E-learning in dental vocational training

In brief:

- E-learning could be a valuable tool in Vocational Training if tailored to trainee needs.

- Trainers should have the appropriate support to implement e-learning.

- E-learning technical quality is an important factor in acceptance.

Electronic learning (e-learning) is well established in teaching and learning today. A shift to an online environment has facilitated the notion of ‘anytime, anywhere’ access to educational material. This has become ever more apparent because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The advantages of e-learning have long been recognised within dental education and it has become considered a valuable resource1. From a user point of view, individuals benefit from personalising their learning process to accommodate their preferred study pace and place2.

This act transforms learning from teacher-centred to active learning by the student3. E-learning has also become widely acceptable by graduate professionals to maintain competency in their practice through educational opportunities aimed at continuing professional development 4-6.

E-learning offers the opportunity to balance their learning with personal and work commitments. Despite e-learning becoming embedded in many dental education realms, little is known about the effectiveness of e-learning during dental vocational training. Vocational Dental Practitioners (VDPs – previously known as Dental Vocational Trainees (DVTs or VTs) are a unique type of learner, in that they have the traits of both undergraduate students and graduate professionals, working in a mentored environment under the guidance of an experienced trainer7. Online educational content is available to this cohort of learners. The reliance upon this form of delivery has never been more acute than during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, VT advisers were forced to devise online solutions for delivery of study days and other educational events. These included bespoke packages developed within NHS Education for Scotland, ìoff the shelfî e-learning products from commercial providers and study days delivered by speakers using Teams or GoTo. However, there is no research evaluating its effectiveness during their training, nor evaluating VDPsí opinions towards this method of learning. It was with this in mind that we undertook the present study to gain insight into VDPsí perceptions and experiences of e-learning as a resource in DVT.

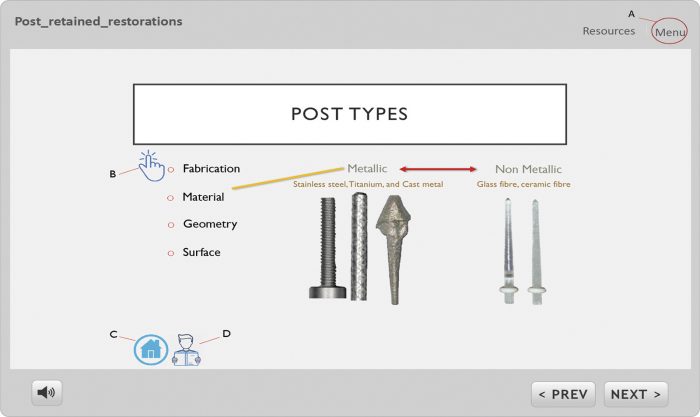

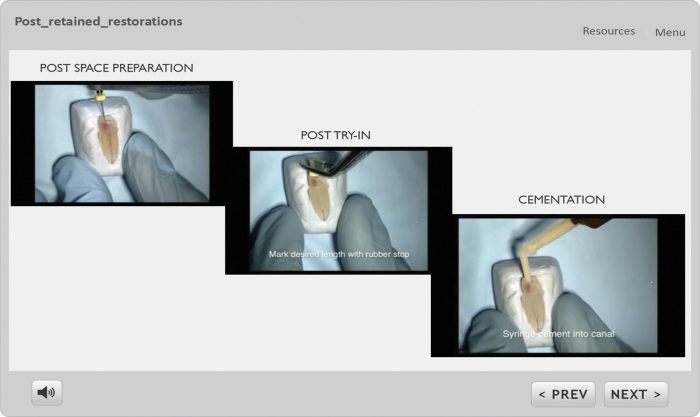

It is without a doubt that usersí acceptance is a major factor for the success of an e-learning educational intervention. We set out to explore the factors important to end users, both VDPs and trainers. To set the scene for our VDPs and their trainers, we developed an online package exploring the provision of post-cores. The intention of the e-learning package was to prepare users to appropriately select cases in need of post-retained restorations and select the necessary treatment strategy. The package included text, images, animation and a series of commentary videos to explore the subject. (Fig. 1 and 2)

