once you have the map, then you can think about the possible barriers to applying the best evidence and equally think about what would enable application of best evidence. The ultimate system makes it easy to do the right thing without relying on humans to do so. Equally, an effective system can make it difficult to do the wrong thing.

Figure 1 illustrates how a process map for crossing the road might look. This map is very simple and doesn’t take into account all potential choices or influences, but it should give you an idea of how to go about constructing a process map (see below).

Let’s return to our clinical example of our paediatric patient in practice whose parent has withheld consent for fluoride varnish application. After completing parts 1,2 and 3 of an evidence-based approach, (1: Asking the right question, 2: Searching for the best available evidence, 3: Critically appraising the evidence), and based on the evidence found, we are confident that for this child, fluoride varnish application would be the best approach to prevent decay. The current barrier to you doing so is the lack of consent from the parent. We need a pragmatic solution to the problem, and providing the information only at the time of application at chair side may not be the best solution. There are many different elements of the system and processes that lead up to that point that could influence the outcome. The appointment booking, check-in, walking to the chair, interaction between you the child and the parent. How many members of staff have been parts of the process? Any change will need to take the system, processes and staff into account. Likewise, there have been a number of tools used, including IT, telephones and dental instruments that also need to be taken into account. A good way to visualise the process and possibly facilitate brainstorming sessions with staff is to again create a process map, similar to Figure 2 (below). This figure is quite obviously simplified, as in reality there are many more influences and choices!

So thinking of the system, the processes and the current barrier, how about if a leaflet had gone out with the appointment in advance that explained the benefits of the treatment to the parent, would it have helped? This could be a change idea to test out in the practice. There are a number of ways that you could implement and evaluate this change.

We will look at a few methods at our disposal. First: Quality improvement methodology.

What is quality improvement (QI)?

QI is an approach we can use to build change into processes and systems that is sustained. It is a new kid on the block in dentistry, but it has been around in healthcare for more than 30 years and for much longer in industry.

The first formal introduction to QI in Scottish dentistry was through the Scottish Patient Safety Programme

in 2016.

Our healthcare colleagues working in the acute and other Scottish primary care services have been doing QI for just over 10 years now. We have some catching up to do, but the benefit is that we can learn from those that have gone before. There are plenty of QI success stories published in a bespoke journal for QI, BMJ quality and safety.

QI methodology and science take a pragmatic approach to implementation of change in a system, focused on tests of change and clear measures so we understand the implications of any change. This controlled approach to implementing change is ideal for use in dental practices. QI is also ideal for finding ways to implement best practice that is supported by evidence.

There is a level of skill and knowledge required to maximise all the QI tools available. NES has developed a number of useful resources that can be accessed online to help navigate QI.

Changes to the SDR in October 2017 mean that dentists can now include quality improvement work where

this would have been traditionally audit activity.

Peer review

Another method to achieve the final two parts of an evidence-based approach might be to use peer review. This is a process of collaborative working with colleagues to establish a group that facilitates peer-to-peer discussion. It involves practitioners outside your practice and could bring a fresh point of view to the processes in your practice. NES has laid out some advice on the requirements of a peer review group on their website.

If done correctly this approach can be used to fulfil quality improvement hours.

One way to use peer review to improve care might be for discussion and implementation of the updated SDCEP guidance on paediatric dentistry that has recently been published1.

You could establish a local group of dentists to come together and discuss the guidance, using it as your standard of care and benchmarking against it, then working together to make changes that will benefit patients and improve the quality of care.

In our example of using a leaflet as a test of change, the practice down the road might have more success in winning parents over because they give the leaflet out with appointment letters rather than when they arrive at the reception desk. Or they might have more experience of paediatric dentistry and could share some tips on behavioural management and helping kids accept treatment.

Behaviour change models

Sometimes implementation can come up against a lot of barriers and it seems like there is no path through all the issues and reasons not to change. Susan Michie’s research group at University College London has produced a number of models and theories that could be helpful.

The TRIADS (translational research in a dental setting) team uses some of these methods alongside guidance development and implementation of SDCEP guidance 2. Thinking about barriers to change, it is sometimes down to the physical confines of the working environment or maybe it is the people within it. There are various methods for helping to work through the barriers and understand how to break them down and facilitate positive behaviour change.

