Material selection

The final part of Steve Bonsor's series of articles examines the factors affecting dental material selection which, he says, is far from Hobson's choice

The first two articles in this series examined how dental materials should be handled prior to and during clinical placement to optimise clinical success. While this is obviously very important, failure to select an appropriate material for the situation will not yield the best clinical outcome. This article addresses the factors which the clinician should be mindful of during this decision making process.

Material selection determined by conservation of tooth tissue

Management of the disease

In modern dentistry there has been a huge change in emphasis with respect to how direct restorative materials are selected. A little over a hundred years ago, in the time of the so-called father of dentistry GV Black, the dentist had a choice of only two materials – namely dental amalgam or gold.

Cavities, therefore, had to be prepared to accommodate the properties of the material. This resulted in sound tooth tissue being needlessly sacrificed so rendering the tooth more prone to fracture and a higher incidence of pulpal death.

The modern philosophy is completely opposite to what it was at the turn of the 20th century. Conservation of tooth tissue is now the most important factor and this has been made possible due to the large increase in the number of materials which are now available. The disease should be manage, i.e. the caries removed, the cavity examined and THEN the appropriate material selected (Fig 1).

At this point, some further preparation may be required to optimise the cavity to conform to the properties of the chosen restorative material. Examples would be the removal of unsupported enamel which may fracture due to its friability or sharp internal line angles which would lead to stress concentrations and a plane for failure (Fig 2).

Influence of dental materials’ properties

It is important that the dentist has a working knowledge of the properties of the various materials which may be used for a given situation as these may have an influence on the selection of the chosen material.

For example, a cavity whose depth is less that 2mm is not indicated for dental amalgam. In this case, it is preferable for an alternative material to be selected such as gold alloy or resin composite so that tooth tissue may be conserved (Fig 3).

In modern dentistry there has been a huge change in emphasis with respect to how direct restorative materials are selected. A little over a hundred years ago, in the time of the so-called father of dentistry GV Black, the dentist had a choice of only two materials - dental amalgam or gold

Steve Bonsor

Material selection determined by clinical situation

Anatomy of the prepared cavity

There are certain prerequisites that may determine the best material for a given situation. For example, resin composite should only be used in cavities which have a complete circumferential enamel margin (Fig 4). This is because the bond gained between enamel and resin composite is the strongest and most durable.

For this reason, the American Dental Association recommends that another material should be selected if a complete enamel margin does not exist 1.

Achievement of an optimal environment for placement

As discussed in the second article, most dental materials are inherently hydrophobic and require a dry environment when they are placed. The inability of the clinician to achieve excellent moisture control when manipulating and using these materials intra-orally will result in inferior results.

Any direct restorative materials containing resin are most susceptible. If the clinician is unable to achieve and maintain adequate moisture control then an alternative, more forgiving material should be considered.

This is also the case for inherently hydrophobic impression materials such as the silicones (Fig 5). In subgingival areas, adequate moisture control may be very difficult to achieve resulting in the margins of the preparation for a cast restoration not being captured accurately, so compromising the rest of the process.

Classically, this is manifested as a rolled edge in the impression (Fig 6). If the clinician cannot achieve excellent moisture control then they may be well advised to choose an alternative product such as a polyether which is more hydrophilic in nature (Fig 7).

Some materials react with moisture. For example, if a zinc containing dental amalgam alloy is contaminated with water, hydrogen gas is evolved which becomes incorporated into the material resulting in its expansion 2. This may have detrimental effects such as extrusion of the material out of the cavity or fracture of the surrounding tooth tissue.

Selecting the appropriate material for mechanical reasons

On occasion, the clinician may be faced with a dilemma of removing more tooth tissue or choosing a material whose mechanical properties are superior. The choice between dental amalgam, gold alloy or resin composite in shallow cavities was discussed earlier. This is also the case for indirect restorations.

If insufficient interocclusal clearance is present, then the clinician may reduce the amount of occlusal reduction done to maintain preparation height and therefore retention for the cast. The use of a non-precious metal alloy in preference to a precious metal alloy will be more successful (Fig 8). Such alloys are stronger, harder and have a reduced ductility than precious metal alloys and may be used in sections of 0.5mm 2. Some of the new zirconium based ceramics may now be used in such thin section as they have sufficiently good mechanical properties to be used in this situation.

Biological considerations

Many dental materials are bioactive (the ability to actively promote activity with the tissues) and need be to biocompatible i.e. the ability to support life and having no toxic or injurious effects on the tissues 2. Inappropriate selection of materials which are cytotoxic will result in detrimental biological effects.