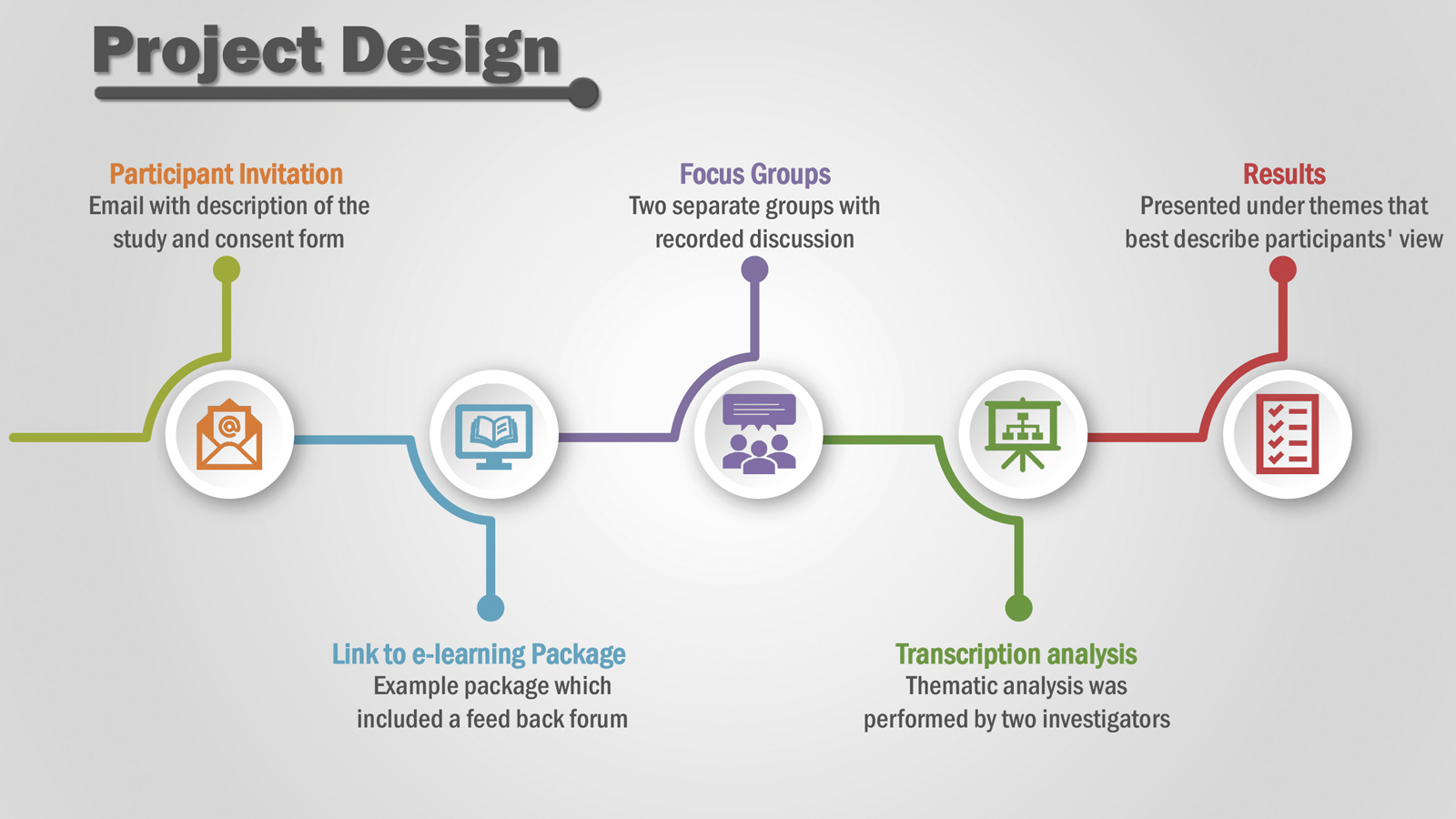

We had asked the VDPs and their trainers to view the package and give their feedback via a questionnaire. We also explored their thoughts on e-learning more generally in focus group sessions. Focus groups can allow an in-depth insight of perspectives on a subject8. We hosted two group sessions (one for VDPs, and the other for trainers) to explore their views of e-learning as an educational intervention in DVT. The group discussions were facilitated using a semi-structured interview guide. The guide addressed usersí previous and current experiences of e-learning; delivery and support; benefits and barriers in implementing e-learning in DVT. Prior to conducting these sessions, appropriate consent was agreed by the participants. Sessions were recorded and independently transcribed. These transcripts were reviewed and coded to identify patterns and themes in the data through a strategy known as a ìgeneral inductive approachî9. This approach involves two investigators independently reading the transcripts multiple times to extract the most relevant themes that describe the transcripts. The investigators then meet and discussed their findings to reach a consensus. (Project design – Fig. 3)

Understanding

The responses to the questionnaire gave insights into the appropriateness of technical elements, usability, and accessibility of the package, many of which were reported favourably. However, it did not provide a measure of whether this is the best method to support VDPs during their training.