The theoretical domains framework is made up of 14 domains that can help you understand what the barriers are by providing a framework to create questions from3.

For example, the first domain is knowledge, questions in this domain might look like: Do practitioners know that new SDCEP guidance for paediatrics has been published? The second domain is skills; a question in this domain might be: Do dentists in the practice know how to place a Hall crown?

Once you gain answers to these questions you can begin the frame ideas and develop facilitators that will enable application of evidence-based practice and guidance. That might be issuing each practitioner with the guidance and arranging a team meeting to discuss it, changing pro-formas on the surgery operating system to include risk assessments that hadn’t been previously included or arranging for the practice to have a training day on fitting Hall crowns. You can only come up with effective solutions if at first, you understand the real underlying barriers. You can read more about the TDF in a free open access journal.

Evaluating the outcome further

All of the approaches above have evaluation built in. The usual go-to mechanism for measuring and evaluating change tends to be a traditional style audit of pre- and post-intervention data collection. This is an effective method of evaluating an outcome, but it only gives a snapshot, usually of quantitative data, of an ongoing and dynamic system. This type of audit activity still has a place to ensure standards are met and identify areas where there could be improvements but we shouldn’t be restricted to it.

There are many other ways of evaluating outcomes and presenting evidence of effective change. It is important though, to distinguish between process measures and outcome measures. In the fluoride varnish example, a process measure might be the number of successful applications of varnish applied, but the outcome measure would be the reduction in caries rate or continued prevention of caries for the patient. Having the ultimate health outcome in mind throughout the project is important, as after all everything the project is striving to achieve is improve the quality of care we provide to patients and improve their health.

Qualitative feedback from staff on a new process is an important measure when evaluating outcomes and could be gathered in staff meetings or in questionnaire form. Staff often come up with pragmatic and innovative ideas that might not have been thought of previously.

Gathering patient feedback is another very valuable measure. The Scottish Government’s Health and Social Care standards provide some useful questions and themes to base outcome markers on 4. An example of the headline outcomes in the document are ‘I have confidence in the people who support and care for me’ and ‘I am fully involved in all decisions about my care and support’. The document is worth a read; the standards are meant to compliment already existing standards set out by various legislative bodies.

Staff and patient feedback could be combined with quantitative data as part of the evaluation of a project in your practice. Returning to QI, the method of quantitative data collection in QI uses a sustained approach to data collection. QI has a programme of active data collection taking place throughout the change process. Instead of collecting large amounts of data at two time points, QI asks that you collect smaller amounts of data at more regular time points. This provides greater levels of regular feedback that can help you understand the implications of any changes you have made earlier.

Conclusion

The three articles we have published in this magazine should give you a good basis for moving forward and practicing evidence-based dentistry. Providing high-quality care and sustaining it is the end goal. Backing up your clinical decision-making and informing your treatment plans with evidence will inevitably help you achieve that. Hopefully the top tips in these articles help you to do that.

If you are further interested in the implementation of evidence in practice and want to be part of testing ideas more formally, then the Scottish Dental Practice-Based Research Network will be of interest to you, check out their website to find out about their current projects how to get involved.

Authors

Niall McGoldrick BDS, MFDS RCPS(Glasg); Derek Richards BDS, FDS, MSc, DDPH,FDS(DPH)

References

- SDCEP. www.sdcep.org.uk. [Online] 2018. [Cited: July 20, 2018.].

- The translation research in a dental setting (TRiaDS) programme protocol. al, Jan E Clarkson et. 57, s.l. : Implementation Science, 2010, Vol. 5.

- A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Lou Atkins, Jill Francis, Rafat Islam, Denise O’Connor, Andrea Patey, Noah Ivers, Robbie Foy, Eilidh M.Duncan, Heather Colquhon, Jeremy M. Grimshaw, Rebecca Lawton, Susan Michie. 77, s.l. : Implementation Science, 2017, Vol. 12

- Scottish Government. Health and Social Care Standards. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government, 2017. 978-1-78851-015-8.