For example, resin modified glass ionomer cement and zinc oxide eugenol cement are contraindicated to be placed directly on pulpal tissue.

The taking and recording of a thorough and comprehensive medical history is an essential prerequisite prior to embarking on any treatment. Hypersensitivity reactions may occur where individuals can become sensitised to certain components in materials. The commonest allergens are methyl methacrylate and hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA).

This latter chemical is cytotoxic and is a powerful dermatological sensitiser 2 3. Patients and dental staff may become sensitised to this substance if it comes into contact with naked skin. Furthermore as surgical gloves are porous and this molecule small, it may permeate the material of the glove so accessing the skin 3 4 (Fig 9).

It is used widely in dentistry in such materials as resin composites, resin modified glass ionomers, compomers and bonding agents to name but a few. Dental staff should therefore be careful when handling these products to avoid hypersensitive reactions. This may be achieved by practising good resin hygiene and by using a no touch technique.

Intermaterial chemical incompatibility

Some materials may interact with each other chemically. There are a number of common examples:

- Zinc oxide eugenol and resin composite. The eugenol acts as a plasticiser (additives that increase the plasticity or fluidity of a material) with the resin resulting in incomplete setting of the composite which will result in inferior mechanical properties and so compromising clinical success (2).

- Self-etch bonding agents may not be used with dual or chemical cured resin composite as they are chemically incompatible. The acidic monomers required for the etching process react with the amine initiator that is needed for the chemical curing mechanism in self- or dual-curing systems (2).

- The catalyst used in silicone impression materials is poisoned by sulphur residues of which are found on latex gloves (2). If the putty presentation of these materials is to be mixed by hand then non latex gloves should be used (Fig 10).

- The astringent Racestyptine (Septodont) and polyether impression materials react chemically resulting in gas being evolved causing porosity in the cast die (2).

The clinician should be mindful of these and other examples and avoid potential chemical reactions when making material selection choices.

Practice management issues

Valid consent

It is important that the advantages and disadvantages of each material are discussed with the patient. This is so that they are involved in the decision and they can make an informed choice as to the care they wish to receive. Sometimes the patient may request the use of a specific type of material at the outset, such as resin composite.

If, at the end of the cavity preparation phase, the clinician feels that the preferred material is not the most appropriate material in the situation then this must be communicated to the patient and the situation discussed. This will involve why this is the case and what the consequences would be if it were to be used.

Furthermore, alternatives should be explained together with their advantages and disadvantages. If there is a deviation from the original agreed treatment plan then an updated one should be issued with it being signed by the patient to confirm their acceptance. At the end of this process, the clinician is safe from a medico-legal perspective with valid consent having been obtained.

Appointment length estimation

Different techniques may result in more time being required to complete the procedure. For example, it has been reported that a posterior resin composite restoration takes three times as long to do as the commensurate amalgam restoration. It is more difficult for the dentist to allocate the correct time to the procedure if there is some uncertainty as to what the final procedure will be.

As mentioned above, a change of material may have increased cost implications as more time may be required to place the restoration.

Surgery set up procedure

The new approach of choosing the dental material to fit the clinical situation is clearly unhelpful for the dental nurse who would prefer to assemble all of the equipment and materials required for the procedure at the beginning of the appointment to facilitate its efficient execution.

They may be well advised to wait until the final decision has been made as to the material selection before getting the chosen materials out of cupboards and drawers.

Conclusions

Each and every dental material has advantages and disadvantages. It is the responsibility of the clinician to carefully consider these together with the intended clinical objectives. Only then can they come to a balanced decision as to the best material to use in the situation which must be underpinned with a thorough knowledge and understanding of all of the materials which are available and their properties. There are so many options that dental material selection is far from Hobson’s choice!

