Ensuring an accurate diagnosis

The first part of specialist endodontist Julie Kilgariff’s update on diagnostic terminology in endodontics focuses on pulpal diagnoses

Most routine dental treatment provided to patients is aimed at preventing pulpal and periradicular inflammation and infection. However, it is known that numerous patients seeking emergency dental care have pain of either pulpal and/or periradicular origin 12. Thus it is essential that clinicians are conversant in up-to-date recommended pulpal and periradicular diagnostic terminologies for identifying both healthy and diseased tissues and the associated appropriate management options.

In 2009, The American Association of Endodontists (AAE) 3 released a consensus statement generated from the recommendations of the invitation-only Consensus Conference held in the USA in 2008. This document suggested the adoption of consistent, standardised pulpal and periradicular descriptive terminologies pragmatically based on typical clinical presentations (rather than histological findings).

The aims were to aid accurate endodontic diagnosis and hence treatment, and to enhance communication to patients and colleagues and to heighten understanding of the often degenerative sequence of endodontic disease. Descriptions of the clinical findings for each of the suggested diagnostic terminologies have been produced, however, there is a spectrum of presenting signs and symptoms for odontogenic pain and those patients who fall out with the ‘central tendency’ of the usual clinical presenting features are much more challenging to diagnose.

Clinicians are limited by many of the tests available which often deduce indirect rather than direct information regarding the status of the pulp

Julie Kilgariff

Furthermore, every clinician should be mindful of the dynamic nature of pulpal and periradicular disease which can manifest in both asymptomatic and symptomatic presentations and it is not uncommon for symptomatic conditions to undergo asymptomatic periods and vice versa.

The diagnosis is made following systematic and detailed exploration of the patients’ pain, dental and medical history, clinical and radiological examination, and appropriate special tests and investigations likely to help identify pulpal and periradicular changes. Medico-legal advice 4 recommends documenting details of presenting history, examination, investigations/special tests, diagnoses made and decisions taken/treatment plan made etc. These endorsements are further reinforced within the 2013 guidance from the General Dental Council 5.

It is recommended that a pulpal and periradicular diagnosis should be made for every endodontically involved tooth. This means that, if evidence of a previously pulp-capped, pulpotomised or root-filled tooth is seen, for example on a bitewing radiograph, or a patient gives a history of such treatment, it would be advisable to then examine that tooth clinically for signs and/or symptoms of pulpal and/or periradicular inflammation and infection, and document the results of these findings (both positive and negative) within the patient records.

Depending on the clinical findings related to such a tooth, a periapical radiograph may be considered, particularly if signs or symptoms of possible pulpal and/or periradicular inflammation or infection are identified, or where further restorative intervention is planned for the tooth 6.

The diagnostic terminology presented in this article aims to update clinicians with current terminologies and the most likely clinical scenario encountered with each. Familiarity with this information can facilitate more accurate diagnosis, communication and management of the health or disease of the pulp and /or periradicular tissues. Early diagnosis in endodontics can not only impact favourably on the treatment outcome, but can also involve less expensive, more cost-effective treatment for patients.

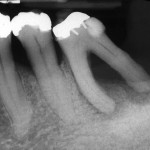

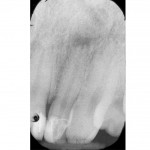

Figures 1a and 1b show an example of a late diagnosis which, if made earlier, may have delayed or prevented the loss of a strategic tooth in an elderly, periodontally compromised patient. Figures 2a and 2b show a tooth with a reduced periodontal support which could potentially have been successfully managed had a horizontal root fracture been identified earlier.

- Figure 1A Tooth 36 was investigated in 2006 because of sporadic low grade symptoms from 36. No pulpal diagnosis was made and no treatment advised/ embarked on. The radiograph shows early signs of a pulpal necrosis most likely because of either the extensive intracoronal restoration present +/- the extent of periodontal disease around the distal root

- Figure 1B In 2009, tooth 36 displayed the features of a pulpal necrosis and chronic periradicular abscess clinically. A further radiograph was taken, a hopeless prognosis advised and the tooth extracted

- Figure 2A Patient attended for a routine review and reported that tooth 22 had become mobile following a traumatic impact. The radiograph was taken and no further tests carried out on the tooth. The diagnosis recorded in the dental records was ‘mobility due to periodontal disease’. The horizontal fracture in the apical third was not identified and no treatment other than non-surgical periodontal care was provided