A few comments suggested case-based scenarios or ìreal-lifeî patient demonstrations as the preferred method of learning. This is in accordance with growing research suggesting the benefits of this type of learning (i.e., work-based learning or experience-based learning) as an effective gateway to clinical professions 10. It may have been more appropriate to have video content of a patient encounter rather than a simulated post preparation and placement. Such a strategy may improve the perceived relevance to the VDP. Nevertheless, evaluating the technical aspect of an e-learning package is important.

There is a plethora of e-learning interventions and establishing the technical elements that best suit the learner is important. The current evaluation has explored a single intervention in isolation. In accordance with Cookís11 views, future research should be focused on comparing multiple e-learning interventions to each other. This would aid in determining the most appropriate e-learning tools/content for integration into VDP training. But before starting to compare multiple interventions, it is vital to know how best such an intervention would aid in VDP training. This was the rationale for hosting the focus groups. The analysis of group transcriptions provided several themes. The following four themes emerged from the VDP focus group:

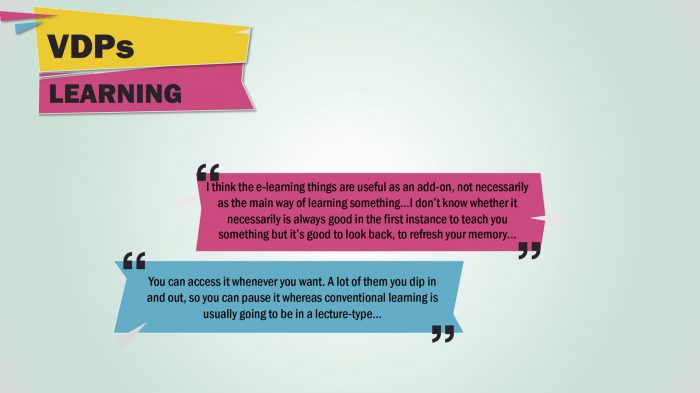

- Supplementing Self-Paced Learning

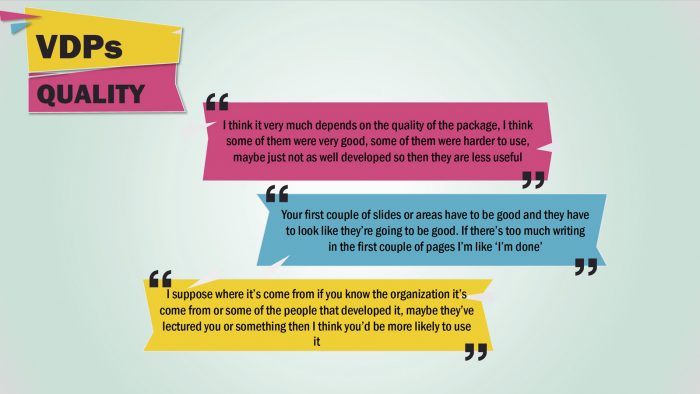

Participants highlighted that e-learning is seen as a supplement to traditional learning methods, in which the individualised self-paced nature of e-learning is valued. (Fig. 4) - Content quality assurance

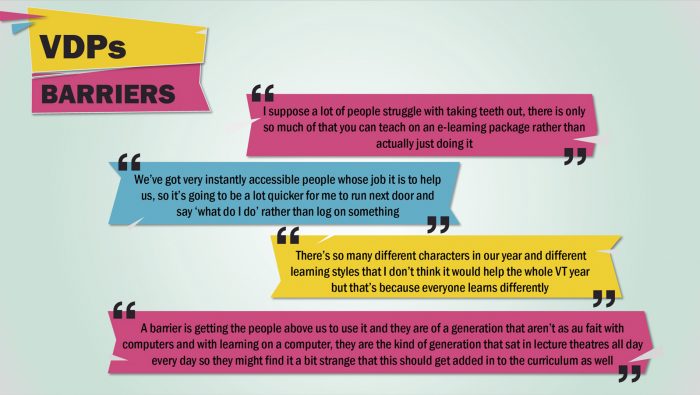

Educational content quality, design and source were factors of importance according to VDPs and were viewed as crucial elements that played a role in the acceptance of an e-learning approach. (Fig. 5) - Barriers to implementing e-learning in DVT

The perceived inability of e-learning approaches in developing clinical skills is seen as an important limitation.

