Pioneering dental education

A short history of the Royal Odonto-Chirurgical Society of Scotland, 1867-2017

The Odonto-Chirurgical Society of Scotland, founded in 1867 is the oldest dental society in the United Kingdom, if not in the world, still actively functioning under its original title and upholding the original objectives. This year it celebrated its 150th anniversary.

Its roots are traceable to January 1865, when John Smith invited a few surgeons to meet in the Edinburgh Dental Dispensary, with the purpose of founding a society of persons practising ethical dentistry.

Smith was a man with foresight and concern for the welfare of his fellows. Born in 1825, son of a surgeon who practised dentistry, he qualified in surgery in 1847. On the death of his father in 1851 he carried on the dental practice at 12 Dundas Street, Edinburgh.

dentistry at that period was unscientific. the majority of those who practised were charlatans, many being illiterate

Dr Paul R Geissler

In the 1840s and 1850s the dental state of the population of the city was very poor. Concerned about this, in 1865 Smith had instituted a course of clinical instruction in dentistry at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, the first person in Scotland to do so.

Then in 1860, along with his friends Francis B Imlach, Peter Orphoot and Robert Nasmyth, Smith founded the Edinburgh Dental Dispensary, later to become the Edinburgh Dental Hospital and School, to provide clinical instruction for student dentists and also to provide dental care for the poorer citizens of Edinburgh.

At the meeting in January 1865, those present were David Hepburn, Nasmyth, Orphoot, Andrew Swanson, Matthew Watt and John Wright. It was Smith who suggested the title ‘Odonto-Chirurgical Society of Scotland’ and submitted a code of rules which he had drafted.

However, there were differences of opinion about whether membership should be restricted to those with a surgical qualification. This could not be resolved and, after two meetings, the idea was abandoned. Hepburn, however, was convinced of the ultimate success of the proposal.

To understand the problems in founding such a society, one has to realise the state of dentistry at that time. To very few did it appeal as a profession. Dentistry at that period was unscientific and crude and training was, at best, by apprenticeship. The majority of those who practised dentistry were charlatans, many being illiterate.

Dentists in 1860s still adhered to the policy of total isolation. It was almost the exception for a practitioner to know a fellow practitioner. If he did, he was careful never to divulge anything connected with his own practice. All such knowledge was guarded as state secrets in a way that cannot be appreciated today.

The struggle for financial survival for some surgeon-dentists was extremely difficult. Some were forced by necessity to be slightly elastic with their ethics. It was this elasticity of ethics which enabled the charlatans to gain some elementary instruction in dentistry. These skills they then developed by trial and error. The claims which such persons made and the fees they charged were often outrageous. They concentrated almost exclusively on the extraction of every tooth (sound and unsound) and the insertion of artificial dentures. These services were expensive, unhygienic and largely unsatisfactory. This state of affairs was totally inadequate.

For the man in the street in the 1860s, there was no way to recognise the ethical dentist from the unethical or even the charlatan. A revolution in the education and training of dentists and in the regulation of dentistry was needed. However, the first Dentists Act was not to be enacted until 1878 and the British Dental Association was not incorporated until 1880.

It required some notable person or persons to give the impetus. Smith had been one such person, Hepburn was another.

An initial breakthrough had occurred in England in 1860. The Royal College of Surgeons of England had introduced the Licentiate in Dental Surgery (LDS) diploma and the first graduation had occurred on

13 March of that year.

The practice of the surgeon-dentists having a dinner on 13 March, the anniversary of the introduction of the LDS diploma in 1860 had lapsed in London by 1867, but was continued in Scotland. Hepburn utilised the occasion by inviting the surgeon-dentists practising in Scotland to meet on the 13th, prior to the dinner of Licentiates in Dental Surgery in the Douglas Hotel, in Edinburgh’s St Andrew Square.

On his suggestion it was decided to found the Odonto-Chirurgical Society of Scotland and to adopt the laws and constitution, with some alterations which Smith had drafted two years earlier and were identical in principle to those of the Odontological Society of Great Britain.

Law 111 of the Odonto-Chirurgical Society adopted at that meeting represented an enormous ethical advance. It stated: “No member shall; be permitted to advertise in the public journals his profession, his mode of practice, or his charges. They state not be permitted to expose specimens of their work for public inspection, nor to carry on their practice in connection with any other business, nor to hold any patent relating to dental practice, nor to conduct themselves in any way, which the Society may consider derogatory to the profession.” Expulsion was the penalty for infringement.

The founding of the Odonto-Chirurgical Society proved a great stimulus to the ethical and scientific progress of the profession in Scotland, which up to then had been in chaos, particularly so at a time when there was no dental society nearer than London, so that to attend meetings entailed expensive and long journeys.