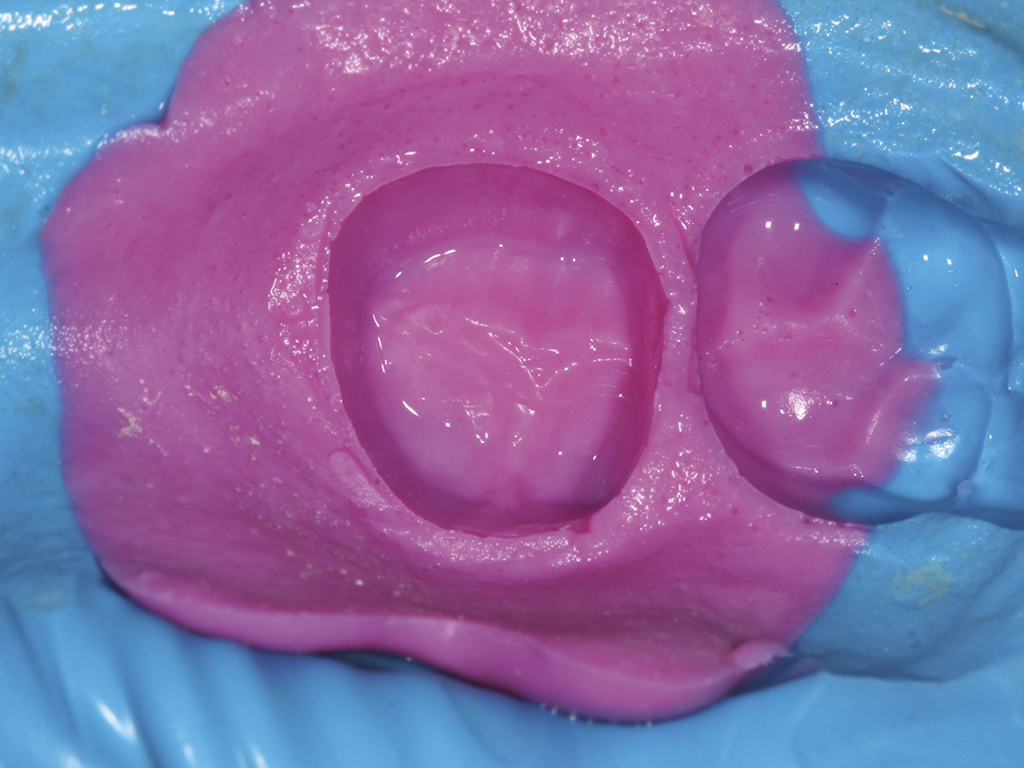

- Figure 1 – Once the caries has been managed then the most appropriate material to restore the cavity should be chosen

- Figure 2 – All unsupported enamel should be removed and a rounded internal cavity form achieved prior to placement of dental amalgam or resin based composite

- Figure 3 – This shallow and unretentive cavity is not suitable for restoration with dental amalgam without further preparation involving the removal of sound tooth tissue. The cavity was restored with resin composite in this example

- Figure 4 – A cavity with a circumferential enamel margin which may be restored with resin- based composite

- Figure 5 – Silicone is frequently used to seal shower units illustrating its inherent hydrophobic nature

- Figure 6 – A rolled edge of a silicone impression indicating moisture contamination during impression taking

- Figure 7 – An example of a polyether impression material which is more hydrophilic than the silicones

- Figure 8 – Using metal on the occlusal surface of a metal-ceramic crown requires less tooth preparation so increasing preparation height and retention. Non-precious metal alloys function in thinner section than precious metal alloys

- Figure 9 – An area of erythema on the dorsal surface of this dentist’s hand caused by HEMA. This occurred by the wiping of instruments contaminated with resin composite on the surgical glove during material placement

- Figure 10 – An additional silicone putty impression material being mixed by hands wearing non-latex gloves

About the author

Steve Bonsor graduated from the University of Edinburgh in 1992 and in 2008 gained an MSc in Postgraduate Dental Studies from the University of Bristol. From 1997 until 2006, Steve was a part-time clinical teacher at Dundee Dental Hospital and School and honorary clinical teacher at the University of Dundee in the sections of operative dentistry, fixed prosthodontics, endodontology and integrated oral care. He currently holds appointments at the University of Edinburgh, as an online tutor on the MSc in Primary Dental Care programme, and at the University of Aberdeen as honorary clinical senior lecturer leading the applied dental materials teaching at Aberdeen Dental School. As well as lecturing throughout the UK, Steve is actively involved in research, having published original research articles in peer-reviewed journals. His main research areas are photo-activated disinfection and the clinical performanceof dental materials.

References

1. Statement on posterior resin-based composites. ADA Council on Scientific Affairs; ADA Council on Dental Benefit Programs. J Am Dent Assoc 1998;129(11):1627-1628.#

2. Bonsor SJ, Pearson GJ. A Clinical Guide to Applied Dental Materials. 1st ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2013.

3. Andreasson H, Boman A, Johnsson S, Karlsson S, Barregard L. On permeability of methyl methacrylate, 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate and triethyleneglycol dimethacrylate through protective gloves in dentistry. Eur J Oral Sci 2003;111(6):529-535.

4. Tinsley D, Chadwick RG. The permeability of dental gloves following exposure to certain dental materials. J Dent 1997;25(1):65-70.

Comments are closed here.