In addition, factors ranging from learnersí learning styles to teachersí teaching approaches were highlighted by participants as factors that could pose potential barriers in developing or implementing e-learning in DVT. (Fig. 6) - Desired e-learning approach

Engaging the end-user, the educational content, and technical design were highlighted as factors to be considered upon implementing an e-learning approach in DVT. (Fig. 7)

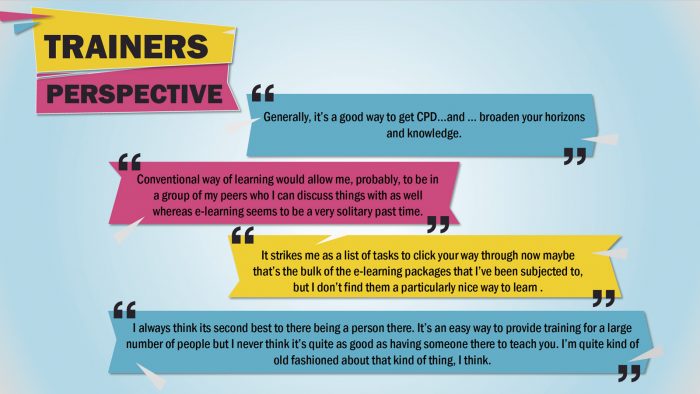

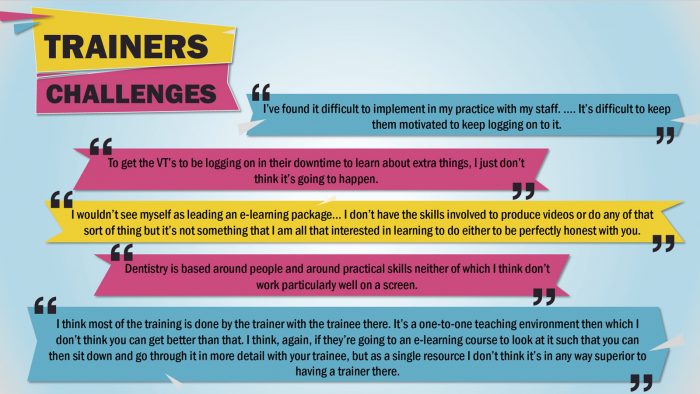

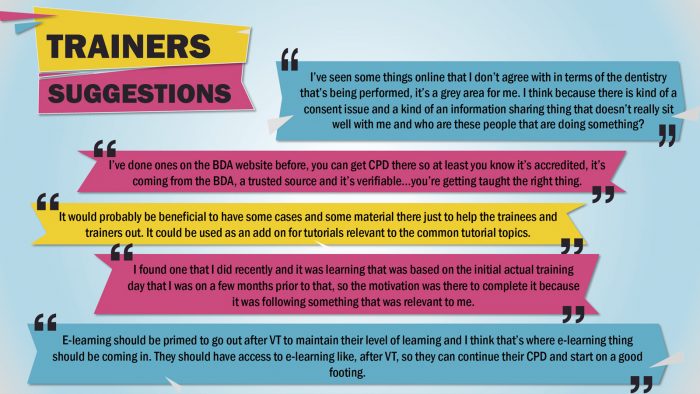

The following three themes emerged from the focus group with trainers:

- Pre-conceived attitudes towards e-learning

Trainers stated the potential of e-learning; however, they had reservations towards this approach in their training. (Fig. 8) - Challenges in adopting e-learning in DVT

Motivation and technical ability were highlighted from a trainer perspective as barriers to employing e-learning in their teaching. (Fig. 9) - Trainers suggestions for e-learning

They highlighted the importance of quality control; educational content; and timing. (Fig. 10)

Focus group discussions showed that VDPs are satisfied with their level of knowledge with regards to theory, and any e-learning intervention would be viewed as a supplement to their training. Several participants questioned how e-learning would help them improve their clinical skills. The VDPs recognised the added value of e-learning in allowing for individualised self-paced learning, but that it does not replace the clinical experience offered by their trainer. This was further expressed in the trainersí comments highlighting their role in providing one-to-one teaching as the main goal of DVT, and to tailor the training to the needs of their VDPs.

