Recognition of head and neck skin cancer: A guide for GDPs

P. Steele1, M. Taheny2, D. Boyd3, R. Currie4

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department, University Hospital Crosshouse

1BDS, MBChB, MFDS, MRCS, Senior Clinical Fellow OMFS

2BDS(Hons), MFDS, DCT3, OMFS

3FDSRCPS, FRCS (OMFS), Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon

4FDS, FRCS, FFST (Ed), FRCS (OMFS), Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, Lead Clinician for Skin Cancer, West of Scotland

Introduction

The role of the GDP in the early recognition and management of oral cancer is well recognised and the subject of annual GDC core continuing professional development.

The old adage of a GDP seeing one oral cancer in a practicing lifetime has recently been called into question.

This may now be more accurately reflected as one case per 17 years of practice exposure.

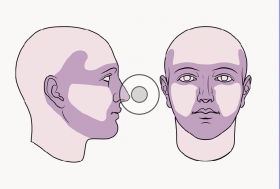

ISD figures suggest 2,000 cases of oral cancer per year, though not all will see a GDP prior to diagnosis. In cutaneous malignancy, ISD figures for 2016 recorded nearly 13,000 cases of melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma (BCC), in Scotland. If this is extrapolated to head and neck presentations, this represents nearly 8,000 patients with cutaneous malignancy potentially presenting to GDPs, allowing for earlier diagnosis and appropriate onward referral.

The head and neck are affected in up to 80 per cent of BCCs, 60 per cent of SCCs and between 22 per cent and 14 per cent of melanomas, the difference being sex dependent.

The aim of this paper is to equip GDPs with the knowledge to facilitate recognition of potential skin cancers and the confidence to make an appropriate onward referral.

Malignant melanoma

Definition

Cutaneous malignant melanoma (MM) is a malignant tumour of neural-crest derived cutaneous melanocytes. Melanomas can arise from a pre-existing pigmented lesion or from previously normal skin. It is both locally destructive, has a propensity to metastasise and is the major cause of skin cancer mortality. Early treatment of the disease is more effective and involves less morbidity. These factors make clinician education, patient education and prevention of the

upmost importance.

Epidemiology

MM is the fifth most common cancer in women and the sixth most common in men in Scotland. There were 1,383 cases registered in Scotland in 2016 with an age-standardised incidence of 26.8 per 100,000 and 162 deaths were attributed to the disease. There has been an increase of the incidence from 2006 to 2016 of 15.2 per cent and a decline in mortality from the disease of 11.5 per cent. In terms of bodily distribution 22 per cent of melanomas present on the head and neck region in men and 14

per cent in females.

Pathology

Melanomas are subdivided into types on the basis of clinical features and pathology.

Superficial spreading malignant melanoma (SMM): This is the most common type of melanoma. Characteristics include an asymmetrical pigmented lesion with irregular borders, irregular pigmentation. Patients may report a growing lesion, a colour change within the lesion, bleeding, crusting

or a change in sensation in relation to the lesion.

Nodular melanoma (NM): This is the second most common type of melanoma. NM can present as a firm papule, nodule or plaque. Approximately 50 per cent have the typical dark pigmentation commonly associated with melanomas. The remaining 50 per cent are hypo/amelanotic and pink-red in colour. The surface of the lesion may be smooth, rough or crusted.

Lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM): The next in terms of frequency is LMM. This commonly presents on the head and neck region of elderly patients. This is the only type of melanoma that is well recognised to develop from a pre-existing lesion that is a form of melanoma in-situ termed lentigo maligna (LM). Classically LM presents as a slow growing tan/brown macule or patch, which progresses on the surface of the epidermis prior to any growth into the deeper layers of the skin. Patients may report a pre-existing pigmented freckle or patch that has changed size, shape or colour.