Abstract

A paediatric dental avulsion is not a clinical scenario that you will be faced with on a daily basis in general practice. Being confident in the steps required to manage a paediatric dental avulsion may reduce the stress of the situation and will allow for the most effective treatment to be provided in a timely manner. When managing a paediatric trauma, a clear, structured history and initial assessment will allow for the most appropriate treatment to be administered quickly, ensuring that no potential child protection concerns are missed. The initial assessment should establish; any head injury concerns, whom the child is with, the nature and timing of the injury and the child’s medical and tetanus status. The extra oral dry time and the stage of the tooth’s development will affect your subsequent management and the tooth’s long-term prognosis. This article is going to highlight the key factors that should be taken into consideration when assessing and managing an acute paediatric dental avulsion.

Introduction

The management of acute paediatric dental trauma within general practice doesn’t occur on a daily basis, so when it does occur it can be a daunting experience. The blood, tears & worried parents will inevitably create a more stressful encounter than a routine treatment appointment. Being confident in the initial history taking and clinical steps required to manage the patient’s care will reduce the stress and will improve the long-term prognosis of the damaged teeth. This article aims to highlight the key factors that should be considered when you are presented with a paediatric dental avulsion.

Twenty-five per cent of children experience dental trauma 1, ranging from concussion to complex dental trauma affecting multiple teeth. The maxillary incisors are most commonly affected, most commonly affecting the 7–14 age group. The main aetiology includes sport, falls and fights 2. Other factors that can increase an individual’s risk of dental trauma include; the presence of a skeletal overjet or incompetent lips 3,4.

Avulsions account for 0.5 – 3 per cent of dental trauma 5. Although they are not the most common form, they are associated with a poor long-term prognosis and the initial management can have a significant input towards the short and long-term outcomes 6,7.

From the moment the child walks through the surgery door, your initial assessment should commence. Key factors that have to be taken into consideration include; the risk of head injury, the child’s medical history and tetanus status, the nature of the injury, the time from the trauma to the replantation, the child’s social and dental history, whether the tooth has an open or closed apex, the storage medium and the risk of infection.

Having an extra oral dry time of less than an hour will significantly affect the tooth’s long-term prognosis and will influence the management of the avulsion. Furthermore, an open apex will significantly improve the tooth’s long-term survival. The loss of neurovascular blood supply to the pulp following an avulsion is detrimental to survival. The International Association of Dental Trauma (IADT) Guidelines recommends the elective root canal treatment of all permanent teeth with a closed apex to prevent infection

and resorption 8.

Non-accidental injury should also be kept in mind when assessing any child presenting with a dental trauma injury. A study looking at 390 clinical case records of children with suspected physical abuse showed that 59 per cent of children had orofacial signs of the abuse 9. It may be necessary to discuss the patient’s case with the child’s named person or with the local social work department. If you deem the child to be in imminent danger the case may require escalation to the local police service.

Head injury/airway

Has there been any associated head injury or loss of consciousness? Is the child conscious and breathing with no threat to their airway? Any concerns over potential head/ c-spine injury or any compromise to the patient’s airway will require attention from the local Emergency Department. Ask about any nausea, sickness or loss of memory that may have occurred since the time of injury and rule out these potential concerns at the start of the consultation.

Medical history

As with any consultation, any relevant medical conditions that may affect the subsequent management of the patient should be considered. Does the child have a bleeding disorder? Do they have any allergies to the metal wire you may plan to place or to the antibiotics you would consider prescribing? Are they asthmatic and already in distress over their current injury? If they are asthmatic, ibuprofen may not be an appropriate analgesia for when they are discharged home. If the child is immunosuppressed or has a cardiac defect immediate replantation may not be the most appropriate treatment option. Acute specialist input will likely be required.

These factors should all be considered before planning clinical treatment.

Haemostasis

Bleeding is often associated with dental trauma. This can be active bleeding or a clotted wound with a bloodstained face. Regardless of whether the bleeding is fresh or residual staining, this can be distressing for the patient and the accompanying adult. Active bleeding may be from a tooth socket or from an associated laceration. Once the source of the bleeding has been identified, haemostasis should be achieved through the use of local anaesthetic, pressure and sutures as required. This can be challenging if the child is already distressed. If the child has a bleeding disorder achieving haemostasis may be difficult. This may necessitate a prompt referral to secondary care.

