Lingual orthodontics – overcoming the hurdles

While advances in technology have provided the platform for clinicians to plan and produce incredibly precise orthodontic treatment, a thorough understanding of the principles and mechanics is still essential

There is rising interest in and demand for adult orthodontics in the UK. While much of this demand is met by the specialist orthodontist body, there are a number of techniques marketed to general dental practitioners as being more acceptable to adult patients.

Whether a clear aligner system or a “short term orthodontics” system with limited objectives, the principle aims of these systems seem to be trying to minimise the duration and cosmetic impact of treatment, while perhaps accepting that significant objectives, such as occlusal correction, root paralleling or torque control are sacrificed.

Lingual orthodontics has the potential to offer a truly aesthetic solution to both adult and adolescent orthodontic treatments, without making unnecessary compromises to the clinical outcomes. Surprisingly, the uptake in the UK remains marginal. In 2014, of 1,357 GDC registered specialists, approximately 750 had undergone training or certification in lingual appliance systems. However, less than one third of these trained specialists carried out any lingual treatments, with only around 3,000 cases treated annually. It would seem that there are significant barriers to patients being offered lingual treatment. This article aims to examine these barriers and see how they can be overcome.

Lingual appliances do result in slightly increased plaque and bleeding indices but these changes are completely reversible

Contemporary, fully customised, lingual appliances start with the end point in mind. There are many systems available. The most commonly-used system worldwide is Incognito (3M healthcare) developed by Dr Weichmann 1. After taking accurate silicone impressions or intra-oral scans, a physical or virtual set up of the idealised occlusion is produced. Following this, brackets are digitally designed to be as close fitting to the lingual tooth surface as possible.

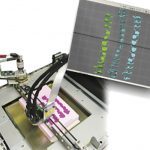

Wires are then custom bent by a 3D bending robot to connect the brackets that, when fully aligned, will precisely deliver the set up occlusion. Accurate bracket placement is crucial and indirect bonding trays must be used. Excellent precision of the final archwire to bracket contact is essential to ensure precise delivery of the setup (Fig 1).

Patient adaptation

Early lingual appliances, such as the Ormco 7th Generation (Fig 2) bracket were large and the indirect bonding customisation often resulted in significant protrusion from the lingual aspect of the tooth, encroaching upon tongue space. Patients would often report slow adaptation including difficulty with speech, tongue discomfort and eating 2. Over the last two decades, manufacturers have produced smaller brackets and the advent of fully customised systems that minimise both bracket and wire protrusion towards the tongue have greatly reduced these problems 3.

Dental health

It would seem logical that placing brackets lingually would complicate oral hygiene, increasing the risk of periodontal problems and caries. When periodontal health has been monitored, it has been shown that lingual appliances do result in slightly increased plaque and bleeding indices 4 but that these changes are completely reversible with no long-term increase in the presence of periodontal pathogens 5.

When the incidence of caries and white spot lesions has been examined, the results are surprising. Compared with labial appliances, lingual appliances result in 4.8 times fewer lesions, which, when present, show up to 10 times less intensity of decalcification 6. Therefore, there is in fact a compelling argument to use lingual appliances to reduce the risk of iatrogenic enamel damage compared with conventional labial appliances.

Outcomes

A possible barrier to the use of lingual appliances is the perception that clinical outcomes may not be as good as with labial appliances. Indeed, for any dentist to use a newer clinical approach, there is an ethical obligation to ensure that it will provide an outcome which is at least as good as that achieved by other proven, tried and tested appliances and techniques. There is evidence that well managed lingual appliances fulfil this requirement.

In a prospective comparison with matched labial and lingual cases, no difference was found in quality of outcomes, treatment time or apical root resorption between the two appliance groups 7. Further evidence on the potential accuracy of contemporary lingual appliances is in how closely treatment outcomes match the predicted set up occlusion. In a study where digital scans of the final occlusion were superimposed on the predicted setup, it was shown that 94 per cent of the planned movements were achieved 8. By comparison, the accuracy of Invisalign under similar investigations varied from 41 per cent to 59 per cent 9,10. It seems that lingual appliances have the potential to aesthetically deliver outcomes that are at least as good as those that we can achieve with conventional labial comprehensive orthodontic treatment.

