Safeguarding vulnerable children

While not expected to make the decision to remove a child from an abusive carer, dental teams still have a crucial role in identifying and reporting potential incidences of abuse

The members of the dental team hold a unique position in the safeguarding of children. This article seeks to highlight the important role of each member of the dental team in the safeguarding of children and aims to ensure that passivity related to this issue will become a thing of the past.

Dentists and dental care professionals (DCPs) are not expected to make the often difficult decision to remove children from abusive carers, but should be confident in their professional responsibility to highlight and escalate concerns in an appropriate and timely manner. The importance placed on this professional duty is supported by the recent changes to recommended Continuing Professional Development (CPD) topics by the General Dental Council (GDC), with the addition of safeguarding children and young people added in April 2015.

The professional standards expected of every member of the dental team regarding safeguarding are clearly stated in the Standards for the Dental Team GDC guidance1 and highlighted below:

Standard 1.9

You must find out about laws and regulations that affect your work and follow them.

1.9.1 – You must find out about, and follow, laws and regulations affecting your work. This includes, but is not limited to, those relating to:

- data protection

- employment

- human rights and equality

- registration with other regulatory bodies.

Standard 8.5

You must take appropriate action if you have concerns about the possible abuse of children or vulnerable adults.

8.5.1 – You must raise any concerns you may have about the possible abuse or neglect of children or vulnerable adults.

You must know who to contact for further advice and how to refer concerns to an appropriate authority such as your local social services department.

8.5.2 – You must find out about local procedures for the protection of children and vulnerable adults. You must follow these procedures if you suspect that a child or vulnerable adult might be at risk because of abuse or neglect.

What is child abuse?

- The national guidance for child protection in Scotland 2010 describes abuse as “forms of maltreatment of a child”.2 This can be caused by significant harm directly to the child or failing to act to prevent this harm occurring. In this guidance there are four recognised types of abuse:

- Physical abuse: causing of significant physical harm to the child: examples are shaking, hitting, burning and choking.

- Emotional abuse: continued emotional neglect or ill treatment that has a detrimental and long-term adverse effect on a child’s emotional development. This can be caused by the child being made to fear their guardian, or feel worthless. In all types of child abuse, there will be an emotional factor attached.

- Sexual abuse: any child involved in any activity for the sexual gratification of another person. This is irrespective of whether it is claimed that the child has consented to the act. These activities can be physical or non physical, which includes using sexual language towards a child.

- Neglect: “persistent failure to meet a child’s basic physical and/or psychological needs, likely to result in the serious impairment of the child’s health or development”. This general neglect may result in the child being diagnosed with “non-organic failure to thrive”, meaning that the child has significantly failed to reach the normal weight, growth and development levels of those of similar age.

Child abuse is rarely inflicted on a child by a stranger, it is much more likely to occur by someone who is known to the child whether that is a direct relation or not. Radford, L et al (2011)3 states that over 90 per cent of sexually abused children were abused by someone they knew, and that one in 20 children have suffered from some kind of sexual abuse.

Dentists may be the only healthcare professionals that “at risk” children visit, so it is important that a thorough examination is carried out. Children are likely to have bumps and bruises, however the location of these injuries may make you suspect that there is a non-accidental cause. Dental trauma can also be a presentation of child abuse, so it is important to obtain a clear history of the incident from both the child and the parent.

Aspects to consider when carrying out this examination are:

- Do the child’s and parent’s stories match?

- Does the story change when being retold?

- Do the parent and child have a normal relationship?

- How is the child’s demeanour in the surgery?

- Do the injuries match the description of the incident?

- Is there a history of trauma?

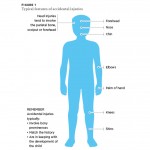

As dental professionals, we are not expected to diagnose these types of abuse, nor are we qualified to tackle such sensitive issues alone. This being said, we must be able to recognise patients who are at risk, look out for the signs of abuse and know when and with whom we should share our concerns. (Figs 1 and 2)

What is dental neglect?

The British Society of Paediatric Dentistry defines dental neglect as “the persistent failure to meet a child’s basic oral health needs, likely to result in serious impairment of a child’s oral or general health or development”.

Dental decay is a disease that is almost completely preventable yet, the most common cause for a child to be admitted to hospital is for tooth extraction under general anaesthetic (GA).4 There are numerous factors contributing to this issue and in isolation they should rarely raise suspicion about the care the child is under. The child’s general health, social-economic status and previous dental experience should all be considered when deciding if you have concerns for a child’s welfare.