History

When taking a history for a paediatric trauma case it is firstly important to establish who is with the child – parents, carers, teacher etc. Time should be taken to listen to the history provided from both the child and their accompanying adult.

It is very important to find out when the injury occurred. Time is of extreme importance when planning treatment and discussing prognosis. If the tooth has been avulsed, the transport medium should also be established: water, milk, saliva, dry?

Once aware of when the injury occurred it is important to carefully find out where and how the injury happened. Was the child accompanied at the time of the injury? Does the story match with the clinical presentation? Does the child’s account match the history provided by the accompanying adult? Was the environment clean or dirty? Clear documentation of this discussion is crucial.

It is important to compare the story with the injury to assess whether the two coincide. If the presentation is delayed find out if there is a legitimate reason for this delay in presentation. Follow the local practice policy to raise concerns if you are suspicious of the injury and associated circumstance. Under the new GIRFEC Guidelines, each child should have a named person. They can be contacted and the incident shared in a confidential manner if you are at all concerned.

When sharing information, the ‘golden rules’ should be followed 10:

- Adhere to the principles of the Data Protection Act 1998

- Share information that is necessary, relevant and proportionate

- Record why information has been requested or shared

- Make the child, young person or family aware of why information is being shared (unless there are child protection concerns).

Immunisations

Is the child’s tetanus up to date? They may require a booster if they are not up to date with their vaccinations or if it is out of date.

Standard vaccination protocol: The primary course of tetanus vaccination consists of three doses of a tetanus vaccination given within one-month intervals. At three years four months old the child should receive a tetanus booster. A second booster should then be given at age 14.

If in doubt, advise a medical review by their GMP.

Antibiotics

There is minimal evidence supporting the use of antibiotics following an avulsion. The prescription of antibiotics is at the discretion of the clinician. Factors that can influence this are highlighted in the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry Avulsion Guidelines 11.

- There has been additional contamination of the tooth or soft tissues.

- There is injury to multiple teeth, soft tissues or other parts of the body which may necessitate the need for antibiotics on their own or as a result of the combination of these injuries.

- To facilitate the safe delivery of subsequent surgery or

- The medical status may make the child more prone to infections.

Dental history

Find out the child’s level of dental anxiety, previous treatment and how likely they will cope with the required treatment. In this acute instance, the main priority is to replant the tooth as time efficiently as possible, if patient compliance will allow for this. It is also important to consider the subsequent treatment. If the patient is unlikely to cope with the treatment in general practice or if the treatment required involves specialist input, e.g. an MTA plug for an open apex, prompt referral will ensure no treatment delay is encountered.

Social History

When recording the child’s social history make a note of who they live with and which nursery/ school they attend. This information may be required if external services are being involved. Ensure they are registered with a GP and that you have their details.

Management

The International Association of Dental Traumatology (IADT) Guidelines 12, updated in 2012, give clear guidance on the management of paediatric trauma.

A summary is provided below:

General Trauma Advice

- A soft diet for one-two weeks depending on the nature of the trauma

- Avoidance of sports

- Continuing with oral hygiene measures, using a soft tooth brush

- The use of chlorhexidine mouthwash twice a day for seven days

- Analgesia – paracetamol and ibuprofen as required.

Deciduous Teeth

If a deciduous tooth has been avulsed don’t replant the tooth. Discuss with the child and the parents the potential risk of damage to the permanent successor. Discuss:

- Delayed eruption/failure of eruption

- Decalcification

- Discolouration.

Provide general trauma advice and arrange a review appointment.

Closed Apex

(Permanent teeth)

a) Tooth has been replanted prior to the patient’s arrival

- Clean the gingiva and surrounding area, ensuring there are no lacerations or associated injuries.

- Use clinical and radiographic assessment to ensure the tooth is in the correct position.

- Place a flexible splint which will be in place for two weeks.

- Assess tetanus status.

- Prescribe a course of antibiotics if deemed appropriate.

- Give general trauma advice.

- Start root canal treatment in 7–10 days.

b) Extra oral dry time <60mins

- Hold the tooth by the crown and gently clean the root surface using saline.

