The coronectomy technique

The coronectomy technique Oral Surgery

Impacted lower third molars are a common developmental anomaly in primary care that requires an evidence-based approach to gain informed consent from patients in treatment planning. The prophylactic removal of third molars has been discouraged since the development of SIGN 43 and NICE guidelines.

The SIGN guidance suggests “surgical procedures for extraction of unerupted third molar teeth are associated with significant morbidity including pain and swelling, together with the possibility of temporary or permanent nerve damage, resulting in altered sensation of lip or tongue” 1.

The introduction of SIGN guidance initially showed a reduction in the number of cases of third molar removal in primary care. However, since 2005 there has been a steady upward trend 2. McCardle and Renton suggest this initial change resulted in patients retaining third molar teeth due to rigid interpretation of the guidance. The extraction of third molars may have been delayed due to the use of antibiotics to manage pericoronitis or a more palliative approach to clinical decision-making. As patients retain third molars into later life they are more vulnerable to caries and pathology, particularly where the teeth are impacted leading to the ‘rebound’ in data.

Inferior alveolar nerve injury is a significant complication associated with the removal of third molars and is reported to occur in up to 3.6 per cent of cases permanently and 8 per cent of cases permanently 3. Such injuries can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life and should be taken into consideration when making clinical decisions and gaining informed consent. The coronectomy technique is an alternative procedure to complete removal of a third molar in high-risk cases and can reduce the risks of nerve damage.

- FIGURE 1 – Example of low-risk case where tooth 48 is mesially impacted but not closely associated with the inferior dental canal. Note the presence of distal caries on tooth 47

- FIGURE 2 – Example of a moderate-risk case of horizontal impactions of 38 and 48

- FIGURE 3 – Example of a high-risk case where both 38 and 48 are closely associated with the inferior dental canal

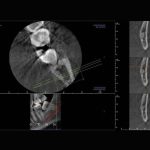

- FIGURE 4 – CBCT imaging demonstrating a close relationship between the IAN and a mesially impacted 38

- FIGURE 5 – Roots remaining in situ after removal of crown

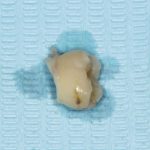

- FIGURE 6 – Crown sectioned below the ACJ and removed

- FIGURE 7 – Left OPT demonstrating post-op view of retained roots in situ

Assessment of lower third molars

A methodical approach to the gathering of relevant information from the clinical history is key to successful management. The guidance provided by SDCEP document ‘Oral Health Assessment and Review’ provides a comprehensive overview to history taking 4.

The patient’s history should be combined with a thorough clinical and radiographic examination. Practitioners are advised to follow IRMER 2000 5 in ensuring any exposure is justified, optimised and dose limited. Colleagues are also referred to FGDP’s ‘Selection Criteria for Dental Radiography’ 6 for guidance in their decision making process.

The guidance indicates that radiographs are indicated in the “extraction of teeth or roots that are impacted, buried or likely to have a close relationship to important anatomical structures. With the exception of third molars, the appropriate radiograph will normally be a periapical view”. As a result, an OPT is generally the radiograph of choice for assessment.

All images should be reported on by the practitioner and particular attention paid to the following radiographic signs that could result in a higher risk of inferior alveolar nerve damage as described by Palma-Carrió et al 7:

- Darkening of the root

- Deflection of the root

- Narrowing of the root

- Bifid root apex

- Diversion of the canal

- Narrowing of the canal

- Interruption in white line of canal.

Colleagues are advised to make an assessment of the difficulty of the case and their own surgical skills before considering the options of surgery in primary care, referral to a dentist with a special interest in oral surgery or referral to secondary care. Some radiographic examples are shown in Figs 1-3.

CBCT

In high-risk cases, the European Commission Cone Beam CT for Dental and Maxillofacial Radiology 8 guidance states: “Where conventional radiographs suggest a direct inter-relationship between a mandibular third molar and the mandibular canal, and where a decision to perform surgical removal has been made, CBCT may be indicated.”

Matzen et al carried out a study of 186 lower third molars that were assessed using both panoramic imaging and CBCT to decide whether surgical removal or coronectomy was indicated 9. Treatment planning was carried out after the initial two-dimensional imaging followed by a second treatment plan after three-dimensional imaging. The authors found that the treatment plan was changed for 22 teeth and thus CBCT influenced the decision making process in 12 per cent of cases. The authors advised that “narrowing of the canal lumen and canals positioned in a bending groove or in the root complex observed in CBCT images were a significant factor for deciding on coronectomy”.