Some features, which cause particular concern, are:

• Severe untreated dental disease, especially if it can be noticed by a non-dental health professional

• Disease that is significantly impacting upon the child

• Parents/carers that have access to treatment and dental care but persistently fail to obtain treatment for the child

• Repeated failed appointments

• Failing to complete treatment plans

• Only returning for emergency appointments

• Repeat GAs for dental extractions.

If a child’s dentition is neglected they may experience toothache, loss of sleep and have difficulty eating. They commonly have repeated courses of antibiotics, have only attended the dentist for emergency appointments and have had repeated GAs. All these factors increase the likelihood of the child to grow up having an overall negative perception of the dentist. These children are therefore more likely to be dentally anxious adults and continue the pattern of attending only for emergency care, which creates a vicious cycle for generations to come.

Dental neglect can be part of a wider problem in the child’s life and it is important to decide whether you need to raise your concerns. If, after repeated failed appointments to complete treatment and a discussion with the parents regarding your concerns you are still not satisfied, then you must share your concerns.

- Typical features of accidental injuries

- Typical features of non accidental injury

- The GIRFEC Wellbeing Wheel

- Child Protection and the Dental Team: Flowchart for action

What is the relevant legislation and how is this applied to dentistry? UN Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 5

This international treaty states that the best interests of the child should be a primary consideration and children should be protected from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury, abuse or neglect. The core values from the Convention underpin the ethos of all subsequent legislation regarding child protection.

Scottish Legislation

Legislation passed within Scotland is of most relevance to dental teams working in Scotland and are detailed here:

Children’s Act Scotland 1995 6

This act has incorporated key defining principles of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child into Scottish law. This act works to promote child welfare, preventing discrimination and ensuring ‘the voice of the child’ is heard.

Children and Young People Scotland Act 2014 7

This act is the legislative embodiment of the Scottish Government’s ambition for “Scotland to be the best place to grow up in by putting children and young people at the heart of planning and services”. The legislation from this act is currently in the process of being implemented through “Getting it Right for Every Child” (GIRFEC).8

The GIRFEC Wellbeing Wheel (Fig 3) shows eight areas of wellbeing, which if all are attained, should enable the child to grow and develop into a healthy and well rounded individual. It has also highlighted the need for an improvement in “joined up working” between agencies, education and healthcare. To facilitate this co-operation, two key roles have been identified, which are discussed below to help members of the dental team understand their roles and how to communicate effectively with these role-holders.

Who is the Named Person?

A Named Person should be appointed for every child in Scotland from birth until their 18th birthday or until they leave secondary education. The role will usually be given to someone already known to the family, for example the health visitor or a senior teacher. The Named Person should be used as a starting point for specific concerns. It could be useful for a general dental practitioner to make a record of a child’s Named Person, for example at their first appointment, in case contact regarding a concern is ever required.

The Named Person’s role is to act as a single point of contact, and to instigate further help, advice and support. They can support the family’s confidence to raise their personal concerns and to ensure the young person’s views are heard.

The infrastructure supporting the provision of Named Persons is currently being rolled out nationwide and may not yet be in place everywhere. We advise that you check locally regarding the stage of implementation that has been reached so far in your area.

Who is the Lead Professional?

When two or more agencies are involved in helping a child or young person, a Lead Professional will be appointed. The Lead Professional holds a number of responsibilities, from acting as the main point of contact, to promoting interagency working to supporting the child through crucial transitional stages.

This role is usually undertaken by a social worker. A dentist would not be expected to undertake the role of either a Named Person or a Lead Professional, but to simply consider contacting these individuals with concerns.

What is expected of me and what do I do if I have a concern?

The protocols for this scenario are clearly outlined in the flowchart in Figure 4, which has been taken from ‘Safeguarding Children and Young People: A Guide for the Dental Team’.9

The first concern should be to obtain as detailed a history and examination as possible, as these records may be relied on later as evidence. Negative findings as well as positive are important to record. Important questions to consider have been discussed earlier in this article. Regarding examination, it is important to examine the child thoroughly, noting any facial, oral or dental injuries. You should also appraise the overall appearance of the child: do they appear well cared for or are they “failing to thrive?” The child’s interaction with their carers can give insight into the presence or absence of abuse within the relationship.

You should always make it a priority to discuss any injuries with the child and allow them the opportunity to tell their story if they volunteer it. Do not ask leading questions and always take disclosures seriously. You should listen to the child in a non judgemental way and remain calm.

It is extremely important that you treat any injuries or symptoms appropriately, and the child should not be left in pain.

Your next consideration should be to discuss your findings with an experienced colleague to gain their insight into the situation.

If your concerns remain following this discussion, you should follow your local protocol by referring to your local social services department, the police, Area Child Protection Committee or equivalent. Referrals should be made by telephone, and should be followed up in writing within 48 hours. Ensure that the telephone conversation is documented in your clinical record, along with a clear action plan.