- Figure 2B The patient returned one year later reporting that the mobility of tooth 22 was becoming problematic and a further radiograph was taken showing external inflammatory root resorption of the horizontal fracture site and periodontal bone loss to the fracture site. A hopeless prognosis was advised and the tooth extracted

- Figure 3 Tooth 22 exhibits evidence of a pulpal necrosis as there is a periradicular radiolucency associated with the periapical area. As this tooth had no clinical signs or symptoms other than discolouration of the clinical crown, a diagnosis of ‘pulpal necrosis and asymptomatic periradicular periodontitis’ was made

Table 1 (below) lists the terminologies suggested by the AAE and it is advised that both a pulpal and periradicular diagnosis is made and documented for each endodontically involved tooth. For example: symptomatic irreversible pulpitis and normal apical tissues.

In formulating an endodontic diagnosis, it is accepted that patient responses to investigations and special tests can be notoriously variable. Clinicians are limited by many of the tests available which often deduce indirect rather than direct information regarding the status of the pulp and/or periradicular tissues 7. Furthermore, no commonly available tests are 100 per cent accurate 100 per cent of the time. And, consequently, the more information clinicians gather regarding the likely status of the pulp and/or periradicular tissues (through using a variety of tests and investigations), the more probable that the diagnosis made will reflect the true status of the pulp and/or periradicular tissues, including identification of when there is no pulpal and/or periradicular disease.

In all cases, it is recommended that a normally funct-ioning tooth with a normal pulp is first tested to generate baseline information against which the test results of potentially problematic teeth can be compared. Discussion of these investigations and tests and their accuracy is outwith the scope of this article and the reader is directed to two excellent papers for more information – Mejàre and colleagues 7 and Pretty and Maupomé 8.

How to identify a clinically healthy/normal pulp

Table 2 illustrates the findings usually associated with a clinically normal pulp. A clinically normal pulp would be expected to respond and function within normal parameters although, histologically, evidence of previous inflammation (fibrosis) may be seen.

Where a tooth is identified, for example on a bitewing radiograph as appearing to have had a previous pulpotomy or pulp cap, further investigation of the pulpal status of that tooth is warranted to confirm whether the tooth is functioning with an apparently clinically normal pulp or not. This is because such teeth are recognised to be susceptible to loosing pulpal vitality in a protracted, asymptomatic fashion that can go undetected9. Diagnosis and treatment of pulpal degeneration at a stage which precedes pulpal necrosis and periradicular changes seen radiographically, is well known to be associated with a more favourable endodontic treatment outcome10.

What are the clinical signs and symptoms of a reversible pulpitis?

Table 3 summarises the clinical signs and symptoms of a reversible pulpitis. In contrast to an irreversible pulpitis, the discomfort experienced from a reversible pulpitis is always caused by a stimulus and never spontaneously occurring.

Dentine sensitivity or hypersensitivity is included under the umbrella of a reversible pulpitis and is an unusual situation in that a chronic pulpal problem can develop and persist although it is not normally associated with degenerating to an irreversible pulpitis.

Reversible pulpitis can be successfully treated by removing any irritant present (such as caries) and protecting exposed dentine (as in the case of a dentine hypersensitivity). This should allow the pulp to return to normal function. However, it is prudent to follow-up and pulp test any teeth which are thought to be at risk of developing an irreversible pulpitis as it is currently impossible to ascertain clinically an individual tooth’s ability to recover from a reversible pulpitis.

The capacity for pulpal recovery will be influenced by previous pulpal insults and inflammation, the degree of pulpal fibrosis and the true histological status of the pulp. Using a minimum of two assessment methods to assess the pulpal status should generate a more reliable assessment of the pulp at the time of symptoms. These can be repeated two to four weeks later for teeth identified as being at risk of undergoing an asymptomatic degeneration of the pulp or an irreversible pulpitis and then necrosis (e.g. heavily restored teeth in older individuals).

What are the clinical signs and symptoms of a symptomatic irreversible pulpitis?

The clinical signs and symptoms demonstrated within this diagnosis are notoriously variable in both intensity of symptoms and the signs/symptoms themselves. Table 4 outlines the varying clinical scenarios which can present to the clinician for this pulpal diagnosis.