The example in Figure 4 demonstrates a case of a mesially impacted tooth 38 that required CBCT investigation as part of the examination and consent process. CBCT demonstrated a close relationship between the roots of 38 and the IDN. In this case, the patient was offered the opportunity of both surgical removal and coronectomy. Given the potential for altered sensation or numbness, the patient opted to undergo a coronectomy.

Given the significant impact of CBCT imaging in treatment planning it is essential that patients in high-risk cases are offered three dimensional imaging and coronectomy where appropriate in order to gain informed consent.

Evaluation of findings and consent

On reviewing the findings of both clinical and radiographic assessment, clinicians should refer to the guidance available in the UK in deciding whether surgery is indicated 1,10,11:

- One or more episodes of pericoronitis

- Caries in the third molar or lower second molar. The future risk of caries in the second molar should be taken into account

- Pulpal/periapical pathology

- Periodontal disease

- Internal/external resorption of the tooth or adjacent teeth

- Follicle disease including dentigerous cysts

- Prophylactic removal in specific medical conditions such as before chemotherapy/radiotherapy

- To facilitate effective restorative treatment including prosthesis

- Patients whose lifestyle precludes ready access to

dental care.

This list is not exhaustive and practitioners are advised to make an individualised risk assessment and assist patients in making informed decisions in relation to their ongoing care.

Consent

Informed consent is an essential part of the assessment process and it is advisable to obtain written consent.

Patients should be alerted to the following risks:

- Pain and discomfort

- Swelling and trismus

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Localised alveolar osteitis or infection (around 20 per cent of cases)2

- OAF/OAC in the case of upper third molars

- Paraesthesia or anaesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve or lingual nerve in lower third molars (8 per cent temporarily and up to 3.6 per cent of cases permanently) 3.

In high-risk cases, patients should be offered the opportunity of a coronectomy procedure where appropriate. Patients should be aware of the possible need for a second surgical procedure at a later date and the possibility that, should the roots become mobile, the need for complete extraction 12.

Patients should be given adequate time to consider the risks involved and an opportunity to have their queries answered, this may involve a second visit to allow sufficient time.

Procedure

The coronectomy technique or “deliberate vital root retention” is a means of removing the crown of the tooth but leaving roots intimately related to the inferior alveolar nerve untouched in order to reduce the risk of nerve damage. The procedure is carried out as follows 13:

IDB and long buccal infiltration anaesthesia are provided. The author’s preference is lidocaine 2 per cent, 1:80000 adrenaline, as an IDB and articaine 4 per cent, 1:100000 adrenaline, given as a buccal infiltration.

A full thickness mucoperiosteal flap is raised to obtain sufficient access and expose the third molar tooth.

A fissure bur is used to remove buccal bone and expose the crown of the tooth down to the ACJ. The fissure bur is used to drill into the pulp at the mid centre of the buccal grove as it intersects with the ACJ. This cut is lateralised to create space for an elevator. The cut should be no more than the length of the bur in order to avoid perforation of the lingual cortical plate.

An elevator, such as a Coupland’s or straight Warwick James, is used to fracture the crown from the roots. It is essential to take care and not apply too much pressure at this stage to prevent mobilisation of the roots. If mobilisation occurs, the roots must be elevated and removed.

A rosehead bur can then be used to remove any spurs of enamel and to reduce the roots a few millimeters below the alveolar bone crest.

The pulp chamber is left untouched and primary closure with resorbable sutures.

Contraindications

- Contraindications to coronectomy include:

- Teeth with active infection

- Mobile teeth

- Deep horizontal impactions as sectioning of the crown could in itself endanger the nerve 14.

Complications

Complications after coronectomy are rare but include

the following:

- Pain

- Infection

- Alveolar osteitis

Failed coronectomy i.e. mobilisation of the roots (9-38 per cent) - Inferior alveolar nerve injury

- Root migration (30 per cent) 14.

Post-operative pain is an expected complication but the more conservative nature of the coronectomy procedure results in less tissue disturbance and thus less post-operative pain than conventional surgical removal. Simple analgesia such as paracetamol and NSAIDs is adequate for post-operative pain relief in most patients 15.

The incidence of alveolar osteitis is 10 to 12 per cent. Should ‘dry socket’ occur, the management is similar to that in extractions of irrigation and placement of a dressing. Rates of infection after coronectomy range from 0.98 to 5.2 per cent. Local measures with antibiotics as an adjunct can be used to manage. If the retained root fragment is involved it may need to be retrieved, however, this is rare 15.

O’Riordan demonstrated in a study of 100 patients that the risk of infection was minimal and morbidity less after coronectomy than after surgical removal. Over the subsequent two years some roots migrated coronally and were removed under LA 16. Given the reduced risks of nerve injury, it has been recommended for patients where there is a high risk of nerve injury.