- Figure 1a

- Figure 1b

- Figure 1c

- Figure 1d

- Figure 1e

Biomechanics

By applying forces to the lingual aspect of the teeth, the actions, reactions and moments are different to what we see with labial appliances. As the point of force application is distant from the labial surface of the tooth, we are effectively carrying out orthodontics at the end of a broom-handle! Accuracy and precision is essential. Finite element studies have shown that there is a greater tendency towards lingual tipping, vertical bowing of the occlusal planes and torque loss upon retraction 11,12. Various appliance modifications are made to counter these effects, such as optimal bracket and wire precision, close fit of bracket to tooth surface and ribbon-wise rather than edgewise archwires.

Technique sensitivity

This is perhaps the greatest hurdle to the widespread use of lingual appliances. The access to the lingual aspect of the teeth is certainly more difficult than with labial appliances or aligner systems. Contemporary brackets are small to ensure comfort and there is a lack of familiarity for the new lingual operator. The manufactures are aware of this issue and all systems are constantly evolving features and ligation techniques to make the life of a lingual orthodontist easier. It has been shown that self-ligating lingual brackets (Fig 3) will make life easier for the novice clinician, but that this benefit over a ligature-based system decreases as experience is gained 13. As with other fields of clinical practice, skills increase exponentially with experience and focused learning.

Digital planning

There has been much debate in the orthodontic world on where we should plan to position teeth. Decades of research and retrospective analysis have suggested that maintaining initial archform will minimise the risk of relapse 14. The introduction of novel treatment philosophies based on avoiding extractions 15 have optimistically hypothesised that there are no limits to where we can place teeth and that the alveolar bone will develop to accommodate any positions that we choose to place teeth.

However, met-analysis of clinical studies 16 and CBCT studies 17 have shown that the alveolus has limited adaptive potential. Basically, we must place the roots within the pre-treatment trough of alveolar bone if we are to maximise stability and minimise the risk of gingival recessions.

The digital planning platforms, such as 3M Treatment Management Portal or Sure Smile software allow the clinician to precisely plan where the final occlusion and tooth position will be, with reference to pre-treatment anatomy, considering aesthetics, stability and respecting constraints of the supporting tissues. With the precision of customised lingual appliances, we have the ability to accurately deliver the planned final occlusion (Fig 4), improving our treatment outcomes and potentially reducing iatrogenic effects.

As technology develops to allow better integration with CBCT and digital photography for aesthetic analysis, the clinician’s ability to plan and deliver optimal outcomes will continue to be enhanced.

Conclusions

There is a danger in hoping that technology or smart marketing can solve all of our clinical problems. For a clinician to become truly competent in a technique, he must be prepared to invest effort and time in becoming familiar with the principles, mechanics and effects of an appliance in both the educational and clinical settings. For those prepared to do so, the rewards for our patients are apparent. Carefully managed lingual appliances with digital planning platforms now provide the clinician with the tools to plan and precisely deliver optimal orthodontic treatment (Fig 5).

About the author

Robbie Lawson is a partner in Edinburgh Orthodontics, a specialist practice committed to achieving optimal outcomes for all patients. He did his dental training at Dundee University, graduating with honours in 1990. He undertook his orthodontic specialty programme at the University of Wales, graduating with distinction in 1996. He gained his Membership in Orthodontics from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, winning the William Houston gold medal. Since 1996, he has been in specialist practice in Edinburgh. He is past chairman of the Scottish Orthodontic Specialists Group, and is an examiner at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

He has had a special interest in lingual orthodontics since 1999, having used a wide range of lingual appliance systems over the years. He has published clinical and research papers and presents regularly nationally and internationally on fully customised aesthetic appliances. He is a member of the Worldwide Incognito Lingual Appliance Advisory Board.

