The art of dentistry… a search for identity

How creativity could improve wellbeing, clinical practice and public health

Rachel Jackson was six months into a four-year BDS programme at the Aberdeen Institute of Dentistry and, “I thought I was going to walk out the door.”

Partly, at the age of 34, it was “being a student again”. She was also juggling being a mum; away from home during the week, with an overwhelming workload. “I couldn’t find myself, my creativity; I was lost to science. How could I get that back, and manage this volume of information? I had to approach my learning differently. So, I reflected back to my time as a medical illustrator and decided to illustrate what I was learning.”

At school, Rachel’s interest in the convergence of art and the sciences had led her to study Medical Illustration at Glasgow Caledonian University and from there a job at Monklands Hospital; part of a team working with surgeons to depict medical concepts or procedures.

Photography was in her remit, also, for patient information leaflets or publicity pictures. There was a more challenging side to the photography; documenting injuries sustained as the result of serious crimes.

“It was a steep learning curve,” Rachel recalled. “But I had very experienced and supportive colleagues. My approach was to do the job to the best of my ability; it would be disrespectful to the patient if I didn’t do that.”

In her early twenties, now with a baby girl, Rachel decided to move with her partner back to Inverness – “back home” – to be closer to family, and she got a job as a dental nurse. It was part-time and involved patient care in a clinical setting; all things that suited her. By 2013, she had also gained a degree in Oral Health Science from the University of the Highlands and Islands and was working as a therapist in the Public Dental Health Service and independent practice.

“I’m quite a reflective learner,” she said, “constantly wanting to move forward.” Rachel became a part-time tutor, using her photographic skills to teach vocational trainees in clinical photography. This led to a full-time post on the Oral Health Science course from which she had graduated. “I gained so many transferable skills working within an inspirational team using the most up-to-date teaching methods and it was incredibly rewarding seeing new students blossom,” she remembers.

A full-time teaching position became available, but Rachel had a taste for restorative dentistry and opted to develop her clinical skills. As a therapist, she had referrals from 10 to 15 dentists a week. “This was a significant form of peer review and reflective practice. I could learn from patients’ medical conditions, the approaches to treatment planning, what worked and what didn’t,” she said. “I was like a sponge soaking up all this information and quickly outgrew my remit. I was at a crossroads. I enjoy clinical work and contact with the patient. In years to come, I could combine teaching again – but in a different role. So, I thought: ‘Let’s see what happens if I get into Aberdeen [Institute of Dentistry].”

Friends cautioned that she would face hurdles; financially and in balancing family life. She wasn’t quite prepared for the information overload. “The volume of work within a condensed post-graduate BDS course is unbelievable.

“To decide at the age of 34 to turn a stable life upside down to study dentistry, to work, be a mum, and travel – I had to approach my new path a little differently,” said Rachel.

“I had an opportunity; to carve a new identity in dentistry, one that embraced the new but allowed me to keep important elements of who I was before. At the time my priority was to stay connected with my daughter.

“So, I decided to illustrate what I was learning because that’s what I did as a medical illustrator; remove the noise from a procedure so that information could be conveyed concisely. In the process, I could bring these illustrations home to my daughter. I could bridge home and university life, educate my daughter and give her a window on mum’s time at university. It was a vital lifeline for both of us.”

“The volume of work within a condensed post-graduate BDS course is unbelievable. I had to approach my new path a little differently.”

Rachel Jackson

As the course progressed, the number of illustrations began to build. At the end of the second year she took them to Professor John Gibson, the Institute’s director.

“I asked him: ‘What do you think? Is there anything I can do with this?’. I explained that my ability in clinical skills was enhanced by my artwork and vice-versa. It was a bit like going into Dragons’ Den, pitching the idea!

“He listened to my perspective on the profession’s health and wellbeing, teaching methods, my journey in search of an identity and how artwork could be used to connect with patients – just as it had done with my daughter. Professor Gibson took no convincing and has fully supported me ever since in further finding connectedness in the art and science of my chosen profession.”

As well as helping in her learning and improving her mental wellbeing, Rachel began to see the possibilities of dental art in communicating with patients and the public more widely:

“Representing dentistry in a different way, with people being able to see the beauty of the structures and, in turn, value their health more.”

Last November, the British Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry’s annual conference in London hosted an exhibition of Rachel’s work. This spring a permanent installation will be housed at The Campbell Clinic in Nottingham. Rachel is also working on commissions from dentists.

Her next focus is on how the dental curriculum can be enhanced by the arts, whether it’s through using painting to improve fine motor skills or in a wider sense, such as by depicting pain through art to increase empathy with the patient.

There is also a place, she said, for art therapy in dental schools. “For me, the ultimate goal is the acceptance of the arts within dentistry and a shift in the public’s perception of dentistry with creativity – forming a platform to improve the health and wellbeing of the profession as a whole.”

See more at www.medink.co.uk

Majestic structures – ceramic on canvas

From the collection ‘The Beauty Within’, my study of histological sections, patterns and formations seen during tooth development have been transcribed and represented using a medium that I hope captures the essence of a tooth’s inner beauty. I chose to take inspiration from ground sections mainly due to the colours, tones, and textures – reminding me of the gemstone ‘Tiger’s Eye’, used in jewellery. The mesmerising unruly flow of dentine, dammed by a wall of enamel, offers unremarkable beauty. Nature that we respect and very skilfully recreate but, in the process are often reminded of the insubordinate character of the various constituents.