- Use local anaesthetic to provide suitable anaesthesia.

- Gently irrigate the socket.

- Assess for lacerations or loose bone.

- Replant the avulsed tooth gently back into the socket.

- Use clinical and radiographic assessment to ensure the tooth is in the correct position.

- Place a flexible splint which will be in place for two weeks.

- Assess tetanus status.

- Prescribe a course of antibiotics if deemed appropriate.

- Give general trauma advice.

- Start root canal treatment in 7–10 days.

c) Extra oral dry time >60mins

- Clean any soft tissue from the tooth’s root using gauze

- Root canal treatment can be carried out at this stage or following reimplantation

- Two per cent sodium fluoride solution can be used to soak the tooth for 20 min if you have this available

- Use local anaesthetic to provide suitable anaesthesia

- Gently irrigate the socket

- Assess for lacerations or loose bone

- Replant the avulsed tooth gently back into the socket

- Use clinical and radiographic assessment to ensure the tooth is in the correct position

- Place a flexible splint which will be in place for four weeks

- Assess tetanus status

- Prescribe a course of antibiotics if deemed appropriate

- Give general trauma advice

- Start root canal treatment in 7–10 days (if it hasn’t already been carried out).

Open apex

(Permanent teeth)

a) Tooth has been replanted prior to the patient’s arrival

- Clean the gingiva and surrounding area, ensuring there are no lacerations or associated injuries.

- Use clinical and radiographic assessment to ensure the tooth is in the correct position.

- Place a flexible splint which will be in place for two weeks.

- Assess tetanus status.

- Prescribe a course of antibiotics if deemed appropriate.

- Give general trauma advice.

b) Extra-oral dry time <60mins

- Hold the tooth by the crown and gently clean the root surface using saline.

- Use local anaesthetic to provide suitable anaesthesia.

- Gently irrigate the socket.

- Assess for lacerations or loose bone.

- Replant the avulsed tooth gently back into the socket.

- Use clinical and radiographic assessment to ensure the tooth is in the correct position.

- Place a flexible splint which will be in place for two weeks.

- Assess tetanus status.

- Prescribe a course of antibiotics if deemed appropriate.

- Give general trauma advice.

c) Extra oral dry time >60mins

- Clean any soft tissue from the tooth soot using gauze

- Root canal treatment can be carried out at this stage or following re-implantation

- Two per cent sodium fluoride solution can be used to soak the tooth for 20 minutes if you have this available.

- Use local anaesthetic to provide suitable anaesthesia.

- Gently irrigate the socket.

- Assess for lacerations or loose bone

- Replant the avulsed tooth gently back into the socket.

- Use clinical and radiographic assessment to ensure the tooth is in the correct position.

- Place a flexible splint which will be in place for four weeks.

- Assess tetanus status.

- Prescribe a course of antibiotics if deemed appropriate

- Give general trauma advice.

- Start root canal treatment in 7–10 days (if it hasn’t already been carried out).

Summary of key learning points

- Take a thorough history for all paediatric trauma patients taking into consideration; potential head injury, the child’s medical history and tetanus status, the nature of the injury, the time from the trauma to the replantation, whether the tooth has an open or closed apex, the storage medium, the risk of infection, any suspicion of NAI.

- Don’t replant deciduous teeth

- All permanent teeth with a closed apex should have a root canal treatment commenced within 7–10 days (IADT Guidelines)

- Permanent teeth with an open apex which have an extra oral dry time > 60mins should have a root canal treatment commenced within 7–10 days (IADT Guidelines)

- Avulsions with an extra oral dry time of <60 minutes should be splinted for two weeks (IADT Guidelines)

- Avulsions with an extra oral dry time >60 minutes should be splinted for four weeks (IADT Guidelines)

- General trauma advice including oral hygiene, sports avoidance and a soft diet should be given to all paediatric dental trauma patients.

Conclusion

This article has covered the key considerations required for the acute management of a paediatric dental avulsion. Following these steps will allow for the effective, timely management of your patients care, improving the long-term prognosis of the tooth and ensuring no potential child protection concerns are missed.