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5a

- Figure 5b

- Figure 5c

- Figure 5d

- Figure 5e

- Figure 5f

- Figure 5g

- Figure 5h

- Figure 5i

- Figure 5j

- Figure 5k

- Figure 5l

- Figure 5m

- Figure 5n

References

1. Wiechmann D, Rummel V, Thalheim A, Simon JS, Wiechmann L. Customized brackets and archwires for lingual orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003 Nov;124(5):593-9

2. Caniklioglu C, Oztürk Y. Patient discomfort: a comparison between lingual and labial fixed appliances. Angle Orthod. 2005 Jan;75(1):86-91.

3. Hohoff A, Stamm T, Goder G, Sauerland C, Ehmer U, Seifert E. Comparison of 3 bonded lingual appliances by auditive analysis and subjective assessment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003 Dec;124(6):737-45.

4. Miethke RR, Vogt S. A comparison of the periodontal health of patients during treatment with the Invisalign system and with fixed orthodontic appliances. J Orofac Orthop. 2005 May;66(3):219-29.

5. Demling A, Demling C, Schwestka-Polly R, Stiesch M, Heuer W. Short-term influence of lingual orthodontic therapy on microbial parameters and periodontal status. A preliminary study. Angle Orthod. 2010 May;80(3):480-4. doi: 10.2319/061109-330.1.

6. Van der Veen MH, Attin R, Schwestka-Polly R, Wiechmann D. Caries outcomes after orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances: do lingual brackets make a difference? Eur J Oral Sci. 2010 Jun;118(3):298-303.

7. Deguchi T, Terao F, Aonuma T, Kataoka T, Sugawara Y, Yamashiro T, Takano-Yamamoto T.

Outcome assessment of lingual and labial appliances compared with cephalometric analysis, peer assessment rating, and objective grading system in Angle Class II extraction cases. Angle Orthod. 2015 May;85(3):400-7

8. Grauer D, Proffit WR. Accuracy in tooth positioning with a fully customized lingual orthodontic appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011 Sep;140(3):433-43.

9. Kravitz ND, Kusnoto B, BeGole E, Obrez A, Agran B. How well does Invisalign work? A prospective clinical study evaluating the efficacy of tooth movement with Invisalign.

Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009 Jan;135(1):27-35

10. Simon M, Keilig L, Schwarze J, Jung BA, Bourauel C. Treatment outcome and efficacy of an aligner technique–regarding incisor torque, premolar derotation and molar distalization. BMC Oral Health. 2014 Jun 11;14:68

11. Liang W, Rong Q, Lin J, Xu B. Torque control of the maxillary incisors in lingual and labial orthodontics: a 3-dimensional finite element analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009 Mar;135(3):316-22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.03.039.

12. Lombardo L, Stefanoni F, Mollica F, Laura A, Scuzzo G, Siciliani G. Three-dimensional finite-element analysis of a central lower incisor under labial and lingual loads.

Prog Orthod. 2012 Sep;13(2):154-6

13. Dalessandri D, Lazzaroni E, Migliorati M, Piancino MG, Tonni I, Bonetti S. Self-ligating fully customized lingual appliance and chair-time reduction: a typodont study followed by a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Orthod. 2013 Dec;35(6):758-65.

14. De la Cruz A1, Sampson P, Little RM, Artun J, Shapiro PA. Long-term changes in arch form after orthodontic treatment and retention. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995 May;107(5):518-30.

15. The Damon low-friction bracket: a biologically compatible straight-wire system.

Damon DH. J Clin Orthod. 1998 Nov;32(11):670-80.

16. Aziz, Flores. A systematic review of the association between appliance-induced labial movement of mandibular incisors and gingival recession. Aust Orthod J. 2011 May;27(1):33-9.

17. Cattaneo PM, Treccani M, Carlsson K, Thorgeirsson T, Myrda A, Cevidanes LH, Melsen B. Transversal maxillary dento-alveolar changes in patients treated with active and passive self-ligating brackets: a randomized clinical trial using CBCT-scans and digital models. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2011 Nov;14(4):222-33.

CPD responses closed

The CPD quiz for this article is now closed. Please check the listings for the current quizzeslistings

Comments are closed here.