Nasmyth was elected first president, Hepburn the first treasurer and John Cunningham the first secretary. Interestingly, Smith did not become a member until somewhat later. He was president from 1881 to 1883 and was later to be president of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh from 1884 to

85, and the fourth president of the BDA in 1884.

- The original seal of the society, dating from 1867

- John Smith, MD (1847) FRCSEd (1861) LLD (1884), president of the society from 1881 to 1883

- David Hepburn, LDSRCS Eng (1860), president 1877-1879

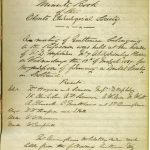

- Initial page of the original handwritten constitution of the society

- William Bowman MacLeod, LDSRCSEd (1879) FRSE, president 1885-1887

Membership of the emerging society stood for some years at 13. However, in 1879, with the introduction of the LDS diplomas from both the Edinburgh and Glasgow Colleges, there was an increase in applications for membership as these persons with their approved training were considered to be ethical dentists and therefore eligible to join this august body.

Originally, meetings were held quarterly, alternately in Edinburgh and Glasgow, later restricted to three, two in Edinburgh and one in Glasgow. Since 1887, all the ordinary meetings have taken place in Edinburgh on the second Thursdays of November, December, January and February, with the Annual General Meeting in March, and the Annual Dinner on the Friday nearest 13 March.

From 1867 to 1869, the society met in Edinburgh in the home of the secretary David Hepburn at 5 Abercromby Place. From 1870 to 1879 the meetings were held in the rooms of the Obstetrical Society at

5 St Andrew Square. Thereafter it met in the Dental Hospital and School, first at 30 Chambers Street then 5 Lauriston Lane and, from 1894, 31 Chambers Street. It was only in 1949 that the society met in

the Royal College of Surgeons.

The titles of some of the early papers delivered to the society should be mentioned. In March 1868, William Williamson of Aberdeen delivered the first paper to the society, entitled Some of the Causes of Failure of Stoppings, which created a very animated discussion in which all the gentlemen present took part. It should be realised that, at that time, tooth preparation could only be accomplished with hand rotated instruments, chisels or excavators. The foot drill did not appear on the market until 1871. Silicate cement and amalgam were used but the latter was very unstable.

Charles Fox of London read a paper on Nitrous oxide, its preparation and use. Among some of the subjects covered in the early years were Filling teeth with Gold, Amalgam fillings and William Bowman MacLeod reported on Tooth wear in Bagpipe Players, which induced a great deal of discussion. There was also an intriguing paper entitled Oesophagotomy and Gastronomy for recovery of a Denture impacted in the Oesophagus, but no report on the outcome for the patient.

The society has survived and prospered over the years. It has seen the developments of dentistry through greatly enhanced educational and scientific developments, and the coming of the National Health Service, each of which have benefited our patients. It has come through two world conflicts.

Our founding fathers strove to achieve high standards and, over the last 150 years, the society has strived to uphold these standards. This was recognised by the granting of a Royal Charter in 1967, it becoming the Royal Odonto-Chirurgical Society of Scotland.

Professional standards

When the Odonto-Chirurgical Society of Scotland was founded in 1867, the committee were determined that members should adhere to the highest standards, in ethics and probity as evidenced in the constitution.

Some comments on the constitution as originally drafted:

Obligations of members

“No member shall be permitted to advertise in public journals his profession, his mode of practice, or his charges. They shall not be permitted to expose specimens of their work for public inspection, nor to carry on their practice in connection with any other business, nor hold any patent relating to dental practice, nor to conduct themselves in any way which the society may consider derogatory to the profession as long as they continue as Members of the Society.”

Constitution 1867, Page 4

Advertising

“No member shall be permitted to advertise in public journals his profession, his mode

of practice, or his charges.”

Today this hardly applies.

Business organisation

“…nor to carry on their practice in connection with any other business.”

This has fallen into abeyance.

Holding dental patents

Legally permitted but possibly unacceptable on ethical grounds.

Conduct

“…nor to conduct themselves in any way which the Society may consider derogatory to the profession as long as they continue Members of the Society.”

This section still applies.

Standard of dress

In 1988, the society was again concerned about the maintenance standards:

“It was agreed that members should be encouraged tactfully to maintain the standard of dress at a professional level.”

Minute of 7 Jan 1988

Since that time clinical changes have occurred. Modern practice frequently involves changing from day wear into clinical garb. Thus the agreed comment of 1988 probably has little meaning today.

About the author

Dr Paul R Geissler is the honorary curator of the

Menzies-Campbell Collection at the Surgeons’ Hall Museum, Edinburgh, and the author of The Royal Odonto-Chirurgical Society of Scotland 1867-2017, 150 Years of Progress

Comments are closed here.