Authors: F. Capaldi, Paediatric Dental Core Trainee, Glasgow Dental Hospital; C. Park, Consultant in Paediatric Dentistry, Glasgow Dental Hospital

References

- Glendor U. Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries – a 12 year review of the literature. Dent Traumatology 2008:24(6):603-11

- Gutmann JL, Gutmann MS. Cause, incidence and prevention of trauma to teeth. Dent Clin North Am. 1995;39:1-13

- Cortes MI, Marcenes W, Sheiham A. Prevalence and correlates of traumatic injuries to the permanent teeth of school children aged 9-14 years in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Dental Traumatology. 2001;17:22-26.

- Burden DJ. An investigation of the association between overjet size, lip coverage, and traumatic injury to maxillary incisors. Eur J Orthod. 1995;17:513–7.

- Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM. Avulsions. In: Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L, editors. Textbook and color atlas of traumatic injuries to the teeth, 4th edn. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell; 2007. p. 444–88

- Andersson L, Bodin I. Avulsed human teeth replanted within 15 inutes – a long-term clinical follow-up study. Endod Dent Traumatol 1990;6:37–42.

- Andreasen JO, Borum MK, Jacobsen HL, Andreasen FM. Replantation of 400 avulsed permanent incisors. 2. Factors related to pulpal healing. Endod Dent Traumatol 1995;11:59–68.

- Andersson L, Andreasen JO, Geoffery Heithersay et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of traumatic dental injuries. II. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatology 2013. V 3 7 / N O 6 1 5 / 1

- Cairns A, Mok J, Welbury R. Injuries to the head, face, neck and mouth of physically abused children in a community setting. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 2005 vol 15, 5 310 – 318.

- Scottish Government. 2018. GIRFEC information sharing. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.gov.scot/ [Accessed 30 August 2018].

- P. F. Day, T. A. Gregg. Treatment of avulsed permanent teeth in children. British Society of Paediatric Dentistry Guidelines 2005.

- International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 2. Avulsion of permanent teeth Dental Traumatology 2012;28:2 88-96

With the introduction of the first intraoral scanner, CEREC (Chairside Economical Restoration of Esthetic Ceramics) by Dentsply Sirona in 1985, dentistry was offered an exciting alternative to conventional means of impression-taking. Since then, digital technology has developed, resulting in faster, more accurate and smaller scanners than ever before.

As of writing, approximately 15 separate intraoral scanners are available from a variety of companies – all competing within a fierce, growing market. In 2014, the global intraoral scanner market was valued at US$55.3 million, estimated to expand with an annual growth rate of 13.9 per cent from 2015 to 2022 1.

Intraoral scanners have gained traction within the orthodontic speciality, with restorative dentistry following suit. Intraoral scanning technology aims to address fundamentally multiple contemporary clinical issues, including the intuitively error-prone volumetric changes of impression materials and the expansion of dental stone.

This review will provide an overview of the advantages, limitations and clinical applicability of intraoral scanners and serve as an introduction for those unfamiliar with this technology.

Firstly, it is pertinent to discuss the technology of intraoral scanners. The objective of an intraoral scanner is to record precisely the 3D geometry of an object, to allow this to be subsequently used to produce customised dental devices. The fundamentals of intraoral scanning relate to structured light being cast upon an object to be scanned by a handheld device. Images of the object of interest are then captured by image sensors within the handheld scanner and processed by software. This results in the production of a point cloud which is further analysed by software to create a 3D surface model, also known as a mesh 2. The most widely used output file is the STL (stereolithography/standard tessellation language 3).

Numerous technologies exist to process scan data including: triangulation, confocal, active wavefront sampling (AWS) and stereophotogrammetry.

Triangulation works by the concept that the point of a triangle (object of interest) can be calculated knowing the positions and angles of images from two points of view.

Confocal technology relates to the acquisition of focused and defocused images from selected depths – the sharpness of the image infers distance between points and is related to the focal length of the lens 4.

AWS needs a camera and an off-axis aperture module. The module moves around a circular path centred on a point of interest – the distance and depth information are derived from a pattern produced by each point5.

Stereophotogrammetry estimates all co-ordinates through analysing images using an algorithm – relying on passive light projection and software as opposed to active light projection and expensive hardware.