Importantly, it was suggested that should e-learning packages be developed it would be important to approach VDPs first to obtain their opinions on what would be required. Both trainers and VDPs stressed the importance of the educational content to be led by VDPs and specific to their needs. This further translates into having topics that help them move into real-life practice environments. Their suggestions were e-learning packages on administrative topics or specific clinical topics that utilise experience-based learning strategies. In addition, technical design was also highlighted as a factor contributing to engagement and acceptability of an e-learning intervention.

Ideas

The suggestions included having a specific short interactive e-learning package with more multimedia and a navigation system.

Both VDPs and trainers state that the essence of DVT is established through the VDP-trainer relationship, with the goal of producing a competent practitioner realised through transfer of experience. Nevertheless, they welcome e-learning as a supplementary resource given that it is supported by their program lead and advisors. This need for quality assurance of the delivered content was highlighted.

In addition, VDPsí opinions showed that they will be more likely to accept and use an e-learning package upon the recommendation of people they trust such as peers or trainers. This could represent a barrier as trainers are currently reluctant to adopt e-learning methodologies in their training.

Adequate

They see that the hands-on training they provide is sufficient for their VDPs, and any more would overload an already demanding training program. Furthermore, while trainers see the potential of e-learning applications, they personally are not fond of this method. It has previously been suggested that a lack of IT skills and, more importantly, difficulty in recognising the pedagogical potential of e-learning are major barriers to trainers/teachers adopting this approach12.

In conclusion, the findings of this study present a first insight into how e-learning is perceived in DVT. As COVID-19 restrictions begin to ease, many advisers are seeking to move back to face-to-face teaching, but it is unlikely that schemes will revert completely to this form. As described in this study it is perceived that e-learning can serve as a supplemental learning tool in DVT despite proving no match for the availability of an experienced trainer.

Trainees and trainers recognise the potential of e-learning if it is customised to the needs of VDPs.

It should be with this in mind that any blended approach is developed for the delivery of DVT.

References

- Rosenberg H, Posluns J, Tenenbaum HC, Tompson B, Locker D. Evaluation of computer-aided learning in orthodontics. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics. 2010 Oct 1;138(4):410-9.

- Al-Jewair TS, Qutub AF, Malkhassian G, Dempster LJ. A systematic review of computer-assisted learning in endodontics education. Journal of Dental Education. 2010 Jun;74(6):601-11.

- Pahinis K, Stokes CW, Walsh TF, Tsitrou E, Cannavina G. A blended learning course taught to different groups of learners in a dental school: follow-up evaluation. Journal of dental education. 2008 Sep 1;72(9):1048-57.

- Sinclair PM, Kable A, Levett-Jones T, Booth D. The effectiveness of Internet-based e-learning on clinician behaviour and patient outcomes: a systematic review. International journal of nursing studies. 2016 May 1;57:70-81.

- Al-Dabaan R, Asimakopoulou K, Newton JT. Effectiveness of a web-based child protection training programme designed for dental practitioners in Saudi Arabia: a pre-and post-test study. European journal of dental education. 2016 Feb;20(1):45-54.

- Welbury RR, Hobson RS, Stephenson JJ, Jepson NJ. Evaluation of a computer-assisted learning programme on the oro-facial signs of child physical abuse (non-accidental injury) by general dental practitioner. British dental journal. 2001 Jun;190(12):668-70.

- NHS Education for Scotland. Dental Vocational (Foundation) Training [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 8]. Available from: nes.scot

- Lingard L. Qualitative research in the RIME community: critical reflections and future directions. Academic Medicine. 2007;82(10):S129-S30.

- Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for qualitative data analysis. 2003.

- Mattheos N, Schoonheim-Klein M, Walmsley AD, Chapple IL. Innovative educational methods and technologies applicable to continuing professional development in periodontology. European Journal of Dental Education. 2010 May;14:43-52.

- Cook DA. The failure of e-learning research to inform educational practice, and what we can do about it. Medical teacher. 2009 Jan 1;31(2):158-62.

- O’neill K, Singh G, O’donoghue J. Implementing eLearning programmes for higher education: A review of the literature. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research. 2004 Jan 1;3(1):313-23.

About the authors

Alqahtani S, McAllan W, Boyle J, Bagg J, McKerlie R and McLean W

Glasgow Dental Hospital & School, University of Glasgow

Corresponding author: Saeed Alqahtani, e-mail: 2195788A@student.gla.ac.uk

Comments are closed here.