Desmoplastic type melanoma (DM): This is an uncommon variant of melanoma, accounting for less than 4 per cent of primary cutaneous melanomas. It has a higher tendency for persistent local growth but less frequent nodal metastasis? Clinically DM can be a challenge to recognise as it often presents as amelanotic nodules or plaques, or as ill-defined scar-like lesions. As with LMM it is commonly found in the head and neck region.

Aetiology and risk factors

Solar radiation has been recognised as a cause of melanoma. Exposure to high levels of sunlight in childhood, intermittent unaccustomed exposure and ultraviolet exposure due to sun beds are thought to have a role to play. Other risk factors include a large number of benign naevi and a tendency to freckle (fair-skinned individuals). (Figures 1 and 2)

Clinical Presentation:

Clinical diagnosis of melanoma can be difficult, but they can generally be related to areas of previous sunburn. Any suspicious pigmented lesion should be examined in a good light with or without magnification. As an aid to diagnosis of pigmented lesions, SIGN (1) recommends clinicians should be familiar with the seven-point (2) or ABCDE checklist (3) for assessing lesions and that health professionals should be encouraged to examine patients’ skin during other clinical examinations. A check of the skin of the head and neck region could be incorporated in to a general dental check-up.

Seven-point checklist

Refer people using a suspected-cancer pathway referral (for an appointment within two weeks) for melanoma if they have a suspicious pigmented skin lesion with a weighted seven-point checklist score of three or more.

Weighted seven-point checklist

Major features of the lesions (scoring two points each):

- change in size

- irregular shape

- irregular colour.

Minor features of the lesions (scoring one point each):

- largest diameter 7mm or more

- inflammation

- oozing

- change in sensation.

ABCDE

Asymmetry – the two halves of the area may differ in shape

Border – the edges of the area may be irregular or blurred, and sometimes show notches

Colour – this may be uneven. Different shades of black, brown and pink may be seen

Diameter – most melanomas are at least 6mm in diameter. Report any change in size, shape or diameter to

your doctor

Expert or Enlarging – if in doubt, check it out! If your GP or GDP is concerned about your skin, make sure you see a consultant dermatologist or skin cancer surgeon.

The presence of any major feature in the seven-point checklist, or any of the features in the ABCDE system is an indication for referral. The presence of minor features should increase suspicion, as some melanomas will not demonstrate major features. Any suspicious lesions should be referred to the secondary care, to be assessed by dermatoscopy by a health professional trained in this technique.

Investigations

In order to obtain a diagnosis of melanoma, a tissue sample is required for histopathological examination. A suspected melanoma will be excised in its entirety with a 2mm clinical margin and a cuff of fat. If this is not possible, a punch biopsy or incisional biopsy of the most suspicious area will be performed. Biopsies should not be performed in primary care. When the pathology report is available, the initial staging will dictate whether further investigations are warranted.

Not all patients that develop melanoma require any further investigations other than excisional biopsy. Individuals with melanoma over a certain stage will have directed CT examinations prior to surgery.

Patients over a certain stage may be offered a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). This involves an injection of a radioactive substance and dye, which will highlight the lymph node or nodes to which cancer cells are most likely to spread to from a primary tumour. Once identified, these nodes can be excised utilising a relatively small skin incision to establish if there is in fact cancerous cells that have already metastasised from the primary lesion. SNLB at present is a prognostic tool rather than a technique to improve survival rates.

Treatment

In terms of the primary lesion, surgery is the only curative treatment for melanoma. The histopathological examination of the biopsy will establish the thickness of the melanoma in millimetres, otherwise called the Breslow thickness. This measurement will determine the extent of the lateral margin that is excised around the site of the original skin lesion, this may range from 5mm for in situ disease through to 2cm for thick > 4mm melanomas. This, of course, has to be limited with head and neck anatomy.

Basal cell carcinoma

Definition

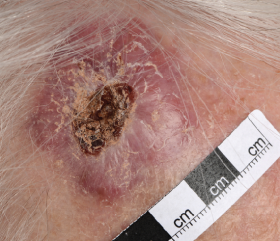

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is a slow growing malignant epidermal skin tumour, which is locally invasive but rarely metastasises. The morbidity associated with BCC is due to tissue invasion and destruction, which can be particularly problematic in the head and neck region when lesions are close to structures such as the eyes and nose. If neglected it can cause extensive damage, require radical treatment and ultimately can be fatal.