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Enhanced patient comfort | Initial learning curve |

| Gag reflex management | Unable to displace soft tissue – marginal inaccuracies |

| No physical study models requiring storage | Expensive hardware/annual software agreement |

| Streamlined workflow | Unpredictable for extended edentulous sites |

| Predictable for single teeth/implants/short span bridgework (<5 units) | Unable to register dynamic soft tissue relationships |

| Immediate preperation feedback in high magnification (undercut/margin depths) | Requires laboratory familiar with digital technology |

| Improved patient communication |

No matter the imaging processing technology, this data is then constructed into a virtual 3D model. The major challenge of this is rendering a point of interest taken at multiple angles. Accelerometers within the handheld scanner allow distances and angles to be measured between images, with extreme points eliminated statistically, culminating in the production of an STL file suitable for further use to create the custom dental device6.

The accuracy of an intraoral scan is paramount for a well-fitting custom dental prosthetic. This is assessed through the values of “trueness” – being the measured deviation from the actual value and “precision” – the repeatability of multiple measurements.

These terms were defined by the International Organization for Standardization – standard 5725-1. Studies investigating the accuracy of intraoral scanners should ideally include both measurements, to adequately represent both how “correct” a scanner is, as well as how predictably similar its measurements are.

In 2016 8, Ender and co-workers, and other studies, demonstrated intraoral scanner trueness of between 20 m and 48µm and precision between 4µm and 16µm 9-11.

Later, in 2017, Imburgia et al 7 reported scanner trueness and precision in the region of 45µm and 20µm respectively for the most accurate scanners tested. To put these figures into perspective, conventional impression trueness and precision is generally reported in the region of 20µm and 13µm respectively12-14. In its totality, the literature currently reports intraoral scanning is at least as accurate as conventional methods of impression-taking, subject to the complexity of the clinical case 11,15,16.

A common finding is that of partial scans being the most reliable and accurate, when compared to full arch scans2,17,18. When scanning over five units (implants or teeth), the data would suggest scanning is not as predictable as conventional impressions7.

Full arch scans are shown to suffer distortion, specifically at the distal end of the scan 17, 19, 20. Therefore, the scanning of extended preparations or the edentulous mandible is at high risk of error. Shorter scan distances therefore yield the most accurate results9, 21. A clinically acceptable marginal gap for an indirect restoration may be defined at below 100µm22-25.

It is evident that intraoral scanners can achieve errors of consistently less than this value (in single tooth and limited span situations), giving clinical validity.

Advantages

Intraoral scanning provides many advantages for the clinician within single unit, tooth or implant supported restoration or full arch appliance (such as orthodontic retainers or aligners 26-28) situations. Digital records of the patient obviate the need to store plaster models. This has positive implications for storage and consumable costs 27. This data also allows the clinician to easily and accurately monitor changes within the dentition over time – for example, tooth wear or orthodontic relapse 5. It has been evidenced by multiple authors7, 11, 27, 29. that intraoral scanning results in less patient discomfort compared to conventional impressions.

Patients also prefer scanning to conventional methods of impression-taking 28,30 and gag reflexes can be avoided. There is a modest improvement in chairside time 30,31 with a reported average scan time of between four and 15 minutes4, however, greater time saving is gained through the elimination of certain following laboratory steps. A small quadrant scan is ideal for a single restoration 9,32.

Scans of prepared teeth can be scrutinised by the clinician at extreme magnification and software overlays of undercuts/preparation depths are available, with potential for improved clinical outcomes as a result. Files can be directly emailed to the laboratory – thus avoiding the need to physically post an impression. The dental technician can also assess the impression in real time and request another scan to be taken – avoiding an extra visit for the patient 33,34.

Certain problematic sections can be retaken thus avoiding the need to retake a full impression. Patients are shown to feel more involved with treatment and are interested in scanning technology – serving as a good advertising tool35-37.

Limitations

Limitations exist within the practice of intraoral scanning however. As previously mentioned, scanning is currently predictable only within limited parameters. Full arch implant retained prostheses, extended bridgework and complete dentures are currently not supported by compelling evidence. In relation to complete dentures, a predictable dynamic impression of soft tissue borders, muscle attachments and mucosal compressibility is currently severely limited by technology 2.