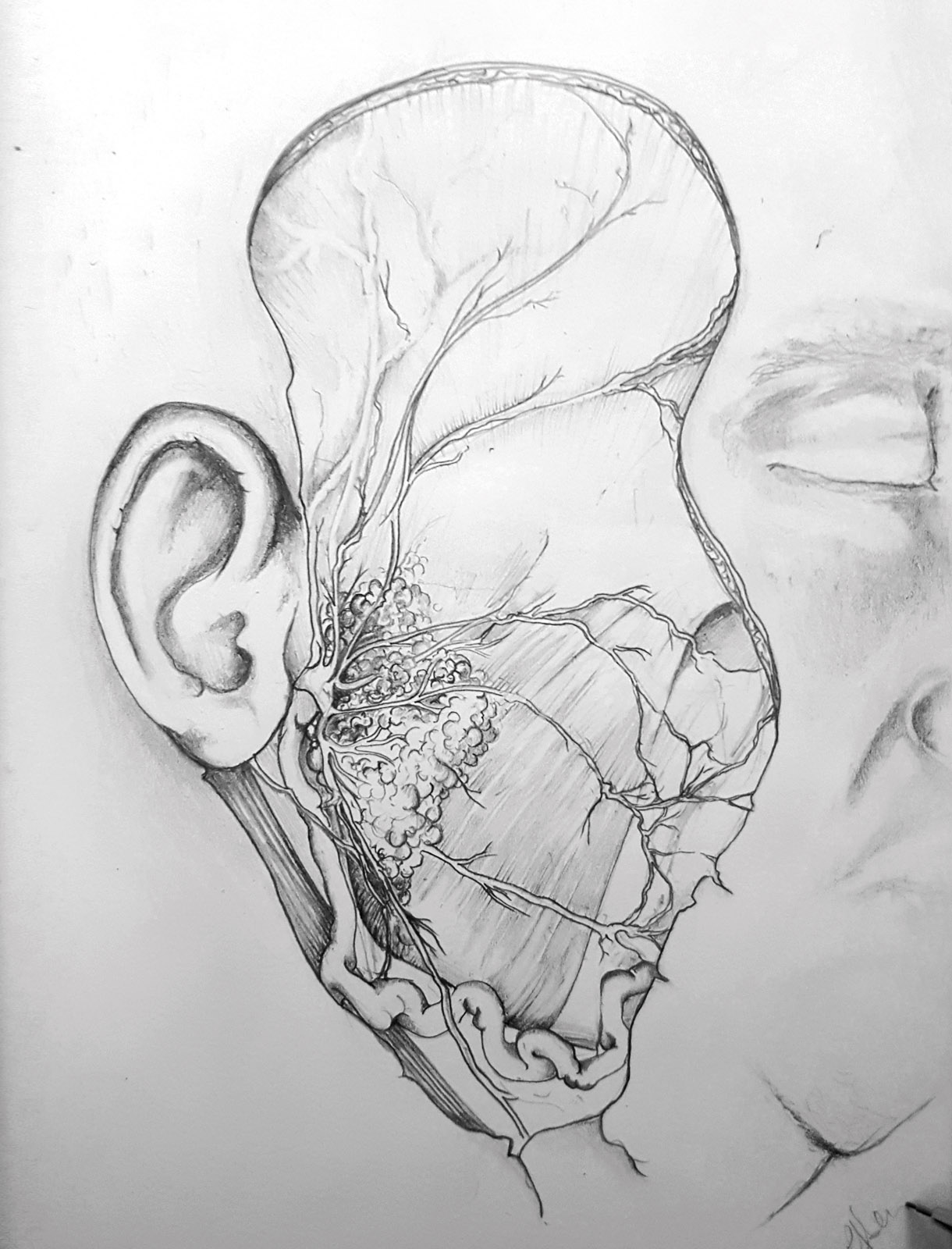

Facial Nerve – pencil on paper

Out of all the cranial nerves, the facial nerve is my favourite; its delicately woven path reminds me of a leaf skeleton. I sketched this specimen as I watched a medical surgeon dissect its path through the parotid gland; considering how best to approach tumour removal. We chatted about what an honour it was to be there, to have these incredible moments and how grateful we both were to those who donate their bodies to education.

In Fashion – mixed media on canvas

Love it or hate it; this painting looks to depict how dentistry is largely represented within today’s society, particularly on social media. Is this today’s definition of beauty? Society appears to say so, particularly the younger generation. Today, an area of dentistry is identified rightly or wrongly with fashionable trends; a luxury buy, a priority before health. It took me quite some time to finish this as it played on my own professional values for some time during the process.

Endo Jelly – pencil on paper

After studying endodontics, I soon realised that treatment was as much about connecting with the tooth itself, visually and using ‘soft skills’, as it was about following a protocol. Endodontics was the first time that I had truly connected the science and art of dentistry. The importance of spatial awareness, tactile senses, and analysis are represented here using the jellyfish – its transparency represents the need to understand morphology, respect canal systems, and connect to the tooth. The jellyfish; enticingly fluid but can yield an unpredictable sting.

Comments are closed here.