Root migration is estimated to occur in between 14 per cent and 81 per cent of cases. Pogrel estimates root migration of approximately 30 per cent over a six-month period 18. Similar results were found by Knutsson et al on a prospective trial of 33 patients where, after one year, all but six roots had migrated between 1 and 4mm 19. Migration can continue to the point where eruption into the oral cavity occurs. If this occurs, the roots will require retrieval but this is often at less risk than originally due to their migration away from the inferior alveolar nerve 15.

Conclusion

Inferior alveolar nerve injuries during third molar surgery can be reduced by:

- Thorough clinical assessment and decision making in line with guidance

- The use of appropriate imaging, including CBCT, to identify high-risk cases

- The use of the coronectomy technique where appropriate to prevent trauma to the inferior alveolar nerve.

Clinicians should consider coronectomy as an alternative to surgical removal for patients who are at a high risk of iatrogenic nerve injury.

References

- Management of unerupted and impacted third molar teeth. 1st ed. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; 2000.

- McArdle L, Renton T. The effects of NICE guidelines on the management of third molar teeth. Br Dent J. 2012;213(5):E8-E8.

- Howe GL, Poyton HG. Prevention of damage to the inferior dental nerve during the extraction of mandibular third molars. Br Dent J 1960; 109: 355–363.

- SDCEP Oral Health Assessment and Review Guidance – Published March 2011. Available from: www.sdcep.org.uk/published-guidance/oral-health-assessment

- Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposures) Regulations 2000 (IRMER). Available from: www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2000/1059/contents/made

- FGDP – Selection Criteria for Dental Radiography: Third Edition. Published 2015. Accessed 14/06/2015. Available from www.fgdp.org.uk/publications/selection-criteria-for-dental-radiography1.ashx

- Palma-Carrio C, Garcia-Mira B, Larrazabal-Moron C, Penarrocha-Diago M. Radiographic signs associated with inferior alveolar nerve damage following lower third molar extraction. Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 2010;:e886-e890.

- European Commission – Radiation Protection No. 172 Cone Beam CT for Dental and Maxillofacial Radiology (Evidence-based Guidelines). Published 2012. Available from: www.sedentexct.eu/files/radiation_protection_172.pdf

- Matzen L, Christensen J, Hintze H, Schou S, Wenzel A. Influence of cone beam CT on treatment plan before surgical intervention of mandibular third molars and impact of radiographic factors on deciding on coronectomy vs. surgical removal. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology. 2013;42(1):98870341-98870341.

- SIGN 43 – Management of Unerupted and Impacted Third Molar Teeth. Sign.ac.uk. Guidelines by topic. Available from: http://sign.ac.uk/guidelines/published/index.html#Dentistry

- NICE – Guidance on the Extraction of Wisdom Teeth. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta1

- Renton. T, Notes on Coronectomy. Br Dent J 2012; 212: 323-326

- Renton. T, Update on Coronectomy. A Safer Way to Remove High Risk Mandibular Third Molars Dent Update 2013; 40: 362–368

- Ahmed. C et al – Coronectomy of Third Molar: A Reduced Risk Technique for Inferior Alveolar Nerve Damage. Dent Update 2011; 38: 267–276

- Patel V, Gleeson C, Kwok J, Sproat C. Coronectomy practice. Paper 2: complications and long term management. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2013;51(4):347-352.

- O’Riordan B. Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997; 35: 209–212.

- Zola MB. Avoiding anaesthesia by root retention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992; 50: 419–421.

- Pogrel MA. Coronectomy to prevent damage to the inferior alveolar nerve. Alpha Omegan 2009; 102: 61–67.

- Knutsson K, Lysell L, Rohlin M. Postoperative status after partial removal of the mandibular third molar. Swed Dent J 1989; 13: 15–22.

About the authors

Michael Dhesi is a GDP at Clyde Dental Centre. He qualified in 2012 with BDS(Hons) from the University of Glasgow and has subsequently completed MFDS RCPS(Glasg) and an MSc in Advanced General Dental Practice at the University of Birmingham. Michael’s focus is in minimally invasive and adhesive restorative dentistry.

He also has interests in the management of dental anxiety and oral surgery and welcomes referrals in these areas.

Clive Schmulian qualified from Glasgow University in 1993. Throughout his time in general dental practice, he has developed his clinical skills by obtaining a range of postgraduate qualifications, which in turn led him to develop an interest in digital imaging in both surgical and restorative dentistry. He is a director of Clyde Munro.

CPD responses closed

The CPD quiz for this article is now closed. Please check the listings for the current quizzeslistings

Comments are closed here.