Referred, unlocalised pain is regarded as common in symptomatic irreversible pulpitis and so tests which help localise pain can be very useful. For example, selective anaesthesia can aid in localising between mandibular and maxillary pain. Electric pulp testing and other thermal tests can often help highlight the tooth which is the source of the pain.

In contrast to a reversible pulpitis, the discomfort experienced with a symptomatic irreversible pulpitis often arises spontaneously, in the absence of any stimulus and the pain may be worsened by postural changes. Analgesics and systemic antimicrobials are notoriously ineffective in relieving the pain felt with a symptomatic irreversible pulpitis.

What are the clinical signs and symptoms of an asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis?

Teeth which have had pulp caps or pulpotomies performed due to carious pulp exposures are known to be at risk of losing vitality in a slow, asymptomatic fashion because of the extent of the pre-existing inflammation in the pulp at the time of the pulpal exposure. In time, an asymptomatic pulpitis will degenerate further to pulpal necrosis.

Teeth which have a history of what appears to be a symptomatic irreversible pulpitis for which there has been no active treatment, perhaps symptoms spontaneously resolved, are also likely to have either an asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis or pulpal necrosis.

Investigation into the pulpal status of such teeth is advisable. Root canal treatment performed prior to the development of either pulpal necrosis or an identifiable pre-operative radiographic periradicular pathology has a more favourable treatment outcome. It is not unusual for dynamic changes to occur within the root canal system leading to periods of quiescence where symptomatic irreversible pulpitis is asymptomatic.

Older individuals (53 years of age or more) are reportedly at more risk of developing asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis than younger individuals, the latter more frequently presenting with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis. This finding may be because of the reduced innervation of the pulp with ageing and potentially the difficulties that this poses in achieving reliable findings from pulp tests in such teeth9.

Multi-rooted teeth are of note because each canal/pulp may be at a different stage in the degenerative process and thus teeth which are becoming non-vital may still be stimulated to give a positive response to a pulpal test, complicating the diagnostic process.

What are the clinical signs and symptoms of a pulpal necrosis?

Pulpal necrosis is the end result of an irreversible inflammation of the pulp and almost always indicates an infected root canal system is present. This is often evidenced by the development of a periradicular radiolucency seen on a periapical radiograph of the affected tooth +/- the development of other signs and/or symptoms outlined in Figure 3. This is a clear indication to undertake either a root canal treatment or extraction of the tooth in question.

‘Previously Initiated’ and ‘Previously Treated’ pulpal diagnoses

The two remaining pulpal diagnostic terminologies suggested by the AAE are ‘Previously Initiated’ and ‘Previously Treated’. These fairly self-explanatory descriptors allude to either a tooth which has had partial endodontic treatment previously, such as a pulpotomy, pulp cap, pulp extirpation (i.e. ‘Previously Initiated’ endodontic treatment). The latter category describes those teeth which have had a previous root canal treatment completed or surgical endodontics performed (‘Previously Treated’).

Having made a pulpal diagnosis, a periradicular diagnosis can be made and the clinical scenarios and terminology associated with each will be discussed in part two of this article.

About the author

Julie K Kilgariff, BDS MFDS RCS MRD RCS, works as a locum consultant in endodontics at Glasgow Dental Hospital and as a specialist in endodontics at Blackhills Specialist Dental Referral Clinic, Aberuthven.

References

- Dailey YM, Martin MV. Are antibiotics being used appropriately for emergency dental treatment? British Dental Journal. 2001; 191(7): 391-3

- Tulip DE, Palmer NO. A retrospective investigation of the clinical management of patients attending an out of hours dental clinic in Merseyside under the new NHS dental contract. British Dental Journal. 2008; 205(12): 659-64

- The American Association of Endodontists. Consensus Conference Recommended Diagnostic Terminology. aaeconsensusconferencerecommendeddiagnosticterminology.pdf (Accessed 22 January 2015)

- The Medical and Dental Defence Union of Scotland. Essential Guide to Medical & Dental Records. essential guide to medical and dental records12-09.pdf (Accessed 22 January 2015)

- General Dental Council. Standards for the Dental Team. Standards for the Dental Team.pdf (Accessed 22 January 2015)

- European Commission. Radiation Protection 136. European Guidelines on Radiation Protection in Dental Radiology. Luxembourg Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2004