Epidemiology

BCC is the most common form of cancer in humans. The incidence increases

with age and the most significant aetiological factors appear to be

genetic predisposition and exposure

to ultraviolet radiation. More than 80 per cent of BCCs occur on the head

and neck. (4)

Pathology

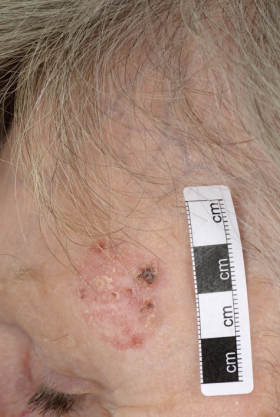

There are a number of clinical variants of basal cell carcinoma with a diverse presentation in terms of clinical appearance and morphology

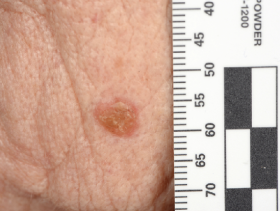

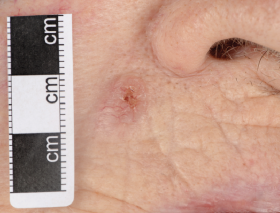

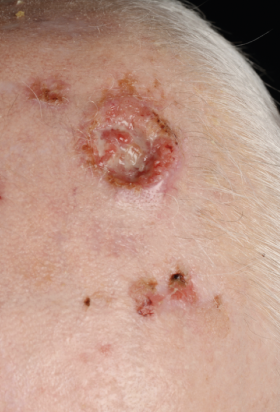

Nodular basal cell carcinoma comprises the majority of cases and predominately occurs on the head and neck region. It presents as an elevated nodule or nodules with a pearly surface with telangiectasia on the surface and periphery. The lesion may ulcerate or have a cystic element.

Superficial basal cell carcinomas present as a thin erythematous plaque. They are scaly and can appear eroded and crusty. A shiny periphery to the lesion can be identified on stretching the surrounding skin.

Morphoeic or sclerosing basal cell carcinoma presents as a yellow-white waxy lesion with poorly defined edges, and the skin involved may be depressed. As with other variants of BCC, it may be associated with localised telangiectasia.(Figures 3-10)

Diagnosis

BCC will be predominately diagnosed clinically. The accuracy of diagnosis can be aided by good light, magnification and dermatoscopy performed by an experienced clinician. If there is any doubt in diagnosis a biopsy can be performed. Imaging techniques such as CT or MRI scanning are reserved for patients in whom there is suspicion the tumour has invaded bone or other anatomically important regions such as the orbit.

Treatment

There are a wide variety of management options for basal cell carcinoma. Treatments can be divided into surgical and non-surgical techniques.

Surgical options

Excision with a predetermined margin involves excision of the BCC with some surrounding normal tissue. Small (<20mm) well-defined lesions excised with a peripheral margin of 4-5mm have a clearance rate of approximately 95 per cent. Larger and less well-defined lesions may require a wider peripheral clearance.

Mohs micrographic surgery involves staged surgical resection of a lesion and examination of the specimen’s margins after each stage to ensure compete excision and extremely high cure rates.

Non-surgical options

Cryotherapy

Liquid nitrogen cryosurgery uses extreme low temperatures to destroy the tumour and surrounding tissue. The disadvantage of non-surgical options is no tissue for histology.