Best practice would indicate you should discuss your concerns with the parents and child, and inform them of your intention to escalate your concerns. Each case should be assessed individually, and it is reasonable to not disclose to the parents if you feel by doing so the child would be placed at greater risk or the referral would be unnecessarily delayed.

Comprehensive medical assessments (CMAs) are a common tool employed to compile evidence in suspected cases of child abuse/neglect. A paper published recently in the British Dental Journal10 explored the impact of dental input into CMAs conducted in Glasgow in recent years and clearly illustrates the importance of co-operation between different healthcare specialties. The two case studies described in this article are extremely useful learning tools. Common themes are revealed with regard to “at risk” children including multiple failed healthcare appointments, signs of dental neglect and the general appearance of the child. The case studies are an important opportunity to reflect upon your own clinical learning, including:

- Have I seen a patient with a similar presentation?

- Did I feel something was not quite right?

- Did I ask the right questions?

- Would I do anything differently the next time?

The dental practice as a whole can also reassess their practice policies with regard to safeguarding, and ask the question: “What measures have we put in place to ensure our paediatric patients are safe and healthy?” For example, policies regarding missed appointments should not punish or exclude the child patient, and patterns can become obvious more quickly if all the siblings of the same family are linked and their attendance patterns monitored as a unit.

Empowering the dentist and other DCPs to have the confidence to realise and utilise their role in safeguarding is paramount. General dental practitioners should be encouraged to discuss their concerns with colleagues within the practice and liaise with other healthcare professionals. For example, a telephone call to the patient’s general medical practitioner to ask their opinion on a patient’s unkempt appearance or uneasy interaction with their carer. Verbalising a concern does not automatically lead to social work involvement or a court case, but it is always better to be safe than sorry.

Conclusion

Recognising child abuse, in particular dental neglect, is an important part of dentistry and must be followed up in an appropriate manner to make sure that children do not slip through the care net. With new legislation coming into place in Scotland and the GDC recommending safeguarding of vulnerable children and young people as a CPD topic, dentists should understand their role in child protection.

As previously mentioned, dentists are not expected to make the diagnosis of child abuse, however they may be the only health professional a child is coming into contact with, so any relevant findings should be raised appropriately. Healthcare professionals should be moving away from assuming that someone else will voice concerns about a child, as this can allow a cycle of neglect or abuse to continue. The only way this can be achieved is by knowing when it is appropriate to seek help and by focusing on multidisciplinary communication and care for each vulnerable young person.

References

1. Standards for the Dental Team, GDC, 2013.

2. National Guidance for Child Protection in Scotland 2010. www.gov.scot

3. Radford, L.et al. Child abuse and neglect in the UK today. London: NSPCC. 2011.

4. C L Stevens. Is dental caries neglect? British Dental Journal. 2014; 217: 499-500.

5. UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, United Nations, November 1989.

6. Children’s (Scotland) Act 1995

7. Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014

8. GIFREC – Getting it Right for Every Child, Scottish Government publication

9. Harris J, Sidebotham P, Welbury R, Townsend R, Green M, Goodwin J, Franklin C. Child protection and the dental team: an introduction to safeguarding children in dental practice. Sheffield: Committee of Postgraduate Dental Deans and Directors (COPDEND) UK, 2006. www.cpdt.org.uk

10. C. M. Park, R. Welbury, J. Herbison & A. Cairns. Establishing comprehensive oral assessments for children with safeguarding concerns. British Dental Journal. 2015; 219: 231 – 236.

About the authors

Catherine McCann, BDS, MFDS(RCPSG). Core Trainee 2

Myles Gillespie, BDS. Core Trainee 1

Gillian C Glenroy, BDS, MFDS (RCPSG), MPaed Dent (RCSEd). Specialist Dental Officer- Paediatrics,

Public Dental Service, NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde.

Verifiable CPD Questions

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

- To gain an understanding of and be able to implement appropriate safeguarding practice for children and young people

- To review the legislation and requirements related to the safeguarding of children and young people in Scotland

- To further develop the dental team’s understanding of the principles of ‘getting it right for every child’ (GIRFEC) policy in Scotland

- To improve the dental team’s understanding of and ability to recognise child abuse and neglect

- To augment the dental team’s understanding of, and ability to recognise, dental neglect

- To further develop the dental team’s understanding of, and ability

- to respond to, a concern about child abuse and neglect.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

- The dental team should be aware of the latest legislation related to safeguarding of children in Scotland

- The dental team should be able to describe the principles of GIRFEC in relation to safe guarding children

- The dental team should be able to identify a child at risk of/or experiencing neglect or abuse and take appropriate actions.

Comments are closed here.