- Mejàre IA, Axelsson S, Davidson T, Frisk F, Hakeberg M, Kvist T, Norlund A, Petersson A, Portenier I, Sandberg H, Tranaeus S, Bergenholtz G. Diagnosis of the condition of the dental pulp: a systematic review. International Endodontic Journal. 2012; 45(7): 597-613

- Pretty IA, Maupomé G. A closer look at diagnosis in clinical dental practice: part 1. Reliability, validity, specificity and sensitivity of diagnostic procedures. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 2004; 70(4): 251-5

- Michaelson PL, Holland GR. Is pulpitis painful? International Endodontic Journal. 2002; 35(10): 829-32

- Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K. A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment: part 1: periapical health. International Endodontic Journal. 2011; 44(7): 583-609

Table 1

AAE Pulpal & Periradicular Diagnostic Terminologies| AAE Pulpal and Periradicular* Diagnostic Terminologies | |

|---|---|

| Pulpal Diagnoses | Normal Pulp Reversible Pulpitis Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis Asymptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis Pulpal Necrosis Previously Initiated Therapy Previously Treated |

| Periradicular Diagnoses | Normal Periradicular Tissues Symptomatic Periradicular Periodontitis Asymptomatic Periradicular Periodontitis Acute Periradicular Abscess Chronic Periradicular Abscess Condensing Osteitis |

Table 2

Identifying a Clinically Healthy/Normal pulp| Describes a pulp with no clinical signs or symptoms to suggest any form of disease occurring |

|

|---|---|

| Patient history | Nil |

| Clinical findings | No findings of note |

| Pulp tests | Reacts to cold stimuli with mild discomfort lasting for no more than one to two seconds after the stimulus is removed. Electric pulp testing does not generate an exaggerated response, any discomfort resolves seconds after removing the stimulus |

| Periradicular tests: | |

| Percussion | Negative |

| Palpation | Negative |

| Swelling/sinus | None |

| Radiographic findings | An intact lamina dura around the full length of the root and a normal periodontal ligament space seen |

Table 3

The Clinical Signs and Symptoms of a Reversible Pulpitis| Describes a mild pulpal inflammation which is capable of resolving/ healing and returning to normal if appropriately managed |

|

|---|---|

| Patient history | Sharp pain to stimuli which can be thermal &/or mechanical &/or osmotic changes |

| Pain is NOT spontaneous | |

| Clinical findings | +/- caries +/- fracture of tooth/restoration +/- defective/new restorations +/- recent periodontal debridement +/- tooth surface loss +/- exposed dentine |

| Pulp tests | Exaggerated reaction to cold stimuli & discomfort ceases within a few seconds or immediately when the stimulus/sensibility test removed +/- an exaggerated but short lasting discomfort to electric pulp testing |

| Periradicular tests: | |

| Percussion | Negative |

| Palpation | Negative |

| Radiographic findings | Many of the relevant clinical findings described above may be evidenced radiographically NO radiographic changes seen periradicularly, normal periradicular tissues present |

Table 4

The Clinical Signs and Symptoms of a Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis| Describes a painful, severe pulpal inflammation which is a degenerative process from which the pulp cannot heal |

|

|---|---|

| Patient history | Dull ache or throbbing severe pain +/- sleep disturbance /worse lying down Spontaneous pain lasting minutes or hours Pain may be constant or sporadic Can be hard to localize source of pain & can present as referred/radiating pain Often intense discomfort to temperature changes from foodstuff/beverages |

| Clinical findings | +/- deep caries +/- defective or new extensive restorations Often a heavily restored tooth |

| Pulp tests | Exaggerated reaction to cold, hot & electric pulp stimuli & discomfort lingers for 30 seconds or more after stimuli removed. Mild stimuli can cause extreme reaction, e.g. with heat tests |

| Periradicular tests: | |

| Percussion | Negative until periradicular tissues affected, then positive |

| Palpation | Negative but as periradicular tissues become affected, becomes positive |

| Swelling/sinus | None |

| Radiographic findings | A ‘widened’ periodontal ligament space may be seen No frank periradicular changes are seen on conventional radiographs until pulp is necrotic In cases where the source is difficult to identify, radiographic findings may suggest likely teeth: e.g. deep caries, deep restoration, dentine pins retaining a restoration |

Comments are closed here.