There is an accepted learning curve in relation to intraoral scanning. It has been reported that subjects with a greater affinity for the world of technology will find the technology easier to adopt than those without this affinity 36,38,39. Issues arise in the detection of deep margins of prepared teeth39 as light cannot record the ‘non visible’ areas of the preparation 2 as normally conventional impression material may be able to displace the gingival margin and record valuable data, following the retraction process. As with conventional impressions, blood or saliva may obscure important margins 40.

With good technique and speed, it has been reported one can overcome many of the reported limitations15,29. The issue of reflective restorations or teeth may also arise. This can result in disruption of the matching of points of interest within the software – resulting in an inaccurate 3D model. This can be counteracted by changing the orientation of the scanner to increase diffuse light, using a camera with a polarizing filter or coating the teeth in powder. Powder coatings (aluminium oxide) can add a variable thickness of up to 90µm41 and further issues arise if taking a full arch scan as powder inevitably gets mixed with saliva – resulting in time spent cleaning teeth and reapplying powder 29.

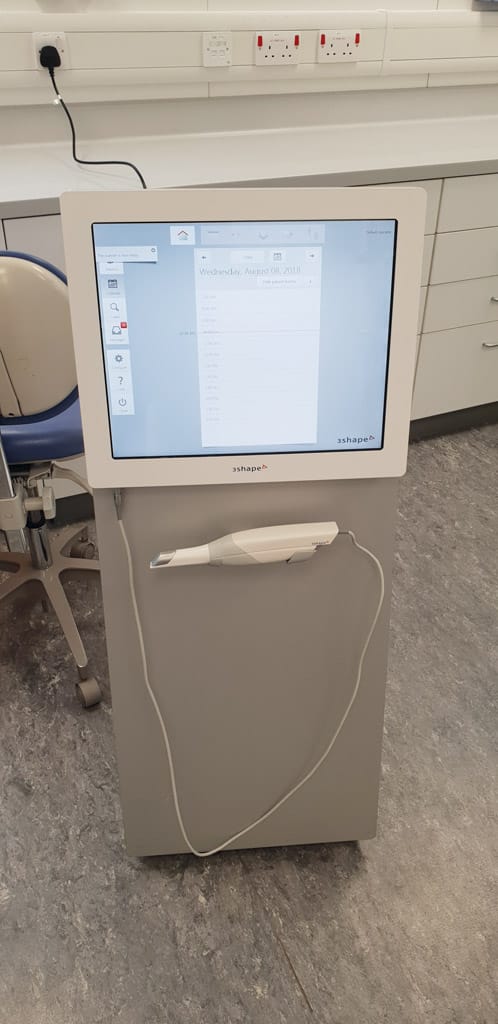

- Figure 1: Mid scan

- Figure 2: Three-shape unit

- Figure 3: Scan of quadrant shown in clinical photo

The scan path can also affect the quality of the scan42 and can result in lost tracking. This should ideally be at a constant distance from the point of interest and moved in a fluid manner, avoiding jerky or fast movements – this can be clinically challenging6. When scanning and tracking is lost, one should return to an area easily recognisable by the software – for example, the occlusal surface of a molar – to predictably re-establish tracking. If scanning a complete arch, multiple small interocclusal records appear to be the most predictable method of achieving accurate articulation or a small scan of the anterior sextants, as described by a 2018 study 32.

The initial expense and management costs of hardware may also be prohibitive – the average intraoral scanner costs between £13,000 and £31,000. An annual update agreement may also exist to “unlock” STL files for use of the laboratory – this again has an associated cost.

As more scanners reach the market, it is likely these costs will become more competitive and attractive to new adopters.

Conclusion

In conclusion, intraoral scanning presents a viable alternative to (and occasionally outperforms) conventional impression techniques within the confines of strict case criteria. Despite being in its late “innovator” and “early adopter phase”, intraoral scanning has shown great potential within restorative dentistry, orthodontics and more recently guided implant surgery (combined with CBCT) 43. Many of its limitations can be circumvented with good clinical technique. Technology, potentially prohibitive costs and market inertia currently prevent its routine use in a wide array of clinical situations.

Author