Photodynamic therapy

Photodymanic therapy is used in superficial BCCs where a chemical is activated by light of a pre-determined wavelength leading to local tumour destruction.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy can be used as a primary treatment, but requires patient co-operation and is less frequently used

as a primary modality.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Definition

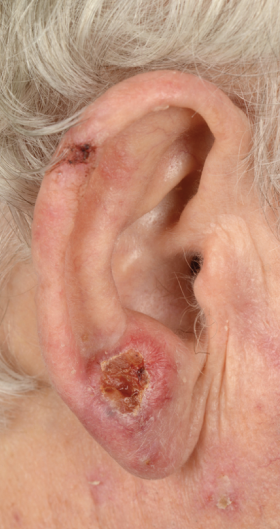

Primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is a malignant tumour, which may arise from keratinising cells of the epidermis or its appendages. It is both locally invasive and has the potential to metastasise to other organs of the body. A commonly cited percentage is 5 per cent of patients go on to develop regional metastasis. Tumour factors such as increased thickness, fat invasion, diameter over 20mm, along with the patient factor of immunosuppression place individual patients in a high-risk category of developing metastasis. High risks clinical sites include the ear and scalp. (5)

Epidemiology

SCC is the second most common skin cancer in the UK and worldwide, with up to 60 per cent involving the head and neck.(4)

About 5 per cent of cSCCs in the UK metastasise, with lesions on the lip most likely to do so. (6)

Clinical presentation

The appearance of SCC is variable. The classic presentation is of an indurated nodular keratinising or crusted tumour with rolled borders that may ulcerate or as an ulcer without evidence of keratinisation. Other non-typical appearances include the growth of a keratin horn or nodule with an intact surface. As such, any new enlarging ulcer, mass, red patch or non-healing lesion on the skin should be treated with suspicion. More than 50 per cent of cSCCs occur on the anterior scalp, forehead and ears, with the lip being another common site.

Although the metastasis rate is low, patients with cSCC can present with regional disease. The parotid region is the most common site followed by the neck. Any head and neck mass should prompt a head and neck skin examination as well as an intra-oral exam. (Figures 11-14)

Diagnosis

As with BCC the initial diagnosis of cSCC can be on a clinical basis or histologically from a biopsy. In the case of rapidly enlarging clinically suspicious lesions, these may be excised with the appropriate surgical margins to avoid any delay in treatment.

Treatment

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. In low-risk, well-defined tumours, a margin of 4mm gives clearance in 95 per cent of cases. High-risk tumours should be excised with a margin of 6mm. (7)

Radiotherapy can be considered in cases where the patient is unwilling or unable to tolerate surgery, and in unresectable cases. (4)

Referral of suspected skin cancers

Dentists can refer suspected skin cancers, such as SCC or malignant melanoma to the patient’s GP or directly to their local oral and maxillofacial surgery department. This should be sent as an urgent referral under the two-week rule. BCCs, unless large or site critical, are usually referred on a routine basis.

Conclusion

Skin cancers are common in Scotland and often present on the head and neck, therefore dentists, who will often see patients more regularly than GPs, are in an ideal position to incorporate screening for suspicious skin lesions into their routine extra-oral examinations. This paper gives an outline of the three main forms of skin cancer, including how to recognise them and how they will be managed in secondary care.

Early recognition and referral of patients with these lesions will lead to improved outcomes.

References

1. SIGN: Cutaneous Melanoma Guideline, March 2017

2. NICE: Suspected Cancer: Recognition and Referral, June 2015

3. ABCD-Easy guide to checking your moles. British Association of Dermatologists

4. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Second Edition, Edited by Cyrus Kerawala and Carried Newlands. Oxford University Press 2014

5. Steel B.J. Skin cancer – an overview for dentists. British Dental Journal May 2014; Vol 216; No 10; 575-581

6. Mourouzis C, Boynton A, Grant J et al. Cutaneous head and neck SCCs and risk of nodal metastasis- UK experience. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2009; 37: 443-447

7. Halpern AC. Hanson LJ. Awareness of, knowledge of, and attitudes to non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) and actinic keratosis (AK) among physicians. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43: 638-642

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the multi-disciplinary skin cancer team at University Hospital Crosshouse, and the support

of Medical Illustration